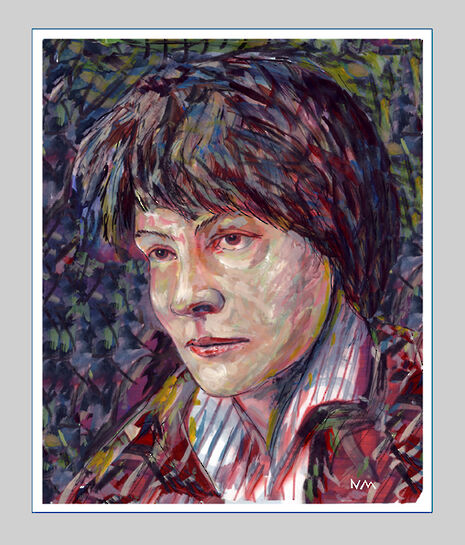

Iris Murdoch – the Philosopher-Novelist at a hundred

With 2019 marking Iris Murdoch’s centennial, Samuel Isaac reflects on why her writing is so important to him

A few months ago, and as for so many others, the pressures of the final weeks of May had become overwhelming. Storming out of the library, frustrated and dizzy, I made my way to the College gardens in the faint hope that Nature could somehow inspire the third paragraph of the timed essay I had just postponed. Staggering into the light, I began to walk slower and as I looked at the stillness of the trees, for a second, I really did forget why I was there.

Iris Murdoch, in her central philosophical work, The Sovereignty of Good, described a similar phenomenon. “I am looking out of my window”, she described, “in an anxious and resentful state of mind, oblivious to my surroundings… Then suddenly I observe a hovering kestrel.” Immediately, “in a moment everything is altered. The brooding self with its hurt vanity has disappeared. There is nothing now but kestrel and when I return to thinking of the other matter it seems less important.”

For Murdoch it was the everyday experiences of life that concerned her

To the detriment of my essay, that was also the case for me. Sitting back in the library, my essay lay there unwritten, but now it was trivial and I found it hard to remember that state of complete anguish that I’d felt when I’d sat with it previously. In speaking of the kestrel, Murdoch went further than promoting “perspective”. It would be wrong to present her as only a visionary of exam term self-care. Rather, she argued radically that my experience of losing myself amidst the beauty of nature is in fact, not only vital but ethical and allows for an “un-selfing” at a time when it is in our nature to become entirely lost within ourselves.

These tortures of revision might seem somewhat trivial examples of the pains of the human condition but for Murdoch it was the everyday experiences of life that concerned her. Indeed, writing on philosophy whilst at both Oxford and Cambridge, her critiques focused on the discipline’s inability to seriously consider those ethical considerations that plague each of us, however quotidian. Her prolific work, both academic and fictional, holds a central place in the 20th century British canon and wrestles with these issues with a beauty and sensitivity that I fear might have been lost in the noise of our modern climate.

At her centennial, her imperative to leave myself is a call for me to look and listen to that which is outside and beyond

The Bell’s protagonist is found within the first few pages caught in a dilemma that is painfully mundane and familiar. Seeing an old lady standing beside her whilst she sits on a train, Dora “stopped listening because an awful thought had struck her. She ought to give up her seat.” Murdoch provides a page of deliberation before eventually Dora decides to stand, mulling over whether her early arrival had granted her priority over other travellers, or whether if she had waited long enough, someone else might take on the “duty” instead.

She saw a loneliness however to this complete subjectivity that we feel; an inability to escape our very unique perspective and experience. Trapped within ourselves, the world becomes disorientating and painfully isolated. It was this I was trying to escape from as I ran to the gardens. Decisions mulled over in the mind draw us into ourselves and down a hole of existential angst. We fail to look at the world around us.

It is these embarrassingly relatable inner conflicts that Murdoch argued were absent from the broad systems of Kant and Hegel and must be at the centre of any ethical discussion. It is a revolt against cold systematising and promotes our own emotional experience of things. Her claim that ethics must be lived and must come from how we experience the world is profoundly empowering and retains a modest appreciation that any ethical system will never be able to comprehensively contain all that we are.

For Murdoch, this is our “original sin”, drawing from the work of Freud, our inherent selfishness and self-containment. In spite of this, however, we do find that there are things that can draw us out of ourselves. At my lowest moments, the beauty of a flower, music or a painting can still take me completely by surprise. To empathise with another is a movement away from myself and those selfish concerns that never cease to plague me. True virtue, Murdoch argued, must come from an un-selfing and an appreciation that there is something outside of ourselves that we all share in.

In spite of all the confusion, we are all aspiring for more and for greater

This is Murdoch’s conception of The Good. Although sounding like scary platonic jargon, I see it as her claim that in spite of all the confusion, we are all aspiring for more and for greater. It argues that we all do truly see things as better and worse. The particulars of what those things are might be different, but it is somewhat stabilising that we really do all share a hope for that which is better. This fact makes us less lonely and enables us to communicate, to imagine and to work outside of ourselves at a time when we can feel so entirely alone and secluded.

I write this in a place I hope Murdoch would be proud: looking at the birds as the wind shakes my windows clear of rain. At her centennial, her imperative to leave myself is a call for me to look and listen to that which is outside and beyond. “The world is not given to us on a plate, it is given to us as a creative task. It is impossible to banish morality from this picture”. “We work”, she explains in Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals, “using or failing to use our honesty… our truthful imagination at the interpretation of what is present to us, as we of necessity shape it and make something of it’’. Never a preacher and always a listener, Iris Murdoch’s ethics should draw us all outside, to truly see beyond ourselves, bump into the world and maybe do something with it.

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026

News / Union cancels event with Sri Lankan politician after Tamil societies express ‘profound outrage’20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026