We don’t care about refugees: five lessons from a 13-year-old Syrian boy

In her first of four columns, Tasha Staines finds some home truths from an unlikely source

Children have always been capable of saying what adults won’t. That raw honesty is something that appears to become lost behind manners as we grow older. Yet in the midst of a crisis, that honesty is often just what is required. When the world of adults becomes chaotic and stressful, it's very easy to forget just how much children observe and take in. When given the chance to express them, their thoughts can teach us all something too.

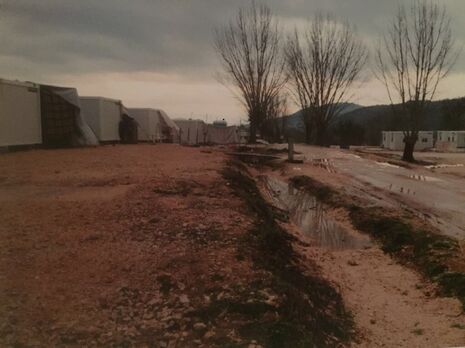

Working alongside refugees in Greece, I was able to make up my mind about a lot of things. I was able to see that Europe’s efforts to curtail this crisis are shambolic; I was able to learn from real people about the perils of the home they had fled;I was able to see first-hand collateral damage personified.

The most valuable thing I learned came from a thirteen-year-old child living in one of the camps. We were talking one day and he explained to me how nobody in Europe really cares about refugees.

"If you walk down the street and ask the average person the difference between a migrant, an asylum seeker and a refugee they will not be able to tell you"

He told me that he thinks we don’t care about refugees because we don’t know any refugees. And this got me thinking. The term refugee should be synonymous with those in desperate need, fleeing persecution. As a signatory to the Geneva Convention on Refugees and Asylum, our legal responsibility is this way inclined. However, the prevailing sentiment on refugees is sadly quite different. Cardinal Basil Hume once said: "It seems to me that the reception given to those applying for asylum is an illuminating indicator of the state of a society’s health." A UNHCR report found that ‘Britain’s right-wing media was uniquely aggressive in its campaigns against refugees and migrants.’

The terminology used by media in the UK means that if you walk down the street and ask the average person the difference between a migrant, an asylum seeker and a refugee they will not be able to tell you. This has had a huge effect on public opinion. People don’t understand who these people are, and therefore don’t know if they should be helped, ignored or worse, feared. Dehumanising terminology such as ‘migrant’ has had a hugely detrimental affect on public opinion.

He also told me we don’t care about refugees because we can’t understand them. Establishing that he wasn’t talking about language barriers, I began to understand the problems of our separate cultures. Every refugee from any country in the world travels to a foreign place and is expected to settle into the ‘foreign’ way of life. And whilst you can argue the right and wrongs of this, the point is that even the worlds greatest do-gooders can sometimes not do right for doing wrong.

Take, for example, the bags of donated clothes I was distributing in the camp. T-shirts with topless women on them, short skirts and low cut tops were amongst the things I received back. Some of the very young girls became upset that there was nothing at all that I could offer them. And whilst the people donating the clothes thought they were helping, in front of these young girls I was left embarrassed for the ignorance and that I had nothing substantial to offer them.

He told me we don’t care about refugees because we hide them. Not only by placing them in empty military camps miles from the nearest town, but by not including them in our national narrative. We don’t often hear of success stories of refugees living in the UK, nor does the news feature the deaths of those killed trying to cross over from Calais. We ignore the crisis in return for a faster-paced news story. We don’t lack the resources to help these people; we lack the political will. And while this "out of sight, out of mind" approach continues, there's no surprise that these people feel like Europe's secret burden.

He told me nobody wants him in ‘their’ country because he’s not a baby any more. This one puzzled me slightly until he told me the story of when he tried to go to school in Greece. The children in the camp I worked in had been permitted by the Greek authorities to attend a class once a day in the local school. Some neighbourhood people felt the refugee children might be dangerous because of the state of their mental health after what they have seen. They protested and blocked their entry into the school, shouting racist and threatening remarks at the children. Eventually the authorities scrapped the move.

He concluded that therefore obviously we don’t care about refugees, and that's why there are so many rules: so many rules about things I can do and he can’t, and rules about where he gets to spend his future, now largely out of his control. He’s taught me that beneath the political chatter and masked racism, you can't fully appreciate someone's suffering until you can look at someone and think 'that could be me'. And we can’t do that with refugees. That's the issue. It's hard for us to relate, and therefore we don't. Consequently, we are unable to adequately care. We are detached.

People aren't bad because they don't care enough. It's understandable. Frustration won't aid the solution in this case, but understanding the problem is the key to fixing it

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025