‘I spend every day drawing people I hate’

shares a pint with Guardian cartoonist , the country’s most vicious satirist

As the cartoonist Martin Rowson buys me a pint at the University Arms I admit that I’ve already been to the pub today, and I hope I don’t get pissed. He tells me when he was an undergraduate at Cambridge and just about to interview someone himself, a mate left some weed in his pigeon hole, and obviously, as it would have been impolite not to try it, he smoked a bit before he left, and inevitably couldn’t remember much of what followed. I felt trumped.

Martin Rowson describes himself as a visual journalist, but he’s more; he’s a very vicious and visceral visual journalist. His political cartoons can be scathing, bloody, cruel and scatological – and also very funny. He says proudly that many found his take on Blair the most unpleasant, and he’s currently trying to do the same with Cameron by depicting him as Little Lord Fauntleroy. He contributes regularly to the Guardian, Time Out, the Scotsman and the Mirror, as well as having published a number of books including a novel, a memoir and some graphic novels. “The point of political cartoons”, he tells me, sitting at a table overlooking Parker’s Piece, “is they’re a kind of voodoo. The point is to do damage from a distance with a sharp object – in this case a pencil or a pen”, and to illustrate this he whips out a pen and brandishes it menacingly. Sometimes politicians buy his drawings and hang them in the loo, attempting to “diffuse the bad magic by flushing it down with the shit.” His book Mugshots is a compilation of 60 caricatures of leading political figures drawn over lunch at the Gay Hussar. Charles Clarke was a “joy to draw…fatty big ears!” Alistair Campbell sat scowling cross-armed, before finally shouting across the restaurant “you just won’t be able to stop yourself making me look like a really bad person!” Rowson replied, “Alistair, I draw what I see.” But later he admits he actually quite likes Campbell, perhaps because he once complimented him “you’re the only one of these c*nts who can actually draw me.”

Martin Rowson describes himself as a visual journalist, but he’s more; he’s a very vicious and visceral visual journalist. His political cartoons can be scathing, bloody, cruel and scatological – and also very funny. He says proudly that many found his take on Blair the most unpleasant, and he’s currently trying to do the same with Cameron by depicting him as Little Lord Fauntleroy. He contributes regularly to the Guardian, Time Out, the Scotsman and the Mirror, as well as having published a number of books including a novel, a memoir and some graphic novels. “The point of political cartoons”, he tells me, sitting at a table overlooking Parker’s Piece, “is they’re a kind of voodoo. The point is to do damage from a distance with a sharp object – in this case a pencil or a pen”, and to illustrate this he whips out a pen and brandishes it menacingly. Sometimes politicians buy his drawings and hang them in the loo, attempting to “diffuse the bad magic by flushing it down with the shit.” His book Mugshots is a compilation of 60 caricatures of leading political figures drawn over lunch at the Gay Hussar. Charles Clarke was a “joy to draw…fatty big ears!” Alistair Campbell sat scowling cross-armed, before finally shouting across the restaurant “you just won’t be able to stop yourself making me look like a really bad person!” Rowson replied, “Alistair, I draw what I see.” But later he admits he actually quite likes Campbell, perhaps because he once complimented him “you’re the only one of these c*nts who can actually draw me.”

This picture of politics is not a pleasant one. It is bitchy and cruel and the damage from the pen seems to be partly a stab in the back. Although he reluctantly votes Labour, Rowson is adamant the role of political cartoonists is always to be oppositionist and that it’s healthy for politicians to be depicted as the “liars, knaves and fools” they are. But does he ever feel some sort of moral obligation? “The purpose of satire is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortless. It is the job of the satirist to point out the idiocies, absurdities, wickedness and immorality of the people in charge… allow the led to laugh at the leaders, to think this man is an imbecile or he’s just got a big nose.” His cartoons are cruel and perceptive visual rants which continue the tradition of the eighteenth-century caricaturist Gillray, who set the template for what Rowson and Steve Bell are doing now, appropriating and transforming recognizable figures. But he feels that cartoonists get a bad press. Cartoons are strange – they are “the mutant child of text and image” – and cartoonists “should actually be somewhat excluded, treated as though we’re not quite decent, because what we’re doing is visual bugging, being vicious and unpleasant and not quite the sort of person you’d invite round for dinner because we’d probably throw up on your food.”

