Brydon: Prejudiced?

meets award-winning comedian and Keith Barret alter-ego to discuss panel show pride, self mockery and how he’s finally managed to reconnect with his Welsh roots

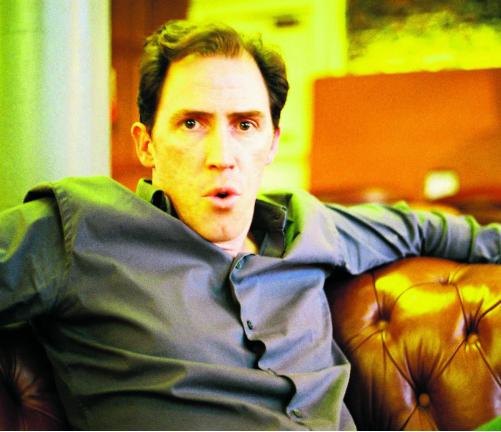

Half w ay through my interview with Rob Brydon in a private members’ club off Shaftesbury Avenue, a group of loud and ostensibly obnoxious media types storm into the obviously closed off area. He leans in closer to the table and lowers his voice, distracted, and makes a strained face at his publicist, trying in vain to catch her attention. There is a more than subtle resemblance to his absurdly straight-lined alter-ego, divorced cabbie Keith Barret, shocked by the vulgarity of his celebrity guest. His first manifestation on television as Barret, the focus of the BAFTA nominated Marion and Geoff (produced by Steve Coogan’s Baby Cow production company), encapsulated the ambivalent darkness of much of his previous work, including the seminal Human Remains with Julia Davis. I was keen to find out why he eschewed this in favour of the light-hearted Keith Barret Show concept – in Brydon’s own words changing “beautifully crafted monologues” into, superficially at least, easy pickings. “I am drawn to a sort of bleakness in comedy, but the Keith Barret show was s a satire on light entertainment. People can walk straight off from Big Brother into these chat shows, so why not a divorced taxi driver? Why not Keith?” On closer inspection, however, even in his less demanding format, Brydon’s Barret is an impossibly incisive and quick-witted character.

ay through my interview with Rob Brydon in a private members’ club off Shaftesbury Avenue, a group of loud and ostensibly obnoxious media types storm into the obviously closed off area. He leans in closer to the table and lowers his voice, distracted, and makes a strained face at his publicist, trying in vain to catch her attention. There is a more than subtle resemblance to his absurdly straight-lined alter-ego, divorced cabbie Keith Barret, shocked by the vulgarity of his celebrity guest. His first manifestation on television as Barret, the focus of the BAFTA nominated Marion and Geoff (produced by Steve Coogan’s Baby Cow production company), encapsulated the ambivalent darkness of much of his previous work, including the seminal Human Remains with Julia Davis. I was keen to find out why he eschewed this in favour of the light-hearted Keith Barret Show concept – in Brydon’s own words changing “beautifully crafted monologues” into, superficially at least, easy pickings. “I am drawn to a sort of bleakness in comedy, but the Keith Barret show was s a satire on light entertainment. People can walk straight off from Big Brother into these chat shows, so why not a divorced taxi driver? Why not Keith?” On closer inspection, however, even in his less demanding format, Brydon’s Barret is an impossibly incisive and quick-witted character.

The Keith Barret Show, along with his recent Annually Retentive, a pastiche of the panel-show format complete with behind-the-scenes bitching and devising, both gleefully take the piss out of B-list and C-list celebrities, but Brydon insists that this is all in good nature. “I’m very fond of Richard and Judy, the guests on the Keith Barret pilot. Some of the guests on these shows understand it. You want to be captain of the ship but you’re not - you’re the cabin boy. Lembit Opik didn’t want to play the game and Eamonn [Holmes] did.” The success of these shows comes in no small part from the fact that Brydon is often on the panel himself, though he admits he “only picks the good ones”.

