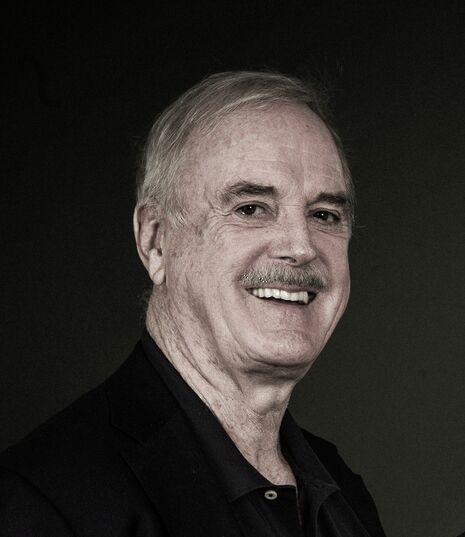

Interview: John Cleese

Alex Cartlidge meets the king of Cambridge comedy

In 1972, a 20 year old student by the name of Douglas Adams was standing at the Round House bar during an interval, when he noticed that the man standing next to him happened to be his comedy idol. Without hesitating, Adams introduced himself and asked the man if he could interview him for Varsity. Despite having graduated some nine years before, the man accepted the offer, gave Adams his number, and on November 25 1972 Varsity published Douglas Adams’s interview with a Mr. John Cleese.

Now, I’m not going to draw any levels of comparison between myself and Douglas Adams, but when I saw that John Cleese was making a one night appearance at the Cambridge Arts Theatre in October to promote his new autobiography So Anyway..., just like Adams, I could simply not refuse to pass up the possibility, however minute it was, to ask John Cleese for an interview. Astoundingly, he accepted, and so I sat down in front of my phone this afternoon, equally nervous and excited, like it was Christmas, about to live a dream that had begun when I first encountered Monty Python at the age of nine.

I start the interview by noting he lists students requesting interviews for their magazines as one of the pains celebrities have to endure, to which he clarifies that this is an exception. “I have an affection for Varsity. I can’t remember if I’ve ever been interviewed by them before, but of course I remember Varsity, and it’s nice to connect with people who’ve had a similar experience to myself.” I take my opportunity to inform him that he has been interviewed by Varsity once before, in 1972, by Douglas Adams, to which he laughs. In a way, I’ve just managed to make John Cleese laugh. I imagine telling this to my nine-year old self, who is cynically dismissive of this ever happening.

Despite having graduated from Downing some 51 years ago, Cleese still speaks of Cambridge with great affection. He has great memories of the Footlights’ clubroom, putting his career in comedy down to the luck of living so close — “I spent a lot of time there because I was incredibly lucky to get digs just around the corner, literally around 100 yards away, and that’s why I think I spent so much time there. If I hadn’t had digs around the corner, I probably wouldn’t be in show business, it’s very strange.”

The clubroom which Cleese speaks of was demolished in 1972, which saddens Cleese, simply because of its importance to developing his comedy career. “We met there all the time, we didn’t talk about show business that much, but every now and again there’d be a smoker. There was this tiny little stage, some little rudimentary curtains and a few lights. Nothing had to be organised. And what usually happened is that on any given evening there were probably four, possibly five, really good bits of material. Well if you did that twice each term, by the time you got to summer term you’ve probably got fifteen to twenty decent bits of material, and if you write a bit more you’ve got enough for a show.” Simple as that.

It was in 1955, five years before Cleese joined Cambridge, that Brian Marber became the Footlights President, and Cleese credits the development of the society to him. “It used to be very Cambridge based, it was all jokes about Petty Cury and Kings Parade and bedders. And then when Marber became president, he said this has got to stop being about Cambridge, it’s got to become more to do with other things, and we want to be able to do stuff that could be done in the West End”. Five years later, in Cleese’s first year at Cambridge, Peter Cook — “a genius, and I mean that” — became President, a man who, unthinkably, Cleese explains, “had two revues running in the West End with Kenneth Williams in them whilst he was still an undergraduate, which was phenomenal.” In his book, Cleese speaks of watching Beyond The Fringe at the Arts Theatre in April 1961, a show so magnificent that he “experienced a reaction [he has] never had since… a pang of disappointment, immediately replaced by exhilaration as the lights came back up”. Regardless of this increasing quality, Cleese is damning of his first Footlights Revue, 1962’s Double Take (directed by Trevor Nunn) – it “just wasn’t terribly good”. It ran for two weeks in Cambridge, before a week in Oxford, “and that was the end of it, nobody ever heard of it anymore”. So the following year, when the 1963 Revue A Clump of Plinths began to run in Cambridge, starring Bill Oddie, Tim Brooke Taylor, David Hatch, “and all that lot”, no-one had an “idea that it was going to do anything other than two weeks in Cambridge and a week in Oxford”. Little did Cleese et al know, but the show, retitled Cambridge Circus, would have such a successful Edinburgh run that it subsequently ran on the West End and Broadway, toured New Zealand and featured on the Ed Sullivan Show. There was even an album recorded by George Martin – maybe it was the Cambridge Circus, and not Monty Python, who were the Beatles of comedy.

