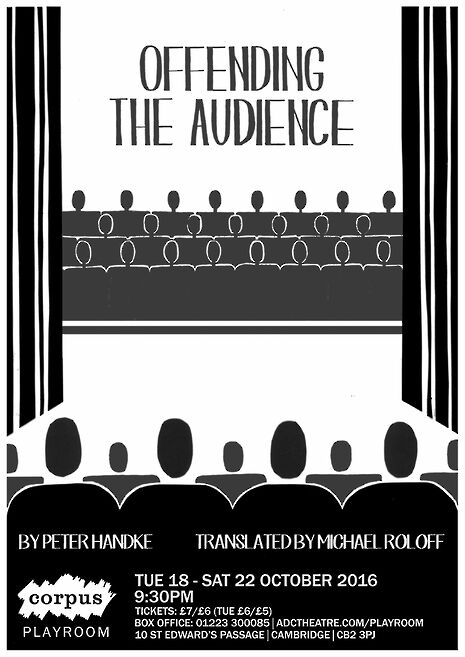

Review: Offending the Audience

Vanessa Braganza is neither offended nor overwhelmingly entertained by Corpus Playroom’s production of Offending the Audience

How does one review a play that repeatedly insists it is not a play? Faced with this singular dilemma, I have little choice but to take the Corpus Playroom’s recent production of Offending the Audience, directed by Zephyr Brüggen, as nothing more or less than what it claims to be:

It is not a spectacle – it is not a representation – its stage is not a world, just as the world is not a stage.

All these things you are told as soon as you step into the theatre. This is a production that repeatedly defines itself by negation. Repeatedly. For a good hour, its Spartan cast of three (Ellen McGrath, Carine Valarche, and Andreas Bedorf) stands at close quarters to the audience in the tiny auditorium (which, for their purposes, conveniently lacks a stage), and insists that they are not playing characters. They speak in a symphony of incantatory objections throughout, their speech weaving in and out of each other’s: this is not a play. Time is not suspended as in a fictional dramatic universe. They assert that there is no plot or narrative. One has a sense that there is no script either, for at several highly awkward moments the performers either hesitate or utter what appears to be the wrong line.

But, as the play would have it, this is precisely the point. It is not supposed to consist of artifice – in fact, it is not really a performance at all. Its avant-garde anti-theatricality shatters the fourth wall, rendering the audience exposed and vulnerable. The ‘actors’ talk directly to the audience, making disconcertingly direct eye contact and drawing attention to their every move – their breathing, their blinking – while another anonymous performer walks a handheld camera down the aisles, projecting live video images of each audience member onto two large screens. The self-consciousness each audience member feels is probably not unlike the way an actor feels onstage, with all eyes on him.

We are suddenly aware of the expectations we unconsciously bring to the theatre, our unspoken assumptions of plot and audience anonymity, precisely because this ‘anti-play’ subverts them. The performance jarringly levels and partially inverts the player-audience hierarchy of traditional drama: the audience, the speakers repeatedly assert, is the subject.

But the play never delivers on this promise. The performers never exploit the infinite possibilities inherent in breaking down the constraints of performativity. While they make it amply clear that they are dissolving the invisible barrier between performers and audience, they never actually reach through the ruins of the fourth wall to make onstage and off-stage universes interact in a significant way – except to invite the audience ‘onstage’ midway through the performance for crackers and pineapple juice.

The production climaxes with the performers donning clown masks and shouting profanities at an audience wearied by an hour’s repetition of the same phrases. The play’s title seems rather misleading. By the time the performance ends, your sense of being an audience member has undergone a ruthless Derridean deconstruction. But neither are you particularly offended. The obscenities screamed by the performers, along with their recursive monologues, have a numbing effect and are stripped of any shock value they might have held by the already iconoclastic nature of the performance. Its senseless sound and fury is somewhat amusingly reminiscent of Macbeth: everything you might see and hear simply “signifies nothing.”

Ultimately, Offending the Audience devolves into Waiting for Godot. The audience is left with a sense of anticipation and possibility – a feeling that something significant is about to happen – that is never fulfilled. The play is, essentially, anticlimactic. Its deployment of repeated formulaic phrases gives the overwhelming sense of a broken record that never quite manages to move past the skipping point. Moreover, the potential to co-opt the audience into the performance, emphasised throughout by the actors, is never realised. Anything could transpire, but nothing does, despite some of the interesting conceptual elements of the work.

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026 Arts / Fact-checking R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis13 January 2026

Arts / Fact-checking R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis13 January 2026 News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026

News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026 News / SU sabbs join calls condemning Israeli attack on West Bank university13 January 2026

News / SU sabbs join calls condemning Israeli attack on West Bank university13 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026