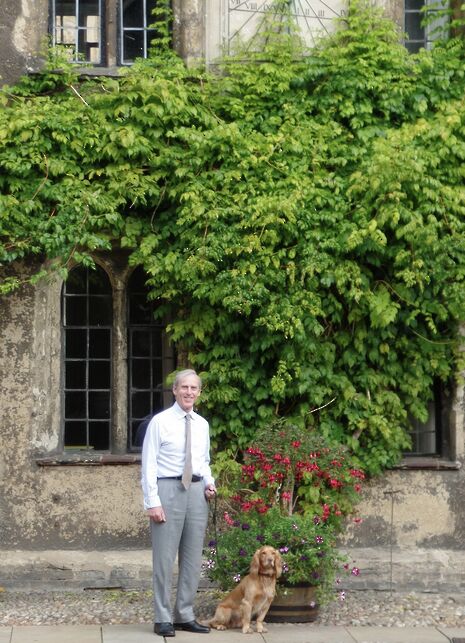

Stuart Laing: the Velvet Revolution to Corpus Christi

Kenza Bryan talks to the Master of Corpus Christi about the Foreign Office, Cambridge and – reluctantly – the Farage Formal.

Stuart Laing studied Classics at Corpus Christi College and has been Master there since 2008. He entered the Foreign Office after graduation in 1970, serving as a diplomat in Czechoslovakia and the Middle East from 1989 to 2008.

Stuart Laing is a real fount of knowledge on the history of Cambridge, the kind of person who can pluck anecdotes out of thin air and weave them into conversation with a knowing grin. On what Corpus was like without women however, he is surprisingly demure. “We did a few laddish things as young men do.” But even the notorious Chess Club “didn’t get up to the really naughty high jinks that happened thereafter.”

When I ask how assiduous his lecture attendance was, he brings up his 2:1.“If it doesn’t sound too pompous to say, it was a fairly conscious decision. I was going to play sport, I was going to make friends, I was going to do a bit of music and the result of that was that I didn’t give the attention to the classical philosophy.”

Extensively affiliated to the University through family, education and career, Laing’s favourite spot is “that little triangle just on the south side of Old Court” in Corpus. You can simultaneously see St Bene’t’s Church, the oldest building in the county, and the roof of the Cavendish laboratory, where the internal structure of the atom was discovered. It serves as a reminder that “we’re not actually in the business of looking back, but we’re interested in cutting edge.”

A more timely enquiry then – what would he have asked Nigel Farage had he made it to the so called Farage Formal at Corpus, controversially arranged, and controversially cancelled, a few weeks ago? I have to stress the hypothetical nature of the question before getting an answer. “The important thing in all of this is to emphasise what Varsity actually very responsibly did emphasise, which is that an invitation by a fellow is a personal invitation not one by the college.” “He is an interesting but very alarming politician.”

Unsurprisingly for a diplomat by profession, Stuart Laing is not one to become embroiled in student politics. Despite briefly coming under the spotlight in February 2011 after a controversial arms delegation to the Middle East as part of his Deputy Vice Chancellor role, he seems to have a general instinct for political correctness. He refuses to go in for “a whole lot of name dropping” with regards to anecdotes, and declines to single out a favourite place in the Middle East.

On the step up to Master from Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the University in 2011, Laing’s stance is straightforward. “I didn’t find anything surprising but that’s saying something about me rather than about university life.” He seems to have had much the same phlegmatic approach to the Foreign Office: “You just took each new place as it came.”

He was soon asked to take up Arabic, which he learnt at “a little institute in Lebanon, not in Beirut itself but just outside”. He later went on to Brunei, Oman and Kuwait but I ask him about what it was like initially, living under Sharia law with his family in Saudi Arabia. “You find ways round these different customs, legal systems. You accommodate your life to live within them.”

In terms of changes within the service, he is very positive. “The pyramid’s become much flatter and the ministers want a briefing from the person who actually knows the subject.” Today’s recruits and future ones “have a probably more diverse first experience” than Laing had.

Still, it would be hard to imagine a more impressive start to a diplomatic career – the Master’s time as Deputy Ambassador to the Czech Republic coincided with both the Velvet Revolution, marking the downfall of Communism in the country, and the dissolution of Czechoslovakia itself in 1992.

The British had a significant role to play in the process. “The Czechs and Slovaks used to drink a lot, probably still drink a lot, so they had a terrific New Years’ Eve Party, and woke up from their hangovers and said ‘now what do we do?’” “We know that we want a free market pluralist democracy but we don’t know quite how these things work.”

“We [the British] did all sorts of things that were aimed at easing their transition, to a pluralist democracy and a free market economy.” This “may not get your readership jumping up and down with pleasure, but anyway it is a fact, they were very radical, they wanted the pendulum to swing entirely the other way.”

I enquire whether Cambridge ever feels a little safe compared to his past escapades. “Oh what - do you mean boring?” He splutters. “Never boring.”

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026

Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026