Escaping the frame: the art of hairballs

Jade Cuttle explores the work of Mona Hatoum, an artist whose hair-based work evokes praise and disgust in equal measure

Hatoum’s exhibitions are easily a worst nightmare. Strands of human hair suspended from the ceiling stroke the skin of the unsuspecting spectator, elsewhere they are woven on a wooden loom, scattered across the floor in balls or beaded into a beautiful necklace. It can be difficult to see beyond the blatant horror of hair, particularly if you're one of those people for whom a blocked plughole brings on panic attacks, your heartbeats chasing after each other at the trace of its touch. However, the works of Mona Hatoum, a Lebanese-born Palestinian award-winning installation artist who has been exhibiting around the world since 1983, are considered to be masterpieces of contemporary art for many reasons.

I’ve been hoarding my own hairballs ever since I first saw her work a few months back at the Pompidou Museum in Paris: I haven’t thrown away a single strand. This habit was initially proclaimed to my parents under the pretext of making my own hair extensions, being a cheaper and somehow more convincing alternative. In the end it just made a matted mess, at which point I was confronted with the choice to either throw them away or to keep on hoarding. I had no idea what to do with it all, other than to weave a scarf to keep me warm through the winter. In any case, this strange dilemma was when the extent to which my subconscious had been startled by a beauty to which we are typically blind dawned on me.

At first glance, Hatoum exposes the complex relationship we have with our bodies, as the beauty of hair turns to disgust as soon as it is detached. There is an ever-deepening sea of self-questioning in our society, dropping its anchor with significant force on the subject of female hair. To shave or not to shave in shape with the media-imposed ideals that modulate our existence: is that part of her artistic question?

If we dwell on the semantics of the title Recollection, we see that the concept of memory is crucial. It is as though the strands of time, as well as hair, have slipped from the artist's hand, each loosely missing the needle's eye. In other words, not only does this artwork escape from the traditional frame of artistic representation, but due to its texture, it also escapes from the frame of time. Owing to its slow rate of decomposition, there is a hint of the eternal in hair, or of something more than the ephemeral: detached strands are undeniably dead yet defiantly still alive.

If we delve a little deeper, we see that she explores in equal measure the concept of space as sculpture. The traditional boundaries between private and public, artist and beholder are transgressed with a violence so strong that the pictures shiver and shake in their little plastic frames on the floor below. After a six year long harvest, the hair is the artist’s own. And so when the most daring strands dip their toes into a tourist's all too gaping mouth, nothing could be more intimate or invasive.

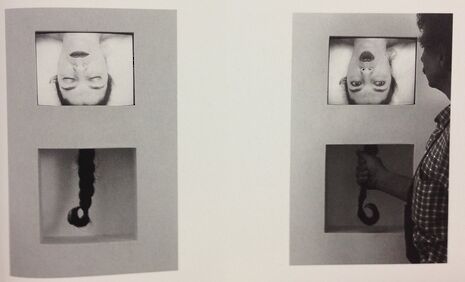

This transgression is particularly true of her three day performance entitled Pull (1995), where a handful of hair was offered to each visitor, causing pain to flicker across a face on a TV screen as it was pulled. The TV screen turned out to be an illusion, as it was the real hair and pain of Mona Hatoum herself.

The hallmark of her work is a fascination that follows in the footsteps of avant-garde surrealism and some of its striking juxtapositions. The most famous example is Object (1936) by Meren Oppenheim, a sculpture consisting of a teacup, saucer and spoon all covered with fur from a Chinese gazelle. In piercing parallel with such surrealism, the visual frame of expectation here cracks at the corners and crumbles. Surely hair should be tossed in the bin, not toasted by critics clinking little glasses of champagne in an art gallery? Perhaps, but Mona Hatoum is a cutting-edge contemporary artist who refuses to work within a wooden frame.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025

Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025