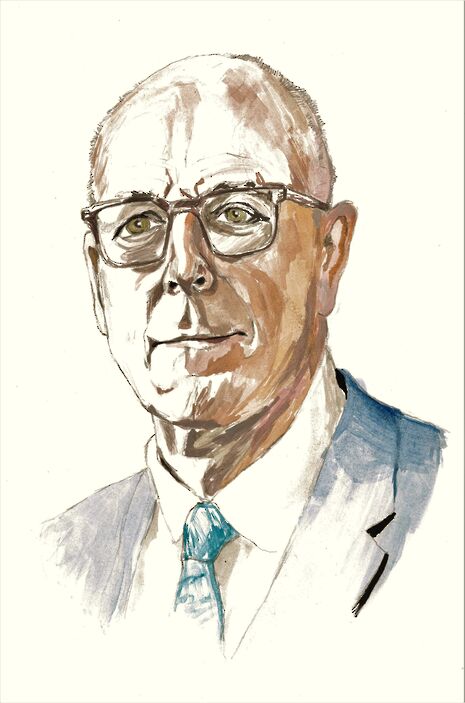

Dylan Jones on what it means to be GQ editor in a post-truth world

Julia Davies interviews the editor of GQ Dylan Jones who talks about the survival of the publication in the face of the digital age, #MeToo and the “more fragmented and fragile” media industry

“I think the most important thing for us is the fact that we’re still here.”

Dylan Jones’ judgement on GQ’s 30th birthday may come as a shock to anyone looking at this deeply self-assured magazine. The thought of this publication succumbing to the fate which has befallen industry titans such as The Face in the past few decades seems laughable. That Jones is proud at the mere survival of GQ is a salutary reminder of the precarious times facing journalism.

Jones has been editor of GQ for 19 years, during which the industry has changed beyond recognition. “The biggest change is in terms of technological change,” he says, referring to distribution and consumption behaviours. But there is a more worrying change in attitude that he also notes. “There is a presumption, particularly amongst [millenials], that news and content is not something you have to pay for.” The idea that everything should be free and instantly available, but also of top journalistic quality, reflects for Jones a “belligerence” amongst consumers operating in an “accelerated culture”, and is the greatest danger facing journalism today. This reluctance to pay for articles is the biggest difference between our generation and its forebears. GQ’s app is an important part of its future growth plan.

I don’t see any contradiction in having an advertisement for a pair of shoes next to a tremendous piece of journalism. One pays the other.

But this cutting-edge focus on the future seems at odds with the title of the magazine, Gentlemen’s Quarterly. I put this to Jones and he pauses for thought. “I think the relationship between the brand and the words is so abstract that they’re almost meaningless.” This is not mere bluster, however. In the light of #MeToo and other social movements, the 30th anniversary of GQ has not been marked with lavish shoots, spectacle and ‘banging our chest’, but instead by an in-depth YouGov study called ‘The State of Men’. The study attempts to find out how men feel in and about themselves, their partners and their well-being in general.

For Jones, the author of 2006’s consciously tongue-in-cheek Mr Jones’ Rules for the Modern Man, now is not a time for jocularity. Instead, it is more important than ever to be a ‘gentleman’ - a word which to Jones simply means “being a good man.” Now is an opportune time to retrospect, and it is clear that culture has changed beyond recognition since 1988, when the magazine was launched. “It’s like different centuries. Everything is different. Twenty years ago, if I’d put a man on the cover, I’d have lost my job in six months, because it wouldn’t sell”, asserts Jones. To date, GQ has featured Sadiq Khan twice, and Jeremy Corbyn and David Cameron, amongst other high profile figures. “Culture has changed almost 180 degrees since the 90s, and for the better.”

At one stage I refer to GQ and similar magazines as ‘glossies’, and Jones slams his glass on the table. “That was disparaging.” The idea, to Jones, that luxury goods or fashion are a form of dilettantism is “puerile” and “demeaning”. To him it seems akin to saying “you can’t watch colour films”.

But surely he must have encountered this opinion before? “I love that world [of magazines], it’s intoxicating. I don’t see any contradiction in having an advertisement for a pair of shoes next to a tremendous piece of journalism. One pays the other.” The fashion industry “makes more money than the car industry.” He is tired of people thinking it’s cool to know nothing about fashion, a view he sees as “incredibly sexist.”

Media has changed enormously: the media industry is more fragmented and fragile than it used to be

He is similarly incensed by the idea that he would be taken less seriously for fusing fashion and politics if he were female. “Why would anyone think that?” he exclaims. He lists Rosie Boycott and Tina Brown as formidable female editors from the 1960s onwards, who brought profound changes to the industry and are still viewed as authoritative today. “It ceased to matter. I think that’s an odd question.”

He is tired of tabloid-style scrutiny of what people wear, such as Theresa May’s ‘trousergate’, but he is sanguine about the realities facing publications today. “If Vogue sold six times more copies a month, would it still be Vogue? You’d have to alter the editorial to appeal to that many people. We can’t compete with Google. How could we? We don’t have that scale. We have to deliver a very particular audience for our advertisers. It’s all about demographics.” Jones emphasises the scale of the competition facing publications like GQ. “Media has changed enormously: the culture, delivery systems… people are far more judgemental these days. The media industry is more fragmented and fragile than it used to be.”

What can we predict of GQ’s 40th anniversary? “The aspirations of the publication will remain the same, but in what form it’s delivered, I have no idea. All people buy into us for our taste.” In Jones’ eyes, the role of GQ is to provide “nuance” and “filtering” in the face of the internet, which is a “mass of stuff”. GQ’s commitment to quality has never wavered, even when the society its readers inhabit, such as during what Jones calls the “fag end of the 90s, the Brit-pop era”, was not so highbrow.

Jones has no desire to play to the gallery, though. When asked if he feels he has to tread a middle path to appeal to as many readers as possible, he is horrified by the notion. “We don’t have to do anything!” he exclaims.

Jones reiterates his fears surrounding the devaluation of journalism, and the assumption that people are “just content providers; that it doesn’t mean anything any more.” He sees this putting talented people off becoming journalists: it sets a worrying precedent. “However, there is beginning to be a return to an appreciation of expertise. I hope I’m right.” When we are faced with so much news, some of which is not fact-checked or even true, people are returning to the sources and interpreters that they can trust. In the wake of Trump, and Brexit, argues Jones, people are seeking a greater degree of engagement. It’s becoming a conversation. Perhaps it is this understanding of the interplay of fashion, politics and society that means that GQ is still here.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026