The Chapel of Kings

Laura Robinson investigates the events being held to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the completion of King’s College Chapel

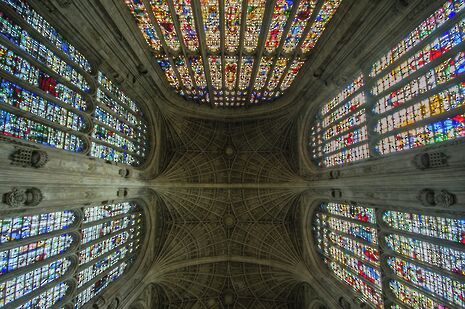

On the 21st and 22nd of October, These Walls is being staged inside the chapel to mark the 500th anniversary of the completion of its stonework, and promises “light, sound, music, voice and movement, contrasting the 500 year old building with contemporary theatre practice.” Some think of the chapel as a heartless monument, an archaic construction that is either met with unconcerned shrugs or starry eyed stares, a part of Cambridge that has been seized by the tourist industry. Yet it breathes the past; a timeline of 500 years alive within its walls and bearing, a living statue that celebrates the colourful history of a town and university, of which we now form the present. It is an education in Gothic English architecture, stained glasswork, and the intelligence and intricacy of its design lies in its fan vault, the largest in the world.

Our tale begins in the early 15th century, when Henry VI was caught with the desire to build a university counterpart to Eton, which he founded in 1440. While the first stone of the college was laid in 1441, the first foundation stone for the chapel was placed by the king five years later, on the 25th of July 1446. Henry drew up organised plans for both Eton and King’s College, though his attention mainly focused on constructing chapels for both institutions, in particular the chapel at King’s, which became the womb of his aspirations. A plan by Reginald Ely, Henry VI’s master mason, was used as the model for the chapel, and while the king laid out instructions for the construction of both the college and the chapel in his will of 1448, only the chapel was ever completed.

The delayed and unfinished building works – including Eton College’s chapel, similar in style yet never completed – were a result of the War of the Roses. While construction continued after Henry VI’s right to the throne was challenged by Richard, Duke of York, in 1455 (patronage by the Duchy of Lancaster, although irregular, continued), it ceased altogether when he was deposed in 1461 by the victory at Towton of Edward of York. Whilst Henry continued to battle for his throne – he was crowned for six months in 1470 – the battle of Tewksbury sealed his fate: he was imprisoned in the Tower of London, and is thought to have been murdered.

During Edward IV’s reign the Chapel was touched very little – the foundation stones had been laid, but the walls were still seedlings – and until his death in 1483, it remained a cemetery of stone, a memorial to Henry IV’s ambitions. The crowning of Richard III sang life back into Henry’s forgotten opus; he pressed on with the building in haste, and ordered the imprisonment of any individual who delayed it. By the end of his reign, the timber roof had been constructed, and the first five bays were in use.

Yet the glory of the chapel was not to be realised until the Tudor dynasty. After his victory over Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, Henry VII cared little for the construction (his attention and treasury diverted to other more consuming matters of importance) and for the first two years of his reign it became a ghost once more. The college solicited the king for mercy upon its chapel, lamenting that “the structure magnificently begun by royal munificence now stands shamefully abandoned to the sight”. Henry VII’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, was dedicated to continuing the legacy of Henry VI, now paraded as a Yorkist saint, and her influence extended to her son. In 1508, the chapel was a beehive of activity, and although Henry VII died a year later, he set aside a part of his wealth in his will to ensure that his son would be able to continue with the edifice.

By 1515, during the reign of Henry VIII, the main structure of the chapel was complete, and finishing details were added until his death. These included the rood screen separating the choir from the antechapel, erected in celebration of his marriage to Anne Boleyn. The chapel stood in its finished glory, a living relic of just over 100 years of history. It would escape harm while serving as a training ground for Oliver Cromwell’s troops during the Civil War (graffiti from Parliament soldiers on the walls near the altar still being visible today), and survive the blitz of World War II, during which most of the stained glass was removed for safety.

Beloved and abandoned during its birth, the chapel is experiencing a similar kind of emotional duality today: tourists stop and stare in awe, while students cycle past without so much of a glance: a literal ‘been there, done that, got the postcard’. It is easy to forget the chapel’s historical magnificence and just see a grainy image cheaply printed on a white t-shirt. Yet to celebrate the chapel, the anniversary of its birth, is to celebrate a part of Cambridge, and thus a part of what we now belong to.

News / Deborah Prentice overtaken as highest-paid Russell Group VC2 February 2026

News / Deborah Prentice overtaken as highest-paid Russell Group VC2 February 2026 News / Christ’s announces toned-down ‘soirée’ in place of May Ball3 February 2026

News / Christ’s announces toned-down ‘soirée’ in place of May Ball3 February 2026 Fashion / A guide to Cambridge’s second-hand scene2 February 2026

Fashion / A guide to Cambridge’s second-hand scene2 February 2026 News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026

News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026 Comment / Men at Cambridge are experiencing equality2 February 2026

Comment / Men at Cambridge are experiencing equality2 February 2026