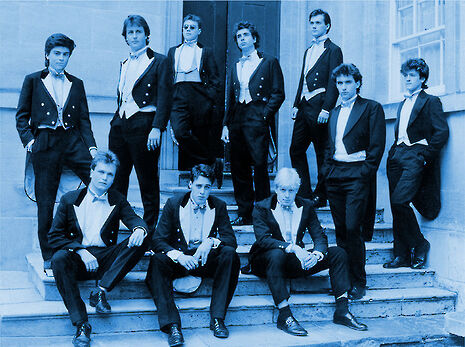

The physical manifestation of our iron-clad class system

For her third column, Anna Cardoso reflects on elitism in Britain, contrasting it to the United States, and suggesting that change should come from those within this conveyor belt of privilege

Ever been to the Houses of Parliament? I found myself there this summer. It really is breathtaking: the vast medieval stone hall, the lush emerald carpeting, the murals that fill the walls. I was taken aback until I realized I felt like I had been there before. It was that niggling sense of de ja vu that made me realize what it was: it looked like my college. I am at one of the ancient ones, but it made me think about how strange it was that our country’s most powerful institutions all look alike. Parliament has bars for aides and MPs that are carbon copies of the college bars we sit in when we have nothing better to do on a Friday night. The spires of our government buildings are much less intimidating to the Cambridge student who sees them every day on their way to lectures.

“This all makes sense in historical context: certain schools funneled the male gentry into their family’s traditional Oxbridge college and then onto the Commons or the Lords”

Our society’s hierarchy can be seen in the walls of the buildings we inhabit. The fact that our institutions of power all look alike gives their residents a sense of comfort in their power: why would you be nervous about coming to Cambridge when it looks just like the school you went to? One need only google ‘Eton College’ to see that it is the spitting image of St John’s. In fact, Winchester College and New College, Oxford were designed by the same architect – William Wynford. This all makes sense in historical context: certain schools funneled the male gentry into their family’s traditional Oxbridge college and then onto the Commons or the Lords. None of this is strange – what is odd, to an American like myself, is how much this is still the case.

Britain’s class system has remained depressingly iron-clad in the centuries since our land was feudal. Access to the best higher education is still a class issue; 62% acceptance of applicants from state school seems like a commendable figure until you realize that only 7% of children attend private school. The lack of diversity – still – in our upper echelons of power, including our own university, is more lamentable than ever.

If you look on the Wikipedia page of Presidents of the United States, you can scan through their alma maters. Of course, you have a few Harvardians here and a few Yalies there, but the universities those men attended (if they attended at all) are diverse – both regional and prestigious. On the other hand, if you look through the universities Prime Ministers attended, there really are only two. Indeed, even more worringly, many of these (mostly) men are drawn from the same few secondary schools. The fact that a few private schools have funneled their boys first into Oxbridge and then into government – and the fact that it is still happening – should be cause for concern.

In America, you do of course, have the occasional privileged boarding school boy who does become President: John F. Kennedy was the son of a senator for example. However, you also had a boy born in a shack with neither electricity, nor indoor plumbing (Lyndon B. Johnson). You had a man who grew up above a grocery store (Ronald Reagan). You have men who could not afford to apply to Harvard or Yale (Richard Nixon). This diversity of experience could not be more starkly different than England’s everlasting classism.

Our institutions of power were literally designed for a certain type of person to glide through them. The buildings we inhabit were made for white, upper-class men to propel them to positions of authority throughout history – and applicants know that. If someone is the first person in their family to attend university, they sit in a very different level of comfort than one who went to a school that looks like the college they now attend. American universities never had the same, ancient class associations. This is not to say that America is a meritocratic dream; evidence has suggested that American grows more and more stagnant in terms of class mobility.

In a time where our country is looking down the barrel of a Brexit-related recession, when the NHS is teetering, and when tragedies like Grenfell are bringing class issues to a head, diversity in power could not be more important.

We need a wider range of opinions at negotiation tables in Westminster. Frankly, that starts with us in Cambridge. I never questioned whether I was the right type of person to apply to Cambridge; I was one of over twenty girls to get in to Oxbridge from my school. I was raised to believe I belonged here. The same is clearly not true for so many students. At Cambridge, your confidence should be based on your intellect – not what school you went to. Us private school bred kids should recognize our positions of power – and use them to try to help broaden access to this ancient institution that will inevitably continue to breed the next generation of this country’s elite.

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025