Discovering Cambridge’s Art: on the body

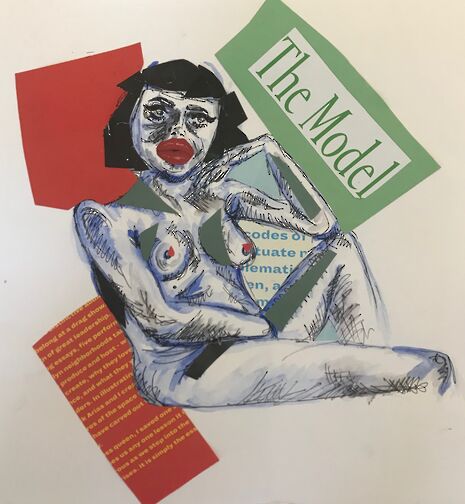

We talk to Ashley Saville, a student creative who draws from her experience as a model in her art to examine notions of the body

Ashley Saville is a student creative, whose work features stunning self-portraiture, capturing herself in bravely introspective artwork. Speaking to Edwin, she reveals that her pieces are a direct response to patriarchal oppressions on a personal scale.

When you work on your artwork, what are you attempting to do or achieve?

In my work I try and respond to my experience as a life model. Drawing from life forces the observer to break up the body into an aggregate of shapes. This process of objective looking negates the paradigms of shame, self-doubt and anxiety that women are trained to relate to their own bodies, and the bodies of others. I like using colour because I feel like it injects some life back into a very stale tradition.

What or who influences your work? Where do you look for inspiration?

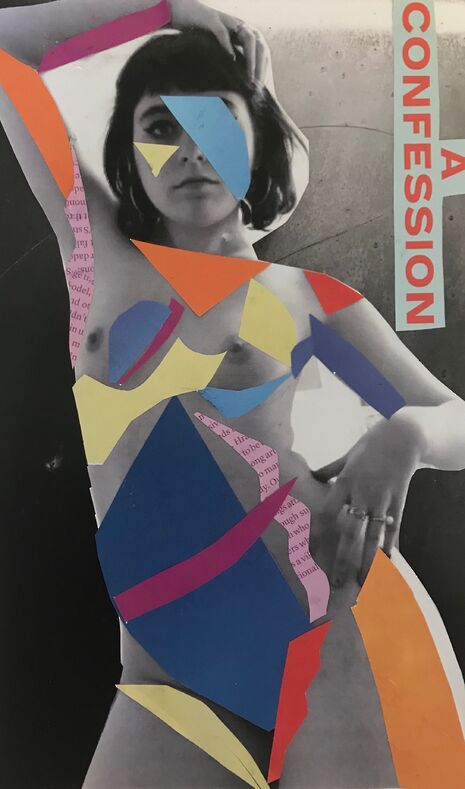

I’m a huge fan of Matisse’s collage; I love how childlike his use of colour and shape is. But I’m also attracted to the political nature of collage as a medium; the anarchic spirit and pointed critique of punk and Dada appeals to me as entirely appropriate means for communicating what I’m trying to say with my work. I tend to source my paper from old zines that I find lying around my bedroom – Posture and Another Magazine are my favourites, they’re always really colourful. When I’m working from photographs of myself rather than drawing someone else, I just use my webcam to take the initial images.

Your work clearly features stunning self-portraiture. If we consider the element of nudity, we can definitely, profoundly appreciate your bravery, but also your immense introspection. Would you say that these two qualities, bravery and introspection, are important in artwork that examines notions of the body?

The body has been a timeless theme in art history since antiquity. John Berger famously deconstructed the male gaze in his text, Ways of Seeing, discussing the treacherous relationship between patriarchal demands and female self-perception. I suppose that in my work, the intimacy comes from responding to forces of patriarchal oppression on a smaller, entirely personal scale. Working from my own body forces me to deal with the aspects of myself that I feel uncomfortable with, or that I dislike; when I work from photographs of myself, I have no choice but to view myself objectively, as if a stranger’s body. I actually think it’s pretty poignant that we consider nudity to be brave, as it is, after all, our most natural state.

Do you think that artwork that deals with female sexuality by a female artist is given the same level of respect and appreciation as artwork that examines female sexuality by a male artist? If not, why do you think this is the case?

I think it’s reasonably clear that our society is not ready to approach the theme of female sexuality in the arts yet, regardless of the maker’s gender. The very fact that Andres Serrano’s Semen and Blood (1990) harbours an edgy cult status while Emin’s My Bed (1998), which incorporates similar bodily fluids, is abhorred and undermined. The worst part is that I don’t even believe this to be an issue of gender bias. I’m thinking specifically of Stanley Kubrick’s film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999), in which the tension between the distinctly male and female compartmentalisation of sexuality is a key theme. Critics called Kubrick’s film erotic and profane – far more so than A Clockwork Orange, in which virile sexual violence predominates – and I believe this to be on behalf of the film’s unrestrained depiction of the female libido.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026

News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026