Why make such a colossus out of Rhodes?

Statues matter, but if we don’t leave history set in stone we risk repeating it

Up until the age of six, all I remember of the news on the television screen was Iraq. Fallujah, Ramadi, Mosul; my geographical knowledge of the country became quite extensive. I remember seeing Lindsey Hilsum, the news reporter for Channel 4, clutching a microphone and calmly reporting of the carnage around her as her frail body rattled on the back of an army tank. Most of all, I remember the fall of the statue of Saddam Hussein. The scene was played and replayed by the news channels, printed and annotated by the newspapers. Everyone was celebrating. It meant that at home, having turned off the TV and folded up the broadsheet, we could go to bed that night with the image of triumph rather than bloodshed seared on our brains. In short, it allowed us to forget the real horrors of war and conquest.

Nevertheless there was a clear rationale behind the toppling of the monument of Hussein, as there was with the Stalin Monument, the dictator’s “gift” to Hungary that was rejected in her October Revolution of 1956. Both men were living at the time, making the possibility of them regaining power a very real one. Tugging down and mutilating their stone bodies would go some way towards boosting the morale of the active resistance.

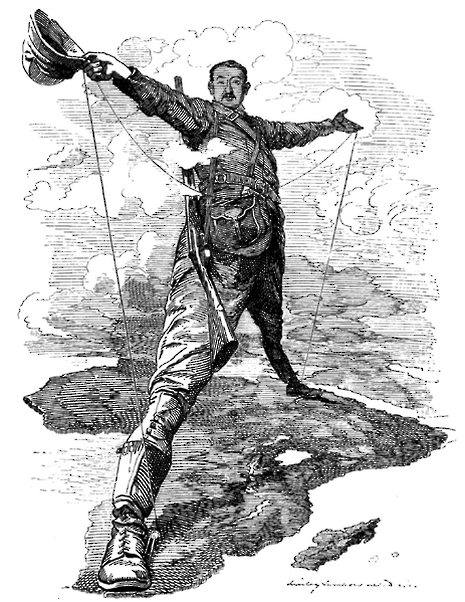

But Mr Rhodes is dead. If in this case we do have a “resistance” (the students at Oriel College, Oxford), what or whom are they trying to resist? Their former alumnus, Mr Rhodes, the colonial diamond mining magnate? That, for obvious reasons, would be impossible. What about a more general sentiment of racism that might linger from imperial rule? That would be something worth fighting against. But the complexity of such a repulsive sentiment cannot be carved into a single statue.

Learning from the past is one thing – and Cecil Rhodes was undeniably a critical player in this nation’s imperial past. But if there is to be any hope of us doing that, then we need to truly understand our attitudes to the past, rather than the past itself. And while it is easy to appreciate the cruelty and bloodshed of Rhodes’s enterprise in present-day Zimbabwe, it is considerably more difficult to see the statue for what it is.

That statue is living proof of our absurd distortion and glorification of imperial activity. If we take it down we aren’t in danger of forgetting Rhodes, so much as forgetting our own propensity to fall into the traps of blithely accepting the invasion and exploitation of overseas territories, and of posthumously glorifying the men who engineered them. The problem with taking down the statue of Rhodes is not that we will forget about the man and the legacy of blood, sweat and tears he left. It is that we will forget that we were once complicit, content to remain blissfully (and consciously) ignorant of the horrors of empire.

That statue is neither Cecil Rhodes, nor is it a mere lump of stone. That statue is a reflection of our outlook on the past. And if we start looking at that statue with equanimity, humility, and (dare I say it) a bit of remorse, then we can perhaps finally make the first step towards progress.

Why do I say perhaps? Because it doesn’t stop there. We need to see the Commonwealth for what it is (the incongruity of a “free and equal” post-colonial community that is permanently headed by the head of the British state), not to mention the New Year’s Honours (how can one be awarded the ‘Medal’ of an empire that no longer exists?). These are equally potent symbols of our failure to come to terms with the loss of empire.

I’m not saying we should scrap these things (whether I would prefer them to be there or not is another matter). But if they do remain, it is important that we radically re-evaluate our attitude to these cultural objects and the meaning with which we accord them. Only then will we able to learn from our past.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Supporters protest potential vet school closure22 February 2026

News / Supporters protest potential vet school closure22 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 Comment / A tongue-in-cheek petition for gowned exams at Cambridge 21 February 2026

Comment / A tongue-in-cheek petition for gowned exams at Cambridge 21 February 2026