Painting reality – an illustration of Mexico City

Fiona Xia shares her experience of creative Mexico City as part of Varsity Arts’ feature on art beyond Cambridge

"In Mexico City there is never tragedy but only outrage”

This opening line of the novel Where the Air is Clear by Carlos Fuentes kept flashing through my mind as I fell severely ill upon arriving in Mexico City. It was the rainy season. Woozily, I would hear the rain bouncing and pinging aggressively off the tin roof; then in the blink of a heavy eye, dead silence. Had it really been raining? I felt like I was standing on the edge of reality, almost certainly due to my light-headedness, yet paradoxically I began to see my personal tragedy morphing into a tale of magical realism. Having recovered, I set off on a journey to explore this artistic city and unearth the traces of the writer’s outrage.

Literature is destined to be problematic and intricate given the country’s colonial past and struggle for independence

Fuentes’ novel depicts the social strata and modern history of Mexico City, and of Mexico by extension. This is destined to be problematic and intricate given the country’s colonial past and struggle for independence. The reflection of this detailed history is best exemplified in XX en el XXI, the first permanent exhibition presented by the Museo Nacional de Arte. The exhibition consists of paintings by avant-garde artists from the Mexican Muralist school. It narrates how Mexico plunged into revolution in the wake of modernity and the consequent reconstruction of the national identity.

La Revolución by Manuel Rodríguez Lozano is amongst the best works exhibited. A masterpiece from his so-called “white period”, he depicts a scene of Piedad using cold colour palettes and skeletal, if not ghost-like, human figures, symbolising the physical and psychological violence that prevailed during the Mexican Revolution. Fuentes portrays a country torn by its allegiance to the Revolution, whereas Rodríguez Lozano conveys his outrage in a more visual and graphic way –a true interpreter of the Mexican people and their pain.

Artists felt the urge to take on a unique Mexican identity by honouring indigenous Mexican culture

Another theme present in Fuentes’ and contemporary intellectuals’ works is the intrinsic contradiction in their relationship with Europe. Despite their European heritage, artists felt the urge to take on a unique Mexican identity by honouring indigenous Mexican culture. This conscious effort is seen in Las Tentaciones de San Antonioby Diego Rivera, an original take on the story of the Temptation of Saint Anthony. In this oil on canvas, anthropomorphic radishes form grotesque figures, replacing humans in this religious scene – a direct response to the Oaxacan tradition of using radishes to recreate nativity scenes. Nevertheless, it was his wife Frida Kahlo who brought the Mexican national and indigenous traditions into the international limelight through her art.

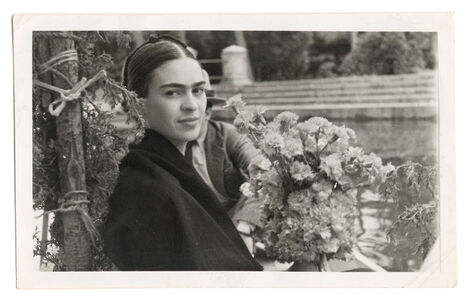

Kahlo is perhaps the best-known Mexican artist in the art world, not to mention in pop culture, thanks to her iconic eyebrow. Mexico also owes her a debt of gratitude, as tourists flood to Mexico City to see her residence-turned-museum, known as la Casa Azul. Nevertheless, the overlooked Museo del Arte Moderno houses one of the most significant works by Kahlo, a double self-portrait named Las dos Fridas. In it, Kahlo visualises her physical pain by depicting bleeding wounds, a device used in the majority of her paintings. Yet the work is a narrative of her separation from Rivera in 1939, and simultaneously an expression of her artistic maturity. Her outrage at constant agony and Rivera’s betrayal was not only transformed into a passion for art, colours sex and life. It also underlines the creative facets from which this oil on canvasemerged: one Frida adored and the other abandoned by Rivera, yet both surviving by the physical sharing of their hearts.

Mexico City is constantly praised as the cultural centre of Latin America, as it showcases the history and social development of the whole continent through art. The current exhibition Cuba, la singularidad del diseño (Cuba, the Singularity of Design) in the Museo del Arte Moderno is a brilliant example, as it examines design and architecture whose conception adheres to the ideological guidelines of the Cuban Revolution in 1959. As opposed to the hostile attitude the Western world holds towards the revolutionary government, Mexico adopts a more empathetic view towards their cause, having gone through similar struggles. This Latin American solidarity emphasised by Che Guevara gives rise to cultural exchange between the two countries, exemplified by Cuban artists Clara Porset and Félix Beltrán who both settled in Mexico City and feature in this exhibition.

When I think of Mexico City, I think of colourful colonial houses, their ivy-covered, Juliet balconies juxtaposed with hot and steamy taquerías; a professional dog trainer joyously trots away with fifteen dogs on leashes to the rhythm of street vendors’ hawking. Fuentes’ outrage is perhaps the richness of this moving, if not relentless urban tapestry, a spirit that has been fuelling artistic creations in the city for generations. This eclecticism and complexity makes Mexico ineffable. As Fuentes puts it, “One does not explain Mexico. One believes in Mexico, with fury, with passion.”

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025