Preview: A Doll’s House

Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House is not your typical Victorian three-act, but a play that analyses the advance of individualism, writes Nolan Lindquist

“Do you like Active Child?” Todd Gillespie asks me, optimising a pre-rehearsal playlist. I hadn’t heard of them, but that is besides the point. I was there, in an obscure Pembroke common room, to see Todd and his opposite number, Hollie Witton, get very cross with each other – and get cross they did. After all, Todd is Torvald Helmer, and Hollie his wife, Nora, in the Downing Dramatic Society’s upcoming production of Henrik Ibsen’s proto-feminist Victorian three-act, A Doll’s House.

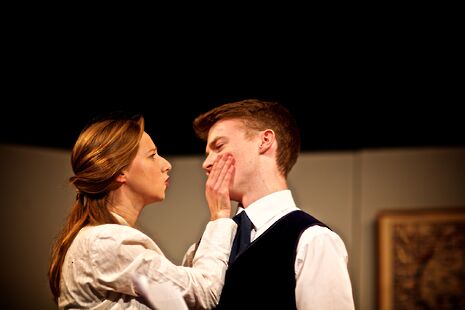

When I stopped by to watch Gillespie and Witton work on that play’s final scene – under the watchful supervision of director Katie Woods and and assistant director Alistair Henfrey – I sat down off to the side of what would have been the stage, slumped in an overstuffed black couch, while the actors circled each other like cage fighters. The tricky thing with A Doll’s House is the tension between its rippling melodrama and the low-key domesticity of it all – when Torvald finds one of Nora’s hairpins, which she’s used to pick the lock of their mailbox, it feels like a murder weapon.

Ibsen’s work, with the Christmas holiday as a key motif, is nicely seasonal. “I think we’re moving it – I’m moving it to England”, said Woods, and Witton added, “I think it’s the kind of thing that moves with [the audience]“.

Woods admitted that she wasn’t massively familiar with the play before this production. “What was nice is that so many people have come up to me and told me it’s their favorite play, which is really exciting. And I haven’t seen a lot of versions of A Doll’s House, so it is quite fresh”. I asked her if she had seen it staged. “No!” exclaimed Woods, “and I’ve purposely not watched it on YouTube or anything like that”.

Though Henfrey pointed out that he and Woods are keen to stage the play as a period piece, arguing that the language doesn’t work in a contemporary setting, there is an engaging, easy naturalism about the way the actors inhabit their roles. Torvald and Nora each, in turn, can seem like repellent figures: Torvald for his narcissism and his saccharine, paternalistic attitude toward his wife and Nora for abandoning her children as well as her husband – the act that led the play to be banned in its original form in the United Kingdom. Witton and Gillespie deserve major props for the way they’ve invested these characters with a really believable chemistry.

“[Nora] has not had that chance at all”, said Witton, when I asked about the pair’s attempts at self-invention. “It’s just funny because she gets to the end of this play, she makes this decision to leave everything she’s known – at the beginning she’s so childish because she is a child, she’s never had a chance to find out who she is as a person, she’s been passed from one hand to another”. Nora, whether a “songbird”, as Torvald puts it, or a “doll in a doll’s house”, as she finally declares at the play’s climax, has been denied the tools we craft identity with. “I think this play is analysing the advance of individualism – liberal modernity coming in”, suggested Gillespie. Listening to the actors reflect on their roles, A Doll’s House almost seems, for a moment, like Ex Machina or Pinocchio – stories about a machine becoming a man, or, more pointedly, a woman.

A Doll’s House is showing from 29th November to 1st December at the Howard Theatre, Downing College.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025

Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025