The sad death of the local paper

It might not be glamourous, but the local press is important

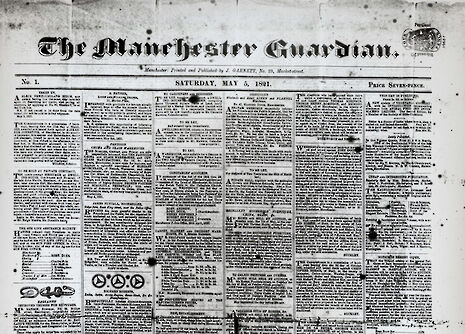

The Audit Bureau of Circulations records that in 1994 over 200,000 copies of the Birmingham Mail were purchased every day. As of 2016, this figure has fallen to just over 21,000. This is a familiar theme for local journalism in Britain today. And while newspaper circulation is down for the national press as well, it is regional news that has taken the biggest hit. Local newspapers can’t compete with the online presence of sites like the Daily Mail’s, which receives in excess of 7 million visits per month, and are therefore falling into obscurity. In a piece for the Guardian, co-incidentally a national paper which was founded as The Manchester Guardian, Andrew Marr neatly summarised the problem: “People who say ‘there are enough newspapers’, are like people who say there are enough public parks or libraries, or piano concertos: always and forever wrong.”

For much of the 20th century, local news was a keystone of social and political life. It may not always have been the most exiting or enthralling of news, such as a recent piece in the nearby Newmarket Journal titled ‘Kitchen hob the most reliable home appliance’ but it had a voice. An important voice which, as of yet, has not been replaced. In the same paper, there was an article exploring how local drug firms had been increasing the price of cancer drugs to the NHS. Beyond recording local events, town meetings, or even the occasional mundane accounts of the winners, runners up and losers of local jam making competitions, local newspapers provided an insight into local communities, a chronicle of social life. As a second year historian, I may be taught to value such records more than many, but with between 100-200 newspapers closing annually, we can all see and appreciate the scale of the loss.

“In the same paper, there was an article exploring how local drug firms had been increasing the price of cancer drugs to the NHS.”

The sociologist Anthony Giddens has argued that modern social life has become disembedded in smaller communities and that the key economic and political decisions have been “lifted out of the local”. However, what does this mean? Should we be concerned that fewer people appear to care about the events of their communities? Or, is it a natural consequence of a globalised world and an increasingly centralised country? I don’t think we should accept such ideas. It must be remembered here, that even the seemingly mundane can reveal enriching details of local events, details which can have national and international consequences. It is striking that the recent events in the country, namely our decision to leave the European Union, split communities and families in a way unseen in British politics in a very long time, certainly in my life time. Equally, though perhaps to a slightly less dramatic extent, the failure of anyone to predict the outcome of the 2015 General Election suggests that we actually know less and less of the politics of local communities and the values of neighbouring families and individuals.

I too am guilty of ignoring local journalism. My previous three articles for Varsity have been on national and international events. This is not an argument that we should forsake national political developments and instead focus on purely regional stories. It is, however, that we should value our communities and their unique melange of people, ideas and histories.

Moreover, we should be worried at the very little we know of the world outside our university and what the consequences of such isolationism are. Cambridge, as many have suggested, is a microcosm. In our colleges we live in accommodation walled off from the houses and flats of non-students. For the most part Cambridge students avoid ‘townie nights’ and consider a ten minute walk to a new pub, venue or shop to be far too much when Sainsbury’s and Cindies are round the corner. When I was at sixth form in Cambridge, my friends and I avoided going into town on a Wednesday because it would be full of students celebrating the end of their week (I am still unsure why we start on a Thursday) and we knew that they were best avoided. These are perhaps trivial examples to draw on and are clearly the results of more than just a decline in local journalism, but nevertheless reveal and inversion in our student lifestyle, an inversion which can be unhealthy.

We are constantly hearing that we are a divided nation. Perhaps some these divisions could be alleviated if we took a greater interest in our communities and engaged in the elections of local councillors and officials. This change starts in local journalism. It is not a panacea and it would not unify our politics or heal the wounds of the chaotic 2016. Ending a decline in local journalism by taking a greater role in the world immediately around us, however, can only prove beneficial for our communities, nation and, indeed, our democracy

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025