It’s time to rethink UK foreign language education

What kinds of foreign language capital does the UK need in the post-Brexit era?

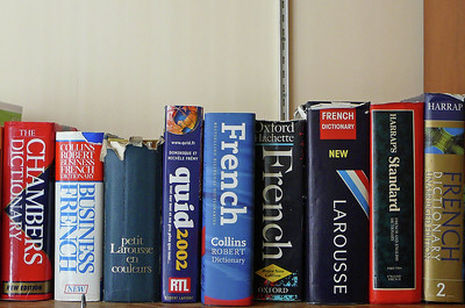

Language education in the UK is worrying: attainment levels are low, motivation to learn a foreign tongue is on the decline, and the languages available to learn in schools — typically limited to French, German, and Spanish — are not at all representative of Britain’s heavily diverse range of global trading partners. Upon leaving school, it isn’t uncommon to hear of people not remembering much beyond the typical ‘bonjour’, ‘wie geht's’? or basic numerals (‘uno’ to ‘diez’). The uptake of some geopolitically powerful languages such as Arabic and Mandarin is even lower due to issues of linguistic distance.

“Fewer and fewer EU nationals will be able to contribute their language capital to the UK”

Brexit has only complicated such trends. Research conducted at University College London and Stockholm University suggests that the impetus behind the decision to leave the European Union is tied to cultural values and national identity — British nationalism and associated attitudes towards immigration trends might have been a driving force behind this choice. I often wonder whether such perceptions stem from the inadequacy of the UK language education curriculum in the first place — either due to the barriers to communication in foreign languages, or the lack of critical thinking on culture and society (particularly Decoloniality) that arises from the UK’s deficient language education.

Pro-leave voters may see Brexit as a reason to toss foreign language books out the window, but the reality is much more complex. The change of immigration laws in wake of Brexit signifies that fewer and fewer EU nationals will be able to contribute their language capital to the UK, whether this be in the form of language teachers and translators, or skilled multilingual communicators. Prior to Brexit, the UK’s lack of language capital caused the nation a whopping 4.8 billion GBP per year, and this number is likely to increase further if national language learning trends do not change.

“I hope for this country to re-embrace the diversity that once made it inspiring”

With regard to language capacity, UK educators have also pointed to difficulty in GCSE and A-level exams, inappropriate teaching methods, and the meagre number of teaching hours as reasons for the declining language uptake in recent years. In my view, technical acquisition of verbs and grammar is one thing, but critical thinking in language education is a more urgent issue worth tackling. At the core of this is what language learning means on a broader spectrum and how it interacts with the British perception of interculturality. In light of Brexit, at this juncture the UK may hugely benefit from a unified goal of learning across subjects — there is some dimension of the foreign language curriculum that may intersect with that of history or geography, and acknowledging and building upon these connections would strongly reinforce healthier and less biased cross-cultural thinking.

The advent of Brexit presents a critical time, now more than ever, to rethink UK language education. The status of English remains key on the global stage, but what does this mean for UK language education more broadly? What sort of language capital does the UK need — economically and politically — and how can this be realistically attained? Looking past the linguistic power of English, how can foreign language education elevate the UK’s understanding of humanity in an ever-growing, mutually reliant global village? Crucially, what are pivotal steps for educators to take in the meantime? These questions, in my eyes as an educational linguist, are far from being addressed to the extent needed.

I love the UK as an international student — it gave me a second chance at life, and I hope for this country to re-embrace the diversity that once made it inspiring. The British Council candidly acknowledged in their 2019 language trends survey report that ’monolingualism is the illiteracy of the 21st century’. The next big step, challenging though it may be, is to transform these words into a solid, culturally accommodating curriculum.

Comment / Not all state schools are made equal 26 May 2025

Comment / Not all state schools are made equal 26 May 2025 News / Uni may allow resits for first time24 May 2025

News / Uni may allow resits for first time24 May 2025 Fashion / Degree-influenced dressing25 May 2025

Fashion / Degree-influenced dressing25 May 2025 News / Clare fellow reveals details of assault in central Cambridge26 May 2025

News / Clare fellow reveals details of assault in central Cambridge26 May 2025 News / Students clash with right-wing activist Charlie Kirk at Union20 May 2025

News / Students clash with right-wing activist Charlie Kirk at Union20 May 2025