Pulling the Trigger

Social media, television and journalism all contain trigger warnings. Why not theatre?

Trigger warnings were not something I was overtly aware of until I became familiar with the Cuntry Living group on Facebook (Oxford’s feminist magazine), where I saw scores of posts alerting readers to discussions about rape, suicide, abuse, and other upsetting topics. This seemed to me an inherently sensible idea. As well as a sign of respect for those who have been through traumatic experiences, trigger warnings give people the opportunity to avoid certain material that may prompt a trauma to resurface. These warnings can be found across social media, in articles, and before some television programmes. But why do we not see them as frequently in theatre?

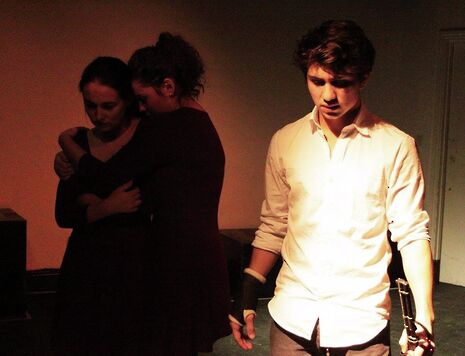

In Lent term last year I directed 5 Kinds of Silence at the Corpus Playroom, a production which centred around physical, psychological, and sexual abuse within a family. It was a very stylised piece, substituting physical theatre in place of more visceral depictions of the violence. As a result we came away with a piece which I am proud to have been a part of, and which handled difficult material carefully, but I still regret not following my gut instinct and placing a warning on the door for the audience. It wasn’t something I had seen done before, and I rationalised that the promotional material, as well as the leaflets handed out on the door, were very clear about the show’s content. A few weeks later, a spectacular production of Philip Ridley’s Mercury Fur was staged at the same venue. For this, there were clear signs upon entrance about the nature of the show, and the same was done the following term at Clare Actors’ production of Her Naked Skin. Yet these are the only two shows I have come across in my year and a term in Cambridge which have decided to place warnings. This definitely does not represent the number of shows I have seen in Cambridge that contain content which could be classified as ‘triggering’.

Of course what constitutes ‘triggering’ is a tricky area, and it is incredibly difficult to even begin to set parameters for this. I have seen warnings on social media for: domestic violence, suicide, eating disorders, rape, assault, depression, and more — but I honestly believe that it would be impossible to create an exhaustive list. Everyone has had such varied experiences, an individual could be triggered by something that seems apparently trivial to those around them. I have seen a number of writers arguing for and against trigger warnings, with some articles claiming that they can actually cause more harm than good. The debate is far too complex to address fully here, but simply from a dramatic perspective I believe that more productions need to be using them.

When it comes to theatre there is a level of inescapability, which is often overlooked. A book can be put down, a television programme turned off, a website closed – but when it comes to plays, things are far more difficult. Of course a person can physically leave the auditorium, but this is not necessarily an ideal situation for a number of reasons. Firstly there is the issue of pure logistics, particularly places like the Corpus Playroom, where for half the audience to leave they must cross the stage. If you happen to be sitting adjacent to the venue’s door then fine, but for people placed in the centre of rows or in inconvenient locations, it can be impossible to leave without causing a great deal of disturbance. Which leads on to the second idea: that drama is a shared experience. I tend to see productions with friends, so if I leave a performance there will undoubtedly be questions — some of which I may not really want to address. But finally, and most importantly, the immediacy and intimacy of live theatre cannot be forgotten; seeing something which you find triggering played out in front of you can be utterly traumatic, it is a very different experience to watching something on a screen.

Drama does, however, have an added level of difficulty when it comes to placing warnings, as often the excitement and joy of the experience is in the unexpected surprises and twists in the plot. We could certainly place a warning up about suicide for a production of Romeo and Juliet, and I highly doubt the audience will feel a major plot point has been spoiled, but for less well-known plays, or pieces of new writing, the use of content and trigger warnings could pose a problem. While this complicates matters, it is not worth forcing an audience member to endure something they find traumatic and triggering, for the sake of keeping a plot twist quiet.

This is not an attack on the Cambridge theatre scene, nor theatre in general, but more about opening up a debate. This summer, I directed a production of The Penelopiad at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival that contained an unpleasant rape scene. The scene was handled sensitively, and my actors were incredible, but when I asked the venue if we could place a warning by the entrance, they informed me it “wasn’t their policy” to do so. Theatres have a legal responsibility to warn audiences about nudity, open flames, strobe lighting, haze effects, mock firearms, gunshots — but not depictions of abuse, suicide, self-harm or any other potentially triggering material. I’m not necessarily saying there should be a legal obligation to do so for this, largely because it would be impossible to compose an exhaustive list, but directors and producers need to consider carefully the idea of placing warnings before shows. I doubt any venue in Cambridge would disapprove of the use of trigger warnings outside a production. Even if just one person is prevented from being forced to relive a traumatic experience, that, surely, is worth it.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 News / News in Brief: carols, card games, and canine calamities28 December 2025

News / News in Brief: carols, card games, and canine calamities28 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025