The Air is On Fire

takes a look at a new exhibition of David Lynch’s life and art.

A line of artlovers, cinephiles, and tourists stretches along the Boulevard Raspail. Neon purple tubing reveals their purpose, forming the ominous words “David Lynch” in the aimless haze of the Paris’s left bank. One critic has described Lynch as the “purveyor of all things weird and freaky.” Now, a new exhibition has been unveiled in Paris, taking the first exhaustive look at this director’s “freakiness”.

David Lynch: The Air is On Fire (March 3 – 27 May) is sponsored by the Foundation Cartier (a French exhibition centre devoted to contemporary art) and encompasses painting, photography, drawings, film, animation, installation and sound art from the 1960s to the present. The exhibition coincides with the European release of Lynch’s newest film, INLAND EMPIRE and has been advertised as an accompaniment to the film. It is the ‘director’s cut:’ a real-life analogue of those DVD ‘extra features’. But

David Lynch: The Air is On Fire (March 3 – 27 May) is sponsored by the Foundation Cartier (a French exhibition centre devoted to contemporary art) and encompasses painting, photography, drawings, film, animation, installation and sound art from the 1960s to the present. The exhibition coincides with the European release of Lynch’s newest film, INLAND EMPIRE and has been advertised as an accompaniment to the film. It is the ‘director’s cut:’ a real-life analogue of those DVD ‘extra features’. But

to see the exhibition as a sideshow to INLAND EMPIRE is somewhat unfair. Haunting and lonely, compelling yet repulsive, the images in this exhibition stand alone and apart.

Post-its, matchboxes, and slips of paper depict insects and figures, incoherent phrases and everyday furniture

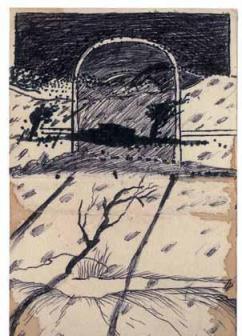

Lynch did not begin as a filmmaker, but as a painter, photographer, and consummate doodler. As a young man, he obsessively drew traces of his inner world onto scraps of the external one: post-its, matchboxes, and slips of paper depict insects and figures, incoherent phrases and everyday furniture. These scraps would go onto become the architectural frame for the worlds of his films – those inhabited and placeless spaces that were always and only his mind. Inspired by artists such as Hopper, Kandinsky, and (above all) Francis Bacon, Lynch attended art school first in Boston and then in Philadelphia where, one day in his studio, a gust of wind took hold of a painting. Image became movement, undulating with the sound in his ears, and Lynch’s cinema, as the story goes, was born.

The exhibition space ingeniously recreates this moment of epiphany, allowing us to enter not only Lynch’s world but his biography as well. The ground floor is divided into two. To the left stand 3D canvases and edited photographs, supported by a mazelike construction of multicolored drapes. Resembling a magician’s cloak or a theatre’s curtains, these gently heaving supports work with the monotonous music projected from speakers above, destabilizing both painting and spectator. On the right is a dark room, claustrophobic with endless scrolls of those previously mentioned scraps. In accordance with Lynch’s request, no dates accompany the drawings. This absence of chronology, a curatorial choice, marks a critical theme. For with Lynch’s paintings, as with his cinema, we will never figure it all out. The past is not a series of linear events and memories aren’t a logical sequence: parts do not compose the whole.

It is this very fragmentation that endows Lynch with such powers of portraiture: of himself, of the women he films. His actresses’ attempts to construct a ‘façade’ of the movie star, a coherent story of their lives, inevitably crack. There is no self-knowledge beyond the endless fracturing of decomposed yet beautiful parts. All that seems left for us to do is descend the exhibition’s stairways, collapse into the plush red velvet seat of a miniature movie theatre (a scene from Lynch’s 1977 film Erasurehead brought to life), sit back, and enjoy the show.

News / Council rejects Wolfson’s planned expansion28 August 2025

News / Council rejects Wolfson’s planned expansion28 August 2025 News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025

News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025 Interviews / GK Barry’s journey from Revs to Reality TV31 August 2025

Interviews / GK Barry’s journey from Revs to Reality TV31 August 2025 Comment / My problem with the year abroad29 August 2025

Comment / My problem with the year abroad29 August 2025 News / New UL collection seeks to ‘expose’ British family’s link to slavery30 August 2025

News / New UL collection seeks to ‘expose’ British family’s link to slavery30 August 2025