If Crushbridge be the food of love, play on

This week’s practical shitticism essay explores the romantic lyrics of the online phenomenon known as ‘Crushbridge’

From the surface, it seems as if Crushbridge is effectively an anonymous lonely hearts club based around Cambridge students’ crushes. But no no, do not be misled. Crushbridge is a highly sophisticated, avant-garde poetry publication.

It is a complex, mutable, liminal space within which contradictions co-exist. Even its title – ‘Crushbridge’ – is a portmanteau of the seemingly inextricable sides of fancying someone: firstly, the desire to bridge the gap between the two of you, and secondly, the crushing sense of fear and anger at their unreciprocated power over you.

Let’s explore these ambiguities and mutual contradictions in three example poems published by the popular Facebook page recently.

The following poem was birthed into cyber space on 25th February:

AN ODE TO THOSE WHO WRITE GENERIC UNSPECIFIC POSTS ON CRUSHBRIDGE

‘To that girl who has brown hair’

‘To the girl who once ate a pear’

Why yes that’s me I say!

‘You looked at me, then looked away’

‘I chatted to you the other day’

Yes indeed that has occurred,

You’re talking about me, if not that’s absurd.

I fit the description well enough,

And if others do too, well that’s just tough,

I’ve had my eye on you for a while – let’s meet at a bar.

If only I could know who you are.

To Crushbridge, and to all those who wrote,

Thank you all, for giving us (false) hope.

At first, the reader assumes that this is a poem written in rhyming couplets. However, after “say” and “away” in the third and fourth lines, the poet then includes another line with the ‘ay’ rhyme scheme. ‘Ay’ ‘Ay’ ‘Ay’, I hear you say (as you read the poem aloud), ’what do those “ay” words signify?’

Well, young reader, let me explain. The poet suggests the possibility of romantic pairing by writing in pairs – literally creating their desired ‘couplets’ – but then brutally disrupts this dream by inserting or removing a line from the pair. In this way, the rhyme scheme mimetically enacts the poem’s theme of (false) hope.

The number of lines used to create this poem is also apocalyptically significant. At first glance, it would appear that there are thirteen lines (an unlucky number in and of itself, suggesting the poet’s remorse at not ‘getting lucky’ from Crushbridge). However, I would argue that the poet has hidden a fourteenth line, right beneath our noses (or should I say, right above our noses!) in the title.

Fourteen is the standard number of lines for a sonnet, which is the quintessential medium for love poetry. By including this suggestion of a 14th line, which is at once a denial of a couplet and a title, the poet manages to make the poem a sonnet while also denying the sonnet: in other words, they manage to have their pear and eat it.

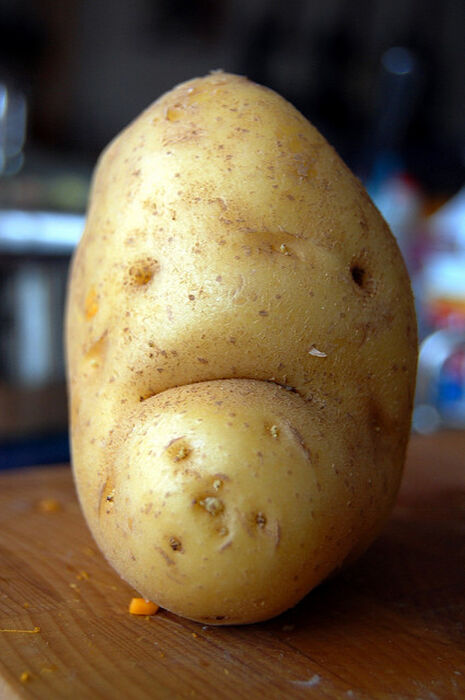

“This radical poem destabilises our expectations as readers. Are we meant to think that the poet truly is a root vegetable?”

The poem contains several beginnings of letters. In these embedded epistolary works, we are only ever told who the poem is to, not who it is from. Indeed, the repetition of “to” occurs eight times in this short poem, if you include its appearance in the words “too” and “tough” (which I do, because I am not an idiot).

This motif is a sophisticated aural wordplay: when said aloud, ‘to’ is a homophone of ‘two’. Once more, the poet has subtly threaded the possibility of romantic union between two people throughout the poem, only to then deny this union. Bravo.

Lastly, I would like to draw your attention to the way that the poet uses parenthesis in the final line, around the word “(false)”. Oh, poignancy! In one way, these brackets partially hide the word. We imagine it whispered, or eclipsed: it is as if the reader is given the choice to read the poem with or without this word; the choice to believe in true hope, or the choice to have cynicism.

Ironically however, because it is the only use of parenthesis in the poem, these brackets actually emphasise the word within them. The use of brackets around the word “(false)” thereby enacts the implied reader’s attitude towards Crushbridge: it repeats that doubleness of hate and longing encapsulated within the very title ‘Crush-bridge’, and expounded within the poem’s simultaneously playful and vindictive message.

On Sunday 5th March, this enigmatic word-poem appeared to Crushbridge’s readers:

WHEN YOU LOOK AT CRUSHBRIDGE AND CAN’T RELATE BECAUSE YOU ARE AN EMOTIONLESS POTATO I would actually like to have a crush on someone life is getting boring.

In 1974, American philosopher Thomas Nagel wrote an essay which asked the famous question,“What is it like to be a bat?”

This Crushbridge poet is clearly in dialogue with the philosophical debate on consciousness when then they pose the similar enquiry: what is it like to be an emotionless potato? This radical poem destabilises our expectations as readers. Are we meant to think that the poet truly is a root vegetable? Are we meant to believe that a spud form which has developed sentience and literacy would be without any sense of feeling? (The vegan community would be greatly shaken to hear that some taters can have emotions. To be honest I think even some carnivores would be a little surprised at that.)

Halfway through the poem, the poet changes from all capitals into entirely lowercase, and there is a lack of punctuation, except in the markation of the abbreviation from “CANNOT” to “CAN’T”. The potato-poet clearly feels that there are some punctuation rules which cannot be transgressed (I mean, which can’t be transgressed). These features are distinctive of 21st-century post-syntax internet discourse, and lead us to believe that the potato wants to identify with the trendy, postmodern users of Crushbridge.

Perhaps the potato is a metaphor. If a potato ‘had a crush’ happen to it, it would presumably become a mashed potato. Correspondingly, a person might become ‘mashed’ (ie. destroyed in a car accident, or seriously drunk/high) if they experienced a crush. Perhaps the use of the potato character is actually a harsh satire on contemporary love – exhilarating yet dangerous, self-releasing and self-destructive. Perhaps. It’s worth noting that this poem suggests that “life is getting boring”, as if life as an emotionless potato has been pretty exhilarating up until now. Perhaps life as a potato is okay after all. There is hope yet.

For another important example, let us take this petite poem published on the 25th February:

You’re so vain, I’ll bet you think this Crushbridge is about you, don’t you

This poem is often misunderstood, simply because it takes a literary expert to grasp the complex messages behind it. Fortunately, I am a literary expert. If you rearrange and then completely change the letters in this poem, it actually reads: ‘I have a crush on Lily Lindon’.

Anonymous serenader, you have excellent taste