It seems that for Rowson, what he does with the subject is more important than what he does with the image. “I’m not particularly interested in art,” he states nonchalantly as I almost spit out my Grolsch in shock. “Well,” he corrects himself, “not that interested in doing art.” He has no formal art training and, although he knew since he was ten that he wanted to be a cartoonist, he never thought an art school could teach him how to be one. Instead he read English at Cambridge. It was the late 70s: the “winter of discontent”. I probe him to reveal some Cantabridgian adventures. “What japes I got up to?! Christ Almighty!” I sit forward on my chair in anticipation, but what he tells me is actually quite sad. He remembers it as “cold and miserable and dirty; everything falling to pieces.” Once, when Andrew Marr (then an intense lefty with a Trotsky goatie), came canvassing for CUSU at Rowson’s college, the boat club threw him in the pond, and Rowson proudly remembers out-singing the Rugby boys at the bar with revolutionary songs.

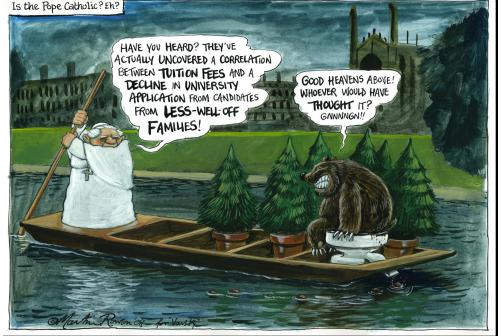

Maybe the reason Rowson’s Cambridge experience was so bleak is because he drew for Varsity’s rival paper ‘Broadsheet’. He has since seen the error of his ways, and this week has very generously drawn the Varsity editorial cartoon. Flick to page 11 to see his inspired take on Cambridge life. I ask him about his process. This one was drawn in pencil, gone over with Pelican Indian ink (the same as the Nazis used for tattooing people in concentration camps – slightly creepy), then all painted over with a gouche mixed up wash of burnt umber and Prussian blue before picking out details by highlighting. “Cartoons are very complicated in how they work and what they do; it should look like a fight between the cartoonist and the paper.” Rowson used to buy his nibs from the same man that Ralph Steadman bought his from. And this old man thought it scandalous, the way “Ralph uses the nibs like chisels”, but Rowson happens to think “it’s incredibly sexy”. In terms of what comes first – text or image – it’s a marriage of the two. He listens to the radio all day, hoping at some point to get a flash of inspiration. “The discipline of a deadline is great for concentrating the mind; a strange kind of terror pumps the adrenaline.” He’s lucky that he gets complete editorial freedom at the Guardian. The only thing the editor Alan Rusbridger doesn’t like is “shit…actual shit.” But Varsity isn’t so fastidious.

Rowson’s appropriation of recognizable figures transcends the political world, into the literary. His graphic novel of Tristram Shandy was “a labour of love”, and aimed to “take the piss out of the academic response” to a book rarely read but often called a classic. The purpose of Rowson’s take on The Wasteland, however, was to mock the poem itself. He transformed it into an incomprehensible film noir nightmare of exciting, if exhausting, details. Eliot’s poem is apparently a “terribly turgid, bloody behemoth of Modernism… I can’t stand it.” I’m a little too scared to voice outright opposition and only wonder why he spent a year on something he hates. “I spend every day drawing people I hate.” Fair enough.

As our drinks become dregs I ask him one last question, downing my glass to give me confidence: would you say you’re quite angry? “No, I’m just as pissed off as everybody about most things. My current feeling about politics is boredom. But then the one thing which would be really bad for me is if everything suddenly became wonderful. A world of universal happiness would be incredible dull and I’d be out of a job.” As we leave he tells me about his new book, out in October. It’s called Fuck: A World Odyssey. There are 67 full colour pictures of life on Earth, each containing the word “fuck”. His arms become animated as he grins “so you have the big bang – ‘fuck!’, creatures crawling out of the Earth going ‘fuuuuck!’ I think it’s quite nice. It’ll be interesting to see if it gets stocked in W H Smith’s. But the publishers are happy with it.” I bet they are.

News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025

News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025 Comment / A plague on your new-build houses18 August 2025

Comment / A plague on your new-build houses18 August 2025 News / Trinity sells O2 Arena lease for £90m12 August 2025

News / Trinity sells O2 Arena lease for £90m12 August 2025 News / Pro-Palestine activists spray-paint Barclays Eagle Labs18 August 2025

News / Pro-Palestine activists spray-paint Barclays Eagle Labs18 August 2025 News / Uni welcomes new students14 August 2025

News / Uni welcomes new students14 August 2025