Translating the female voice

Cecily Fasham explores the gender politics in translating fairy tales and the works of Sappho

The act of translating a text, of making it available to people who can’t read the original language, is a political statement. It says, ‘I think this piece of writing is important, and I want to share it. This text deserves to be known.’ The works we choose to translate show what kind of writing we think is significant. They also show us who we think is worth knowing about and reading. Naturally, those writers whose work is translated – especially into English – are going to become more widely-known.

Translation, then, is a way of canon-building – and as we know, the Canon can be problematic. Translation has historically been a method by which underrepresented voices are further silenced. This might include all ‘minority’ voices outside the mainstream, but particularly applies to female voices and writing by women. Often it’s the men of foreign-language literary movements who get translated: men become the voices of their groups, even if their peers are mostly female.

Sappho never intended to be read in fragments; her poems were once whole. It is perfectly reasonable to want to fill the spaces

One case study is fairy tales. If you’ve read ‘Beauty and The Beast’, ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ or ‘Cinderella’, chances are that the version you read was an indirect translation of Charles Perrault, a seventeenth century French aristocrat. Perrault’s tales have been translated time and again and have formed the basis for what we think of as the essentials of fairy tale. What you might not know is that Perrault’s version of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ ends with a moral warning young girls to be wary of the more genteel kind of ‘wolf’, who, in the words of Angela Carter, is ‘hairy on the inside’ rather than the outside. It’s really a story that ends with a man policing young women’s sexuality, and some small-time victim blaming. Fairy tales are often thought of as implicitly anti-feminist, but this isn’t the fault of the genre. The problem is which works have been translated and spread.

Perrault was a man following in the footsteps of various women who had begun the vogue for fairy tales, part of a French artistic movement of ‘preciousness’ (préciosité). At the time, the movement was gendered feminine, satirised by Molière in his plays The Knowing Women (Les Femmes Savantes) and The Affected Ladies (Les précieuses ridicules), yet from this it’s a man’s work that has been favoured. Perrault gained ubiquity through repeated translation, and is still lauded as the father of the fairy tale. The fairy tale’s mothers lie forgotten. Of them, Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy is occasionally translated, but it seems a travesty to me that such a brilliant figure as Henriette-Julie de Castelnau de Murat, a queer pioneer of the fairy tale genre whose tales brim with subversive messages about forced marriage and the place of women in society, has not had her fairy tales translated into English. Wanting to un-silence de Murat’s voice by translating her into English and gaining her wider readership is what got me interested in translation in the first place.

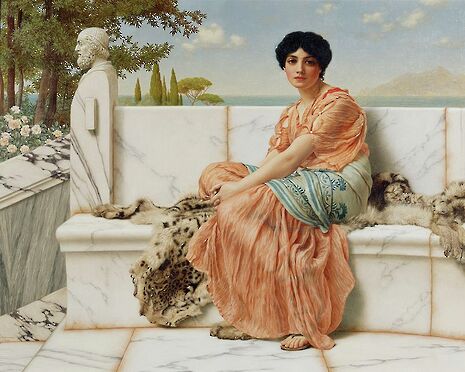

Not being translated, however, is not the only way that women’s voices are silenced. The act of translation itself can also work as a kind silencing, even as it should give voice. The best example here is Sappho. Sappho, though much-translated, is a problem case. She is an early ancient Greek poet, praised by writers and artists from Aristotle to T.S. Eliot. Her poetry survives only in fragments, writing on pottery shards or scraps of papyrus, and her dialect is obscure. What’s clear is that femininity and woman-loving are crucial to her poetry and to what we can gather of her personhood. While translations have historically toned down her queerness, Sappho’s poetry is so rich in homosexual desire that she is the source of the word ‘lesbian’ being used to describe women who love women.

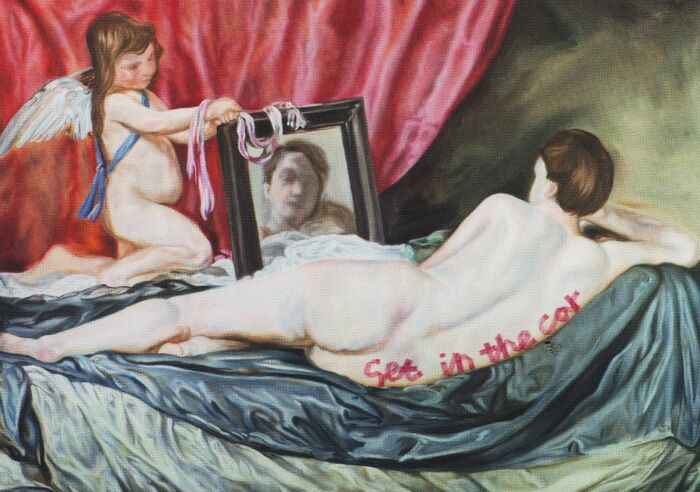

Sappho is a poet of gaps. I fell in love with her through the translations of Anne Carson, which are spare, using only Sappho’s own words and re-creating the fractured manuscripts with inventive mise-en-page. Nevertheless, Sappho never intended to be read in fragments; her poems were once whole. It is perfectly reasonable to want to fill the spaces. It rankles with me to read translator Willis Barnstone writing ‘Sappho appears naked in Greek, so to read her abroad she requires an attractive outfit in English’, an ‘outfit’ memorably described by John d’Agata as ‘sequins, false eyelashes, big heels, a wig’. What bothers me is not the idea of expansive translation so much as the framing of it; a man dressing up a woman, putting his words in her mouth and calling them hers.

Translation is unavoidably tied-up with gender politics – I just hope it can be used to give women writers back their voices, rather than to remove them or replace them with a male idea of what a female voice ‘should’ be.

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025