Political football? Everyone’s at it

FIFA may try to deny it, says Percy Burton Preston, but football and politics cannot be separated

Politics has no place in football.

But try telling that to a politician on the hunt for votes: for them, football’s popularity is too enticing a prospect to pass up. Yet, in the end, as all fans know, football can be a cruel game.

In a speech delivered on the South London stop of the Conservative Party’s general election campaign trail, David Cameron scored an own goal: he forgot which team he supports. Imploring members of his audience to support West Ham, Cameron apparently failed to remember that he, in fact, claims to be an Aston Villa fan. Later he cleared up any confusion: he was suffering from that well-known politicians’ affliction: ‘brain fade’.

Politicians using football to generate popularity is nearly always disingenuous, and often embarrassing. Yet, aside from offering a case study of political insincerity, Cameron’s mistake highlights something more essential about football in the 21st (and perhaps any other) century: it is, unavoidably, political. As much as fans, players and those involved in the game in any other capacity might squirm at what this might mean, it is an inevitable consequence of the fact that the sport attracts such a large global fan base and even larger amounts of money.

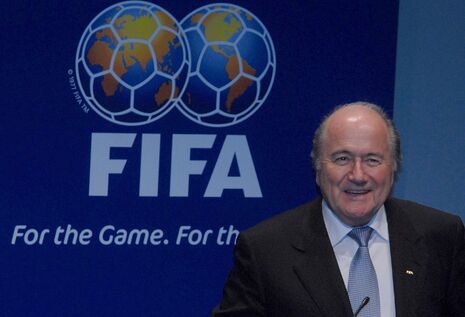

But it is a truth repeatedly rejected by those at the very top of the global game’s governance. In September of last year, the disgraced former UEFA Secretary Michel Platini gave assurances to the Associated Press that if he were to become FIFA president, his presidency would be “about football, not politics”. And Platini’s stance is hardly unusual among FIFA officials: the former president himself, Sepp Blatter – like Platini currently suspended from footballing activity – has repeatedly rejected the idea that football and politics can, should, or even do mix.

Yet Blatter’s rhetoric is at odds with the events of his presidential tenure, the final few years of which saw an FBI investigation into the awarding of two World Cups, repeated allegations of bribery and extortion against senior FIFA members and condemnation by Amnesty International over the treatment of migrant workers in Qatar. FIFA has also sought changes to local law in Qatar that would allow for the drinking of alcohol in designated public areas: a move designed to please sponsors, but one with considerable political implications.

The question, then, is not whether football should be political. It clearly is. The question is why the opposite is so ardently asserted.

Platini, like Blatter, might argue that football ought to be a space divorced from external, and specifically political, pressures. And this is an attractive rationalisation: one of football’s great joys is that it offers a refuge from these concerns, for players and fans alike. Yet this rationale hides a more pernicious reality, as it implicitly absolves those involved in football of any political responsibility. It perpetuates the belief that football’s problems are not political issues. Instead, the most pressing concerns confronting football’s governing bodies are the use of goal-line technology, or changes to the offside rule.

Ironically, it is precisely this thinking that sees football repeatedly embroiled in political scandal. Decisions like those to award consecutive World Cups to Russia and Qatar can be justified on the basis that FIFA does not involve itself with politics when choosing host venues for their tournaments. Deliberating over factors such as a country’s human rights record, for example, would be a little too close to politics for the comfort of many at FIFA. (If accusations are to be believed, FIFA relies on more impartial and empirically robust measures to elect a host a nation, for example, an association’s capacity to bribe FIFA officials.)

FIFA’s attempts to defer moral and political responsibility do little for migrant workers in Qatar, nor for LGBT+ people in Russia. And while FIFA can hardly be held responsible for the latter’s struggles in particular, awarding the World Cup to these nations confers all the legitimacy and cultural cache that inevitably comes with the one of the most prestigious sporting competitions in the world. Whether FIFA likes it or not, ownership of the World Cup comes with considerable political responsibility.

Indeed, it is perhaps FIFA that stands to lose the most from the false division of politics and football. By repeatedly embroiling itself in political controversy, often as a direct result of its pretence of impartiality, FIFA will become the architect of its own irrelevance. At least with insignificance might come the possibility of political neutrality.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026

News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025