Female rage reaches menopause age: Carrie at 50

Laila Hussey breaks down exactly what keeps drawing us back to the fiery cultural classic, half a century on

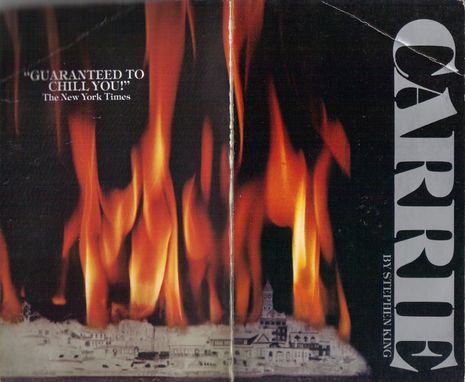

These days, Stephen King could probably get his grocery list published (and it’d be a bestseller). That’s the reward of a long career churning out classic fiction on a yearly basis, providing the world with some of its most iconic villains – Jack Torrance, Pennywise the Clown – and its most Oscar-potential source material – Stand By Me, The Shawshank Redemption. But before there was Cujo, Misery, or The Green Mile, there was blood on a prom dress. Blood in a locker room shower drain. There was Carrie.

Stephen King, the greatest living American storyteller, celebrated a considerable milestone in the last week: his first publication turned fifty years old. It’s impressive enough that with every novel King puts out, he practically has a safe seat in the bestseller list. But while any Colleen Hoover can take people’s money, not every writer can leave something behind with the reader. What makes Carrie so relevant still fifty years later? Perhaps it’s the classic Brian De Palma adaptation from 1976 that people return to every Halloween. Maybe it’s the 2013 remake with Chloe Grace Moretz and Julianne Moore (unlikely). Most likely it’s her, the teenaged titular character, Carrie. Beset on all sides by her abusive and zealous mother, her venomous classmates, and her own uncontrollable power, Carrie is a tinderbox, throbbing under this pressure like an infected gash.

“The skill of the work is the fact that some small, perverse part of us thinks Carrie deserves it”

We know there’s tragedy to come – there has to be, there’s only so much abuse a teenage girl can handle. But the skill of the work is the fact that some small, perverse part of us thinks Carrie deserves it. King taps into the high school mentality that vilifies and ostracises the pathetic and different, the kind of mentality that says I’m glad it’s you and not me. (This is the only misstep of the De Palma film – Sissy Spacek playing Carrie proves the cruel truth that the difference between quirky and unsettling is largely determined by how conventionally attractive someone is). But when I think about the awful climax of the book, I feel fear, sure – that’s the Stephen King special – but I also feel tears welling up.

Who deserves what Carrie goes through at the prom? It’s the Rosemary’s Baby horror, the idea that you’re the punchline of a joke everyone is in on, even the people you thought wouldn’t be. And in this, the denouement of the book, King articulates a timeless anxiety and latent desire of so many readers – especially young women. People are like dead wood: they only weigh you down and give you splinters. Carrie knew this best, and that fire was the best remedy.

“Carrie has shown up in a dozen different tales, with a dozen different names”

King is telling us something about the alienation of the outsider, and the cruelty of those who keep them out. But morality aside, it’s a revenge fantasy. That’s the enduring appeal of Carrie. When King was first conceptualising Carrie, a character he said was inspired by a few tortured and abused girls he knew in his childhood and in his adult life as a teacher, he could never have known how powerful of an archetype he was articulating in her.

While Carrie has undoubtedly remained relevant during her fifty years in culture (even the drunk girl I met in the club bathroom on Halloween knew immediately who my costume was meant to be), Carrie’s real power goes beyond the continuing book sales and film adaptations. Carrie has shown up in a dozen different tales, with a dozen different names. Audiences love Gone Girl and Midsommar, partly for that sick-giddy feeling we get watching the mistreated girl finally do something deliciously destructive. It’s the satisfying power shift that occurs when the chronically overlooked character finally gets everyone’s attention, but for all the wrong reasons. This is a new subsection of media, the ‘Good For Her’ genre, in which the (anti-)heroine gets what she wants and deserves using her greatest asset: female rage. This is a thriving narrative, but before there was that Texan star Pearl and that Promising Young Woman, there was the girl who could move things with her mind. There was Carrie.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026