One of these is surely the Big Fat Quiz of the Year, which Brydon has returned to for the past four years on the trot. I’m interested to know the degree of preparation involved in something like this, but he assures me it’s kept to a minimum. So which guests do the best? “It’s Russell [Brand] and Noel [Fielding]’s show, really. You’ve got to assume roles on these shows, and Dave [Walliams] and I play it as the straight guys. I can’t compete with their stream of consciousness. I don’t do gigs. I’ve never taken a drug in my life. I’m married! But you’ve got to be on your toes because I watch these things as a fan and I say to my wife, ‘we haven’t heard much from him this evening have we?’” I put it to him that Fielding often stumbles through these shows with a permanent vacuous spastic grin, entirely unable to pull out a single funny quip or comment, but Brydon is admirably unwilling to put down any of his costars, and comes to his defence quickly. “Comedy is so much about attitude – look at Woody Allen or Russell Brand. Once you have that attitude everything is easier, but getting it is not easy.”

He has recently branched away from pure comedy, playing roles in shows such as Napoleon and Gavin and Stacey, which took away a clutch of prizes from the British Comedy Awards last year, and is soon to start its second series. “Comedians have a certain way of looking at the world, close to filtering life.” He’s keen to stress the more difficult, studied approach he takes to straight acting. “You’re constantly thinking, ‘Where can I give a good reaction shot to keep me in the scene?’. You want to win every scene. Not in that way – god, that sounds horrible. You’re not going to print that are you? I bet you are.”I assure him that I won’t. The underlying modesty he shows seems to be in harmony with much of his work – he chooses his projects incredibly carefully. One of them was the marvellous Cock and Bull Story, a big screen interpretation of Lawrence Sterne’s ‘unfilmable’ The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, arguably driven by the constant quibbling between Brydon and Steve Coogan, both playing versions of themselves. “The banter on camera is an edgier, loveless version of what we really are. The only improvised bits were the sections that book-end the film – the bit about the teeth [Brydon is accused of havingat the start and the Al Pacino impressions at the end. I always turn to Al.” I ask him whether his pride takes a bashing at all when he mocks himself on screen – after all, much of Keith Barret was ultimately tragic, and there are plenty of personal snipes in Cock and Bull (“Have a look at the colour,” he says in the intro, tapping his teeth. “It’s what I call not-white. Actually it’s a nice colour – I think you could decorate a child’s nursery with this colour.”) He starts out with an utter Barret-ism. “You’re what I call a young person, but as you get a bit older and more comfortable in your skin, you’ll do pretty much anything for a laugh. After all, your life isn’t what goes on screen. That’s your job, your work. I wouldn’t bring my career if I was evacuating the planet – I’d bring my family. “

His newest project is a documentary, and the decision came easily to him. “I wanted to do a documentary on things I have a passion for. Not Elvis Presley, that’s been done to death. Then I thought of Wales - it stemmed from the seed of dismissiveness in the character in Annually Retentive. So I booked a theatre in Aberdare for a stand up show – as myself, not Keith.”The premise of a booked stand-up show galvanised him into getting the documentary on track, as well as the desire to appease a friend jaded by constant (albeit fond) Welsh-bashing. When he toured as Barret, an exchange with an audience member epitomises this attitude: “Do you speak Welsh? You do? [a pause] Why? No, no, no- what I mean is, is it part of your job, or were you forced to learn it as a child?”

The gloomy Welsh attitude is summed up by Brydon’s meeting with Manics’ bassist Nicky Wire. “He told me that after If You Tolerate This went to number one, they were all delighted for 20 minutes; but after that they were gloomy again, on the tour bus, because it had sold 20,000 fewer copies than they expected.”But the show works. Some (wisely edited) stand up at the start shows his anti Welsh humour bombing, but as he turns the focus round to his favoured self-mocking, the audience at the show’s end empathises and is utterly won over. “I feel like I’ve rediscovered a part of me, and a part of my country. I was living here in London in my lovely media world with my friends, and I felt quite disconnected. But when I drove back, and heard the Welsh accent of the girl in the toll both on the Severn Bridge, it made me feel warm inside.”

Comment / Not all state schools are made equal 26 May 2025

Comment / Not all state schools are made equal 26 May 2025 News / Uni may allow resits for first time24 May 2025

News / Uni may allow resits for first time24 May 2025 Fashion / Degree-influenced dressing25 May 2025

Fashion / Degree-influenced dressing25 May 2025 News / Clare fellow reveals details of assault in central Cambridge26 May 2025

News / Clare fellow reveals details of assault in central Cambridge26 May 2025 News / Students clash with right-wing activist Charlie Kirk at Union20 May 2025

News / Students clash with right-wing activist Charlie Kirk at Union20 May 2025