Boring postcards get interesting: Interview with Martin Parr

Making fiction from reality: iconic British photographer Martin Parr talks to Louise Benson

It was in a bathroom of a cafe several years ago that I first came across Martin Parr’s work: hung up were several framed images of typical English food – two limp slices of white bread, a fry-up swimming with baked beans, and a lone cup of milky tea. Photographed arrestingly close up, with their stinging colours glowering off the stained white walls, I was delighted by their cheerful showcasing of the ordinary.

Now, I am curious to zoom in further still, and hear Parr’s take on the ordinary and everyday of our experiences here in Cambridge. Having had several commissions lead him here over the last decade, it is with a certain familiarity that he considers the city. Within this, though, I detect an arch note of humour in his remarks upon finding himself in Cambridge – “that most secretive place” – once more. He discusses the difficulties he has been faced with when photographing the city, describing the closeted professors and suddenly-self conscious students encountered here when he was commissioned by The Guardian to capture ten British cities – it is “a challenge to get any kind of access”. Cambridge was the third of those in the series, and he “pushed hard to penetrate its shell”. We focus on the university, Parr stressing how bizarre it is that in a location so rich with a diversity of life – most notably the town/gown split – “photography is ignored and marginalised” as a discipline to be taught and explored.

Reflecting on his experience of teaching photography, Parr notes the “laziness of the students” he’s encountered: “They’ve either got it or haven’t got it”. I wonder, then, what he feels about contemporary photography emerging today. He is quick to counter his earlier abruptness on the younger generations emerging, talking animatedly on his experience of curating the Brighton Photo Biennal in 2010 – “‘I wanted to give a platform to those who I felt were photographing the world in an interesting way; to young photographers who have not yet been seen, and older ones who have a potential to fill.” When asked for names of ones to watch, he quips, “Well, you’ll have to check who featured in Brighton, won’t you? I’m not going to do all the work for you.”

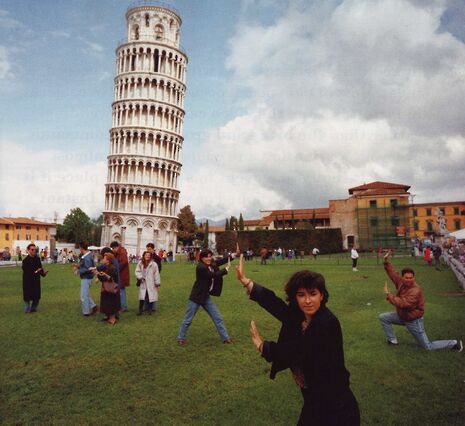

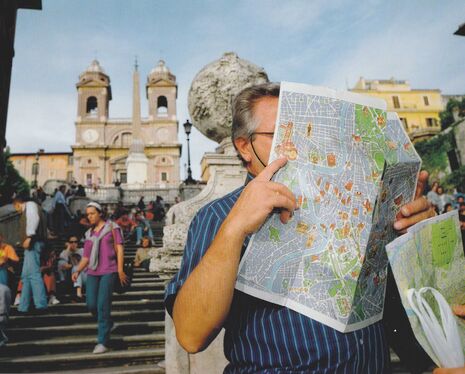

Such flitting between seriousness and straight-faced humour, the gap between the two being navigated almost imperceptibly, characterises the images that Parr catches through his lens. His famed photographs of the seaside town of New Brighton, Merseyside, published in 1986 under the title The Last Resort catch the fantastic banalities – and, on occasion, absurdities – of everyday life. Informed largely by the pioneering colour photographs of John Hinde, the vivid hues of the snapshots imbue them with an excitement, and almost a sickness, that Parr acknowledges when I pitch this towards him, summarising “I regard myself as creating fiction out of reality.”

This brings us to his reaction to being inaugurated in 1994 into Magnum, one of the most influential social-documentary establishments in the world. He describes in plain terms the “partnership and cooperative” nature of Magnum, and “their strength to apply themselves to the commercial world.” It is evident that Parr appreciates the stepping stone that they are able to give photographers, while unashamedly asserting that “It is a broader church than previously, which my being taken on certainly assisted.” I ask whether he would consider himself a documentary photographer at all. Parr pauses over the contradiction that he proceeds to lay out, detailing the ‘‘ambiguity of contradictions even in one frame”, while concluding “But yes, documentary is certainly the simplest and most straightforward reading of my work”. His reticence to resign himself to a terming so simple, though, is clear, and we retread this and find ourselves addressing the humour evident in his work. Parr stresses that it is “Very British – one of the things we do best in this country in irony.

We talk next about his editing process – Parr describes the hundreds of images he takes in order to discover among them just a handful of greats: put bluntly, “If you take more pictures to edit from you’re likely to get some better.” I ask about his grouping together of his work, with over 60 photo books to Parr’s name, where patterns are sought out in ways that never fail to make me laugh. Bored Couples is a favourite, as is Bad Weather: much of his British sense of humour emerges in this placing together of his images.

It is on his vast collection of postcards that we close – Parr went so far as to publish a volume of them under the title Boring Postcards. He describes the postcard as “the most democratic art form”, and the influence of the colour-enhanced cityscapes that populate so many of them sold in unassuming newsagents around the world is clear in his own photographs – although the democracy of the fiction created by his lens could certainly be drawn into question. Parr insists “I am not trying to preach in my images, simply to show one point of view.” As he puts it moments before we end, “It is one way of seeing the world.”

News / Arms divestment would be ‘existential’ threat to the University, says academic5 July 2025

News / Arms divestment would be ‘existential’ threat to the University, says academic5 July 2025 Film & TV / After Hours and the art of a Cambridge night out 5 July 2025

Film & TV / After Hours and the art of a Cambridge night out 5 July 2025 News / News in Brief: Congratulations, Chancellorship, and financial challenges6 July 2025

News / News in Brief: Congratulations, Chancellorship, and financial challenges6 July 2025 News / Academics lead campaign against Lord Browne Chancellor bid2 July 2025

News / Academics lead campaign against Lord Browne Chancellor bid2 July 2025 Science / It’s only rocket science, Elon3 July 2025

Science / It’s only rocket science, Elon3 July 2025