“But you don’t look gay”—icons and representation

Cara Sullivan delves into the problematic relationship between queerness and appearance, the expectations and prejudices that come with our ideas of (homo)sexuality. In this article, she turns towards the gay icons that gave people a fashion voice.

On the 13th of July, 1985, Freddie Mercury stepped onstage before a televised audience of 1.9 billion people. You’re probably familiar with what he was wearing: a simple vest, light-wash denim jeans and a silver amulet on his left bicep.

The look has since become his most iconic, surpassing his harlequin leotard and soap-opera inspired drag in the “I Want to Break Free” music video as a favourite amongst cosplayers. It may seem like Mercury is resisting the femininity of his earlier looks—namely the glam-rock of the 1970s—and embracing his more masculine side, but his Live Aid attire is far more subversive than costume jewellery and platform shoes; it embraces an aesthetic that was exclusively and unapologetically queer.

Developing in the late 70s, the “Castro-clone” became a staple of the gay scene. The look was inspired by icons of masculinity, particularly traditional working-class men: plaid shirts, form-fitting tees, shrink-to-fit denim trousers, moustaches and sideburns was à la mode in queer circles. The look was innocuous and appropriate for non-queer venues, but carried a powerful subtext. While it is unlikely that Mercury was attempting to make a political statement with his choice of dress, he was still performing his sexuality in a way that other gay men would recognise and relate to, whilst simultaneously flying under most straight people’s radars.

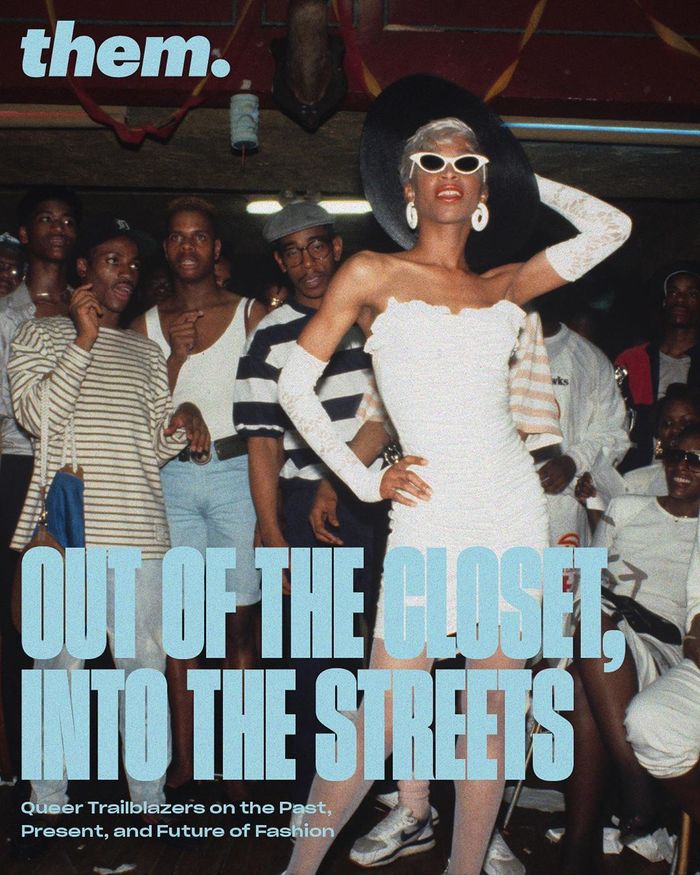

Mercury embracing the fashion of queer nightlife, wearing it before a crowd of millions in a non-queer space and elevating it to icon status says something about the power of fashion as a transgressive paralanguage. Relevant also is the fact that the “Castro-clone” was conceived in the gay nightclub scene, a domain that not everyone will have access to. In an urbanised space like Manchester, which boasts a vibrant gay community, it’s easy to see how and where these trends spread and garner associations; it would seem that queer people dress in a certain way because of osmosis. But what about places that have little to no queer spaces?

"I’ve always done it, but it could have been backed up in my subconscious by social media"

I spoke with Kai, a twenty-year-old non-binary person from Farnham, a market town in Surrey. “The demographic here is middle-aged, middle-class white people,” they say. “I never saw anyone who looked like me when I was at secondary school. When I was younger walking around, I noticed I’d get a lot of stares.” Despite only coming out in their mid-teens, Kai noticed the roots of their identity before they were old enough to understand it. “At school I used to hate having to tie my school cardigan around my waist—I saw all the girls doing it and for some reason I hated doing it. It was so inherently girly.”

Non-binary representation in particular is rare and seems to be more ubiquitous on social media platforms than anywhere else. Even then it is whitewashed and homogenous: “The stereotypical non-binary person within pop-culture is an androgynous, male-presenting skinny white person, which is weird because I feel like I do fall into that somewhat.” Despite growing up with a lack of NB representation, Kai claims to have discovered their style organically. “I’ve always been quite ‘gender neutral’ in the way that I dress. I have never gone out of my way to change this, I’ve always just worn what I like wearing—but what I like wearing is incidentally what a lot of people would think of as the norm for non-binary people; I’ve always done it, but it could have been backed up in my subconscious by social media.”

For someone with an identity as scarcely understood by the mainstream as Kai’s, it makes sense that they would gravitate towards people like them, and in turn, their style. Whilst adolescence is a time of self-discovery for all of us, queer people’s experiences tend to be particularly complex. Being expected to “come out” not only imposes a pressure that straight people don’t have to face, but makes it necessary to have a resolute and fully-realised attitude towards your sense of self. With this forced cognisance of identity, it’s no wonder that queer people are sensitive to how others perceive them; we may all desire to find our place in a community, but for queer people, the LGBT community may be the only place where they feel safe and seen.

Despite this long and proud history of queer transparency, it’s important to remember that fashion and expression don’t hinge on sexuality. Just as it is no-one’s right to define how “queer” looks, it’s also no-one’s business to decide whether or not you fall into their idea of queerness. The infuriating assertion: “But you don’t look gay” can take on many different forms: it can be the straight girl from secondary school who still thinks that “gay” is an insult and wants to give you a backhanded compliment (ironic as she was one of the people who mocked your ugly year 8 pixie cut by saying it made you look like a “lesbian dinner lady”.) It could also be a gatekeeping queer person within a safe queer space. People in the LGBT community aren’t without flaws, and some might read your lack of out-and-proud-rainbow-wearing gayness as a kind of resistance, denial or shame.

I love fashion. I use it to express myself in a way that makes me feel comfortable and confident, not as a shorthand to tell the world who I prefer to sleep with. Whether we want to advertise our sexuality to others or not, one thing is absolutely crucial to self-expression: choice. Dressing femme, butch, subtle or extravagant is your choice, and does not invalidate your identity as a queer person.

And if you suspect that someone might be queer because of the way they dress, there’s only one way to find out: by asking.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026