The Turner Prize 2019 ‘has found its ideal winner’

Ahead of the Turner Prize announcement on 3rd December, Alex Haydn-Williams reviews the exhibition at Turner Contemporary

Every other year, the Turner Prize exhibition, which precedes the announcement of the winner in December, leaves London. In 2019, it’s at the Turner Contemporary in Margate, a gallery with a good claim to be the Prize’s spiritual home. It’s built on the site of the boarding house where JMW himself lodged when he painted the Thanet skies – ‘the loveliest in all Europe’, he called them. On the grey afternoon at the start of October when I visited, I was, to my surprise, inclined to agree. The expansive view from the gallery’s first floor exhibition space over the cold clouds and blue-grey sea is staggeringly beautiful. Though Turner came for the colours, he’d have appreciated a day like this, where monochrome hangs heavy in the air and autumn stretches its bracing fingers.

Murillo’s conceptual ambitions are exciting, but the end product falls short

Which is why it’s a surprise that, in his room, Oscar Murillo has decided to cover almost the entire window. A black canvas blocks out the view of the North Sea, with only a small sliver of sea visible in the centre where the fabric has been slit. Faux-naïve papier-mâché figures sit looking at the canvas with tubes hanging out of their chests. They are supposed to represent the automaton-like humans of late capitalism; the symbolism, though, is simplistic and lacks insight. It’s not clear what exactly it’s all for. Murillo’s conceptual ambitions are exciting, but the end product falls short.

The same is true of Tai Shani’s installation in the next gallery, where fleshy biological forms mix with red velvet in what looks like an unfortunate collision between the Old Vic and Mr Blobby. It’s supposed to host a performance artwork based on Christine de Pizan’s extraordinary fifteenth-century feminist text The Book of the City of Ladies. Unfortunately, Shani’s piece is only actually being performed twice across the entire duration of the exhibition in Margate, so it’s hard to understand it fully: reviewing its artistic achievement would be like looking at a set and trying to assess the actors.

The advantage of the faintly artificial competition format – four artists, four rooms, one prize – is that the artists’ practices throw one another into relief. At the Turner, Shani and Murillo’s approaches are made to look silly by Helen Cammock and Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s seriousness. Both Cammock and Hamdan don’t just allude to political issues: they engage with them.

Video forms the keystone of Cammock’s exhibit. In her film The Long Note she uses archive footage alongside her own to dig into the monolithic, mostly male history of the Troubles and find the histories hidden below its surface: the women in the protests, the mothers mourning teenage sons, even Bernadette Devlin, the only MP present at the Bloody Sunday march. Cammock, a former social worker, is a talented listener: her interview subjects open up at length and in depth. She splices the videos together with an innate ear for rhythm, building to one exquisite and unsettling moment when bomb blasts on the streets of Northern Ireland meld into a contemporary Nina Simone performance. This is a reminder that the Irish civil rights movement did not stand in isolation.

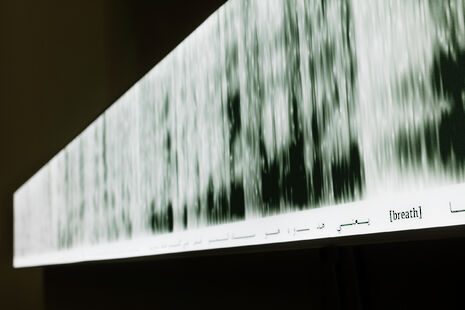

Cammock’s practice is superb, but the most challenging and accomplished part of the Turner exhibition is Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s entry. He’s a self-described ‘private ear’, a forensic investigator specialising in cases involving sound. The works exhibited here derive from the experience of one case in particular. After working with Amnesty International to construct a model of the Syrian torture prison Saydnaya, based only on the sounds remembered by escapees, Hamdan became incredibly aware of the limitations of our sonic imagination.

Most people’s experience of violence is in the cinema, not real life

As he explains in two beautifully-shot, captivating video pieces, projected onto glass in an otherwise dark space, most people’s experience of violence is in the cinema, not real life. As a result, we don’t know what violence actually sounds like: what we think is a punch is actually the work of a foley artist. A watermelon being cut sounds more like a beheading than a beheading does; witnesses in murder trials recall gunshots sounding less like a gunshot, more like a tray dropping. As our memories of new sounds are soon overwritten by a verbal description of them, this sort of comparison, which we use to rationalise the unexpected, becomes the faculty through which the sounds themselves are remembered.

Hamdan, a brilliant storyteller, weaves together examples, from the Oscar Pistorius trial to the murder of Bobby Kennedy, where witnesses describe violence through these comparisons. Throughout, foley sounds clang disconcertingly from speakers hidden around the gallery. It all comes to a shocking conclusion: there’s never been a proper scientific study into the veracity and accuracy of memories of non-verbal sounds. The verdicts in cases based on memories of sounds are, ironically, unsound. Hamdan’s videos are genuinely pioneering work in the fields of forensics and psychology. It’s impossible to see them and ever hear in the same way again. Through artistic techniques, Hamdan exposes the biases of the human imagination, and attempts to overcome them and find the truth. Turner would have loved him.

Since the days of Rachel Whiteread’s concrete-filled semi and Damien Hirst’s cut-open cow, the Turner Prize has been controversial. Recently, it’s become political as well. Up until now, the judging panel’s decision to nominate ‘non-artists’ who work to political ends such as Assemble or Forensic Architecture has only added to the controversy. But this year, in the thoughtful, exquisite and undoubtedly political work of Lawrence Abu Hamdan, the modern, activist Turner Prize has found its ideal winner – and Britain has found one of its most talented and important young artists.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025