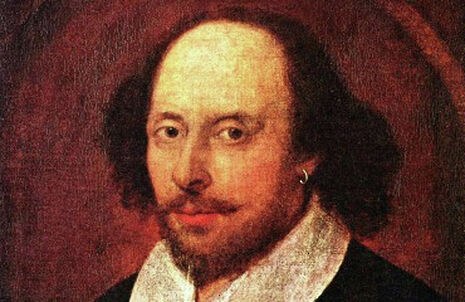

Shakespeare Revisited

In light of the bard’s 400th anniversary, Charlotte Taylor analyses what makes Shakespeare so timeless

The 23rd of April marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, and of course it is being commemorated with suitable theatrical aplomb – the BBC promises a lavish live celebration, and productions of Shakespeare will no doubt be even more ubiquitous than before. It is a curious event to celebrate in many ways, and not one most people would imagine as complimentary. But perhaps in the case of Shakespeare it is oddly appropriate: after all, this is the man who gave us some of the greatest reflections on death and mortality in any language.

To a certain extent, though, what we are really celebrating is that the man Shakespeare fell off his mortal coil and provided ample room for the myth of the boy from Stratford to enter centre stage. No sooner had he dotted the ‘I’ on his will than the legend of the provincial genius who goes to London and almost instantly makes good was embellished, crystallised and preserved for posterity. It is now impossible to call forth the flesh and bone of the man, and so the person ‘William Shakespeare’ has become a tenuous entity, whose very mortal existence has even been questioned.

But if Shakespeare the man is unrecognisable to us, then the modern productions of his works would have been equally unrecognisable to the man. For the past 400 years, we have happily taken a free reign with his texts: we have written a happy ending King Lear, cut the fifth act of The Merchant of Venice, transposed the action of plays across place and time and transformed the villains into victims. Most shockingly of all we have even deigned to let women speak his hallowed lines (the horror!), and all of this has been done with relatively little in the way of opposition or controversy. Perhaps if Shakespeare had survived as more than a Renaissance ideal, none of this would have happened – but perhaps he would not have endured.

In many ways it is Shakespeare’s illusiveness as a playwright that has sustained his legacy. After all, the play’s the thing, and he was pretty good at writing them. So what is it that distinguishes Shakespeare from the rest? Largely, it seems to be his openness. An ability to re-interpret is essential in the arts, particularly the theatre, which constantly has to reproduce itself, but there are plenty of plays and playwrights who produce a piece that simply stands for one viewing and then descends into immediate stagnation. This cannot be said to be true of Shakespeare. His works are not static entities that can be locked down to a particular interpretation: instead, they are multi-layered, textured pieces that demand constant re-appraisal and originality. As the man has descended into myth, he is more able than ever to remain a disinterested shadowy presence in a production rather than someone table-thumping his view. But this is only possible because the man himself made the myth through the mercuriality of his own works.

Perhaps the clearest indication of this openness is in the presentation of his work. In a period when Hollywood has had to face up to its own issues with representation, it is easy to overlook the how the works of the Bard have always been used to examine questions of race and gender, frequently against hostile political backdrops. In 1825, Ira Albright was the first black actor to play Othello, in a production that was brought to a standstill by the slavery lobby. Since then, the race of actors has mattered less, with David Oyelowo being the first black actor to be cast as one of the Bard’s kings by the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Shakespeare’s own interest in playing with gender and identity have also made his works natural territory for more explicit examinations of the issues. Last year, Harriet Walter played Henry IV following her successful turn as Brutus in an all-female production of Julius Caesar set in a prison. Shakespeare has come a long way from being a boys-only club! But these explorations of the issues are only possible because they use his texts. Shakespeare remains the single most-performed playwright in the world, and his plays have seeped into humanity’s consciousness in a way that is without parallel. Almost anyone can recite the plot of Romeo and Juliet without ever having seen or read it, so an audience can immediately see the significance of swapped genders or a role reversal. Through his own generosity Shakespeare has become more than a playwright: he has become a recognisable human voice for everyone to exploit.

400 years of popularity constitute an impressive feat to celebrate, and in that time Shakespeare has evolved from man to myth to a collective voice for humanity. We shall never be able to know the man who died in Stratford four centuries ago, but that should not be our concern. This is perhaps the most fitting moment to revisit his works and reconsider our initial renderings because this is what his death allowed us to do: re-interpret.

Features / Meet the Cambridge students whose names live up to their degree9 September 2025

Features / Meet the Cambridge students whose names live up to their degree9 September 2025 News / Student group condemns Biomedical Campus for ‘endorsing pseudoscience’10 September 2025

News / Student group condemns Biomedical Campus for ‘endorsing pseudoscience’10 September 2025 News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025

News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025 News / New left-wing student society claims Corbyn support11 September 2025

News / New left-wing student society claims Corbyn support11 September 2025 Science / Who gets to stay cool in Cambridge?7 September 2025

Science / Who gets to stay cool in Cambridge?7 September 2025