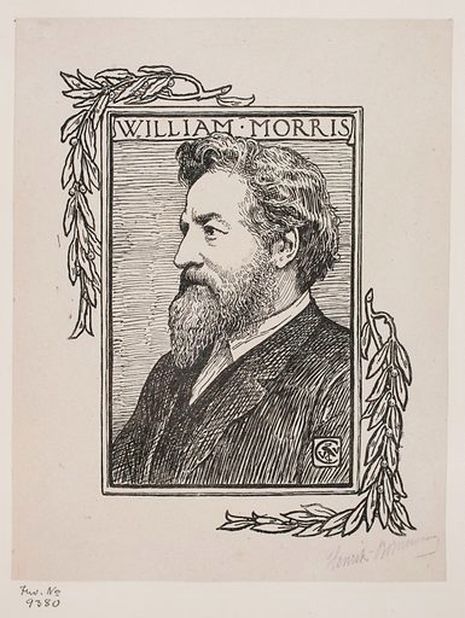

The radical accessibility of William Morris

The openness and egalitarianism of the Arts and Crafts movement opened the door to my love for art, writes Thea Redmill

The first time I entered London’s Victoria and Albert Museum I felt like a child seeing their presents on Christmas morning, stunned by how the ordinary world I live in was so quickly transformed into a collection of ornately decorated artefacts. Exhibit after exhibit of Pre-Raphaelite beauty invited me into the world of the Arts and Crafts movement, culminating with the work of Victorian artist, William Morris. Yet, while visually marvellous, my adoration, my hagiographic stance on him, derives from the ethos of his art and ideological movement behind it.

“Morris freely applied his socialist views to his art despite living in an era of Victorian frigidity”

Born in 1834, Morris was part of a circle of artists known as the Pre-Raphaelites: a Victorian movement who aimed to escape perceived rigidity of contemporary productions and instead took inspiration from the decadence of the Renaissance. Feeling a lack of creativity in the arts scene of his era, Morris sought to incorporate the natural world in his art, without needing to justify his work: he created because he loved to do so.

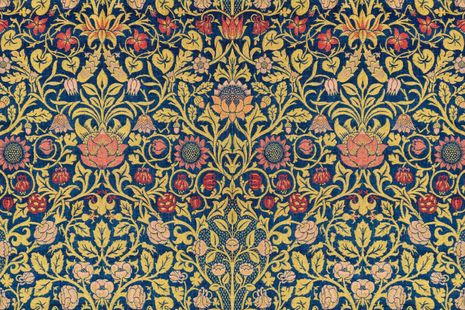

Strawberry Thief, one of his most iconic patterns, perfectly demonstrates this. Birds, strawberries and plants merge together to create a totally original depiction merging romantic, outdoor motifs with pattern and colour. We can see a stark contrast to the industrial nature of Victorian society. This is commonplace with most of his other works and the V&A is just adorned with them.

Indeed, his influence can be seen in a plethora of modern examples. Bohemian celebrities like Florence and the Machine absolutely exude his aesthetic. Her iconic ginger locks spark a connection with Elizabeth Siddal, muse to the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, and her flowing, patterned gowns nod to Morris’ patterns.

Yet, most important to me is the political context which surrounds Morris. He freely applied his socialist views to his art despite living in an era of Victorian rigidity. He aimed to escape the stereotype that art required refined and sophisticated knowledge in order to be understood. Religious context, Latin references and classical symbolism dominated his contemporary artistic field but Morris reacted against this with an egalitarian approach to his craft; aiming to create something that was beautiful for beauty’s sake, not to exclude others through a secret club of educated individuals.

“Maximalism, nature and colour – all these motifs associated with decadence can be enjoyed by all”

I love finding his style in everyday scenarios. His own company, Morris and Co, still produces his prints today, ’crafting’ sofas, blinds, curtains and wallpaper — to name but a few. The idea that the work of a renowned artist can be acquired by the masses applies his vision to modern day, emphasising a beautiful longevity to his worldview.

What is so special is the accessible nature of his work. Often art that defies class aligns itself with a more brutalist tone, aiming to reflect the grit or reality of the group it is meant to be reflecting. However, Morris’ output taught the art world that beauty doesn’t have to be excluded to one, elite group. Maximalism, nature and colour — all these motifs associated with decadence can be accessed and, in fact, enjoyed by all.

For me, seeing his work — be that in a museum (might I emphasise, as Morris would have wanted, one that is free to enter such as the V&A) or in a variety of homes acts as a reminder that creativity is not designed for just one group. The world Morris envisioned does not reserve simplicity for the people and splendour for the rich. Instead, he teaches us that design is for all. Thanks to him, colour, expression and vibrancy are not guarded off for only those elite enough to have an aesthetic. Instead, when I wear patterns or colours nodding to the effervescence of this era, I don’t just feel good, I feel empowered by the voice who extended aesthetic to all.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026