Review: Edward II

Sian Bradshaw is thoroughly impressed by the quality of performance in this Marlowe Society production, but finds that concept occasionally exceeds realisation.

Modern re-interpretations of Renaissance classics are often cause for concern. As has been the case in the past, conceptual innovations have the potential to either overwhelm source material, smothering and stifling the lyrical beauty of verse as a result of their pioneering, or conversely, to elicit and underline qualities of the text not hitherto explored. Being of this opinion, I was relieved to see that The Marlowe Society’s production of Edward II fell largely into the latter category. Although, at times, the production is indulgent in its self-reflexivity, the strength of its leads and the vivid visual audacity with which it occupied the Cambridge Arts Theatre are aspects of the production deserving of praise.

"This production is particularly perceptive in its interpretation of stage direction and theatrical space"

This production is particularly perceptive in its interpretation of stage direction and theatrical space — matters only dealt with implicitly by Marlowe. A giant and lurid yellow throne sits atop the otherwise scant stage and is the focal point of the play’s action, astutely used as an emblem of grotesque ambition. Boasting a trap door, the prop abounds in its utility, staging the infamous (and problematic) death scene of Edward II, turning as the red-hot poker is revealed. It also serves as a means to separate the stage in which private conversations occur either side, furthering this mood of conspiring against the King. Equally intelligent was the decision to double the characters of Lightborn and Gaveston, providing a psychological complexity to the titular character, so desperate in his dying moments that he concocts but a figment of his former lover, with whom his relationship is now cast in a darker territory.

Yet, as the throne revolves and mutates to the dissonant sounds of ominous circus music amid the return of Gaveston earlier on in the play, the prop bears the words “Welcome Home Gaveston” as though they are the harbingers of death, launching into an absurd meta-theatrical parody through the mode of a Punch and Judy-esque puppet show. Initially, this tongue-in-cheek, proleptic mirroring of the action is amusing, but the joke is drawn out far too long and degenerates into crass caricature that deviates far from the source material, with the puppet-king at one point exclaiming that he is “not in the vagina business.” There is further attention drawn to the artificiality of the piece and there is an almost Brechtian feel to the production, with Edward’s chalked face and characters breaking the fourth wall on a number of occasions, all to no particular effect.

Costumes, too, were hit and miss. The new punk additions to the play do not always make perfect sense. While Edward’s attire (a robe, shabby jogging bottoms and a Ramones t-shirt) formed an appropriate contrast to the pomp and ceremony of his crown, the decision to clothe his son, Edward III, in a Raccoon onesie, tail and all, was rather more confusing. However, the new aesthetic Edward II is re-imagined into is generally quite pertinent, emphatically underscoring the transgressive nature of the play and its eponymous King.

"Joe Sefton excels as an energetic and foppish King who heaps titles on his favourite, Gaveston, showering him with titles above his birth with a childish and reckless abandon"

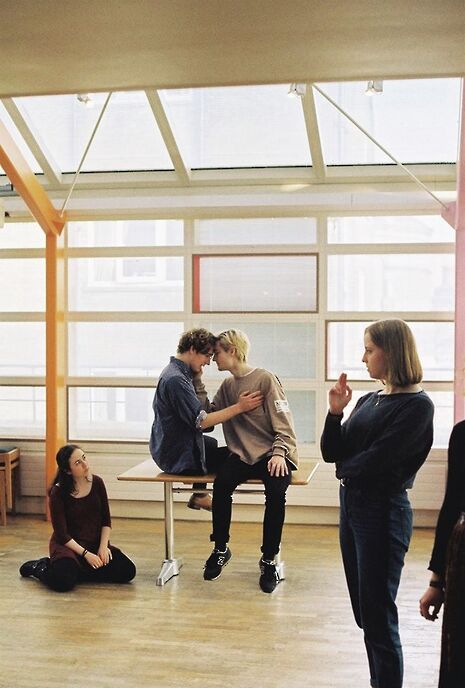

Granted, the few incoherent post-modern additions are not to the detriment of some particularly strong performances. Joe Sefton excels as an energetic and foppish King who heaps titles on his favourite, Gaveston, showering him with titles above his birth with a childish and reckless abandon and later, dwindling into a state of pity. In his despair, his soliloquising is almost redolent of Hamlet, portraying the conflict between the personal and the political. But Katurah Morrish is the stand-out. Delivering a particularly nuanced and stage-ready performance as the jilted (and in this production, pill-popping) Queen Isabella, Morrish adds an allusively feminine and scheming disposition to the role and embraces fleeting moments of comic relief with open arms.

All in all, this production is a fitting showcase of the great theatrical talent the Marlowe Society has to offer. Although, at times, concept does exceed realisation, the production, in the words of Marlowe himself, is not too “swoll’n with venom of ambitious pride” to succeed, and shows the Cambridge theatre scene at its best

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024

Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024 Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024

Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024