Cleese’s autobiography ends in 1969 with the commission of a new BBC sketch show called Monty Python’s Flying Circus. In July 2014 the surviving members of the troupe reunited to perform to hundreds of thousands of fans at the O2 Arena, and Cleese credits the timelessness of the humour to the short rise and fall of satire in the 1960s. “In ’62, British humour suddenly, for the very first time since about the 18th century, became very satirical and biting about authority figures and the establishment. And by the time I got back to England in 1966 people were tired of it, everyone had got fed up with satire, it was overdone – four years of endless, endless satire.” So thus by the time Monty Python started, there was a conscious – “and to some extent unconscious” – desire to react and create something with no topical jokes, and that’s why, Cleese thinks, the material doesn’t age. “The only things we made fun of were things like the class system, which doesn’t seem to have changed as much as everyone thought it would.”

I’m wondering why Cleese has chosen now to write his book. Michael Palin has, after all, been publishing his diaries since 2006. He credits his autobiography to a conversation he had with Michael Caine in Barbados “about ten or twelve years ago”, in which the actor told Cleese that by writing an autobiography “You’ll recover parts of your life which you’d completely forgotten about”. Cleese plans to write at least two more books, presumably covering the Python and Fawlty Towers years – but is not prepared to commit to any content or style just yet. “When you read biographies they say that so and so had dinner in New York with so and so in 1947, and the only answer is, so what? I read an autobiography of a particular film star I’m very fond of, but I read his autobiography for a bit and it was just a list of places he’d been where there were famous people, and I thought, so what?” When I ask whether he found it therapeutic to write about his earlier years rather than Python and Fawlty Towers, he responds in the negative, but clarifies that by going back to the start, he was able to piece everything together – “it was as though in my mind I’d integrated all these different parts of my life, and it felt more integrated than it did before, and it gave me a stronger sense that my life had led up.” By starting from his very first public performance as a schoolboy, he manages to trace how his sense of humour developed into the surreal style that brought him fame, from his beginnings at Clifton College, his Footlights years, up to the pre-Python years working for BBC radio, and on the shows The Frost Report, I’m Sorry, I’ll Read That Again and At Last the 1948 Show (the best sketches of which he proceeds to reprint in the book).

The book has taken two years to write by hand, although he tells me “The thing that takes the time is trying to think of something that you think is worth saying, and then the way that you like to put it down is totally secondary.” He then proceeds to give me an explanation of the painstaking handwriting process – “the nice thing about this piece of technology, this little propelling pencil, is that on the other end from the lead, there’s a little piece of rubber, and if you rub it against what is written on the piece of paper, you can rub it out, and this seems to me an ideal combination”. So whilst he plans to write more, we may have to wait a while before any such books see the light of day: “It’s important to take a break first, otherwise it’s very easy to get stale if you keep doing the same thing, which is the problem for even some of the very best writers...so that’s what I’m going to do.”

There is also the small question of the Terry Jones film Absolutely Anything, which reunites the voice talents of the surviving Pythons, and is set to be released next year. It seems the anger and distance that used to haunt the Pythons has now vanished: “It was a very good experience because when we get together we have a good time and we laugh a lot. But what people don’t quite get is that we’re also very, very different people, you only have to look up each one of us and see what we’ve been doing in the last five years, and you realise we hardly overlap at all now. Now we’re all going off... and we’re all very happy, and if you read the last two paragraphs of the book that will sum it up perfectly.”

Our time is almost up, he must now speak to “Shortlists, or someone, whoever they are”. As I begin to realise that I can’t spend all day talking to John Cleese, and we begin to wrap up, he informs me that I must tell people who come to see his shows not to ask “polite questions”, but instead to “just ask friendly, very rude questions – they’re much more interesting.”

Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026

Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026 Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026 Theatre / The ETG’s Comedy of Errors is flawless21 January 2026

Theatre / The ETG’s Comedy of Errors is flawless21 January 2026 News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 News / Write for Varsity this Lent16 January 2026

News / Write for Varsity this Lent16 January 2026