POP!

Pop art might not be the controversial movement it once was but there’s plenty to be said about its heritage.

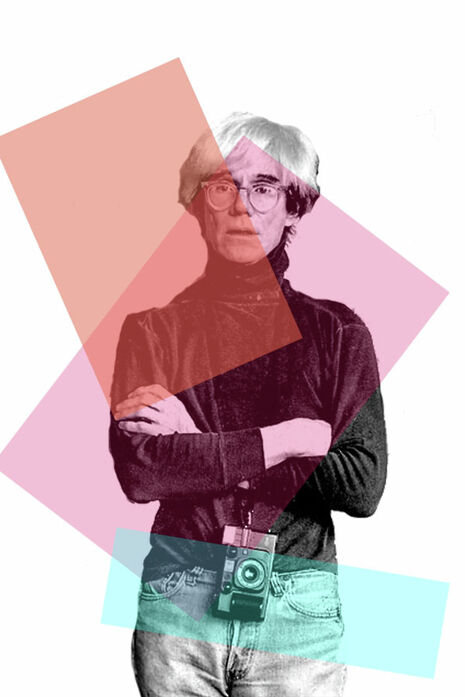

When you hear ‘Pop Art’, you think bright colours, linear shapes and mundane, everyday objects. Yet it is possible to associate the Pop Art movement with a huge range of artists, from Rauschenberg’s ‘Combines’ in the 1950’s – sculptural assemblages of non-traditional objects in innovative combinations – to Michael Craig-Martin’s line drawings in the 70’s. Rauschenberg is often more closely associated with Neo-Dadaism and Craig-Martin explicitly states that his work is not Pop Art, as it focuses on everyday household objects rather than consumerist culture. Nonetheless, I’ve mentioned these two artists to suggest that the term Pop Art might be applied more generally to a type of art which presents itself as a challenge to its more traditional counterparts such as Expressionism and whose purpose is to critique traditional subjects of art by representing what is often thought of as banal. These ideas manifest themselves through Pop Art in a way that provides a sceptical analysis of popular culture and is often accompanied by a sense of urban cultural decay. In terms of artists that engage directly with popular culture, we might think of Basquiat or Banksy – artists whose work is genuinely concerned with being readily available to the public. Using this definition of Pop Art, it can be thought of as a movement that promotes the democratisation of art, wishing to be both intellectually and physically available to the masses. The Pop Art movement has generated a multitude of iconic imagery that can be easily replicated and the notion that anybody can have a Campbell’s soup copy in their house is indicative of its ability to allow everybody to participate in a form of cultural appreciation.

With that being said, is there a certain irony in the fact that Pop Art has become very much a commodity or a valuable investment, when an original Warhol costs upward of £600,000? Surely when Warhol created his screen prints he didn’t envisage that there would be such a discrepancy between the monetary value of an authentic piece and a replica image? In our culture of mass reproduction, it’s exceedingly difficult to put a price on an image, let alone assess whether it is worth paying over 10 times the price for something that is considered ‘original’ but looks visibly very similar to a copy. Sunday B Morning offers a solution to this conundrum, a collective who worked alongside Warhol to create silkscreens that are recognised as authentic reproductions of his Marilyn series, and are direct copies made from the original series (otherwise known as The Factory Series) which Warhol printed by hand. Warhol himself signed the original Sunday B Morning screen prints with the phrase ‘This is not me. Andy Warhol’ which perfectly captures the problematic nature of the relationship between art and printing, and the struggle an artist faces to retain their mark as an individual on a piece that is designed to be mass reproduced – a relationship complicated by the idea that the purpose of the piece is to give a value to a typically invaluable mass produced object.

Julian Opie is an interesting artist to consider in terms of how democratic his work is. His thickly lined figures are distinctive and the simplicity of his style means that his pictures lend themselves to being transformed into sculptures or installations; his public projects around the world include one in the Dentsu building in Tokyo (2002), Regents Place in London (2011) and of course the Classic Blur Album cover (2000). Yet despite the availability of his work, in his solo summer exhibition last year at the Alan Cristea Gallery, pieces like his ‘Walking in the rain, Seoul’ – a screen print series of 50 editions – were selling for around £20,000. Considering the simplicity of his style and its two dimensional, illustrative quality, it begs to question why his work constitutes quality fine art rather than a type of graphics or illustration which can be accessed everywhere from comic books to the Internet. Andrew Marr, author of A Short Book of Drawing, believes that Opie’s skill as an artist can be attributed to his overwhelming skill at drawing. Marr implies that the Opie’s ability to create figurative drawings that manage to show an apt reflection of everyday life in just a few simple lines is why his images are so enigmatic.

The aesthetic accessibility of Pop Art makes it exactly the sort of art that lends itself towards having a decorative function. It could seem as though there is something reductive in viewing art as if it were piece of furniture and Pop Art is particularly susceptible to criticisms of superficiality, especially when it no longer has the same political implications that it used to. Michael Craig Martin’s most recent exhibition, ‘Fundamentals’, typically features brightly coloured prints of household objects like USB sticks and computer screens, and the show poses the question of whether there is really anything dynamic or innovative about this concept any more, or if is the work is merely ‘fun’. But perhaps its decorative value is a necessary part of art’s purpose to engage its audience and maintain a contemporaneous appeal. Enjoyment of art for its aesthetic value and a deeper emotional stimulation doesn’t have to be mutually exclusive; after all, what is wonderful about art is the way it can evoke an emotional response in the viewer in different ways – be it through bold colours or its comic value.

I spoke to Rebecca Eames from Eames Fine art, whose catalogue includes Peter Blake, David Hockney and Patrick Caulfield, about the lasting popularity of Pop Art. She believes that Pop Art’s increasing popularity can be in part attributed to the way it can be seen as safe, and easy to understand, yet she also commented on the way that its retro style is becoming increasingly popular in all areas of design, and so it is part of a larger cultural trend. Rebecca noted the important role that popular artists like Caulfield have in drawing in clients who will later return to see the shows of lesser-known contemporary artists. The notion that Pop Art can be used as bait for reeling people into the art world suggests that it can be seen as a sort of stepping-stone to other, less accessible genres of art. Its accessibility also means that our constant exposure to this type of work encourages a subtle process of critical engagement with the world around us; by repeatedly being forced to view something removed from its usual context, we are encouraged to keep reassessing our relation to it and the wider world.

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025 News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025

News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025 News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025

News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025 Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025

Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025 Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025

Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025