The Invention of Love

Sarah-Jane Tollan is impressed by this unusual play, performed in the intimate Trinity Old Common Room

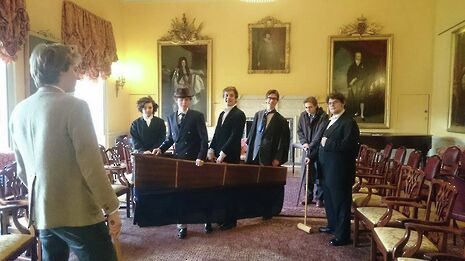

Entering Trinity College’s Old Combination Room is a feast for the eyes; an intimate yet ostentatious space, the walls suffocated with 19th century paintings, the high ceiling glowing by the light of the chandelier. A perfect setting, then, for Tom Stoppard’s The Invention of Love, a quick-witted, energetic portrayal of the life of A.E. Housman, the eminent classicist who breathed in the walls of Trinity as a Professor in the later period of his life.

Touted as one of Stoppard’s more elusive plays, the allusions to the classical world – recitations in Latin and jokes about Catullus – do press down heavy and fast, and it is initially quite daunting to be presented with an opening scene on the River Styx (an inventive piece of staging given the space) with a character ranting about ancient metre. It is the enthusiastic theatricality of the cast, however, that make it accessible; the humour flowed furiously, and before the close of Act One, the majority of the audience were guffawing or grinning. Yaseen Kader gives a rousing comedic performance as Housman’s intellectually snobbish peer, as do David Tremain, Daniel Unruh and Adam Butler-Rushton, effectual roles that aid in easing the tension and difficulty of the subject matter.

The potency of director David Tremain’s interpretation, however, lies not in the fiery, brazen comedy of the piece, nor in its intellectual prowess and flamboyancy, but in the humanity of its characters. Seth Kruger as the young Housman was revelatory; the nervous reservation of an academic mind bursting forth was played to such intricacy in the surreptitious smirks, the anxious touch of a few wisps of hair, the stammering diminuendo of a sentence. It was the interplay between Housman and his elder self, played with all the disillusioned dry wit of Sam Groom, that the play really came alive. A discussion of the classics on a sofa in Hades, at first a mock supervision, becomes a moving emblem about life and love from the elder to the younger.

Yet the strength of the humanity, of the duality of comedy and tragedy, in Act One was unfortunately lost in the second act, which seemed plodding and lethargic. The introduction of the Oscar Wilde case and the baiting nature of the journalistic world were detached and seemed hasty, for all their relevancy to Housman’s life; the emotional potency of the piece dissipated for one of a more socio-historic emphasis, causing it to lose the foundation of pathos that made the primary act so exhilarating.

For it is the focus on human nature, on trying to make sense of a world through the ancient world, that ignites the spark in Tremain’s production. Wildly accessible through its animated cast, it is a beginner’s guide to classics, an intellectual comedy, and a human tragedy, all at once.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025