Simon Kuper: ‘Guts are much more likely to mislead than data’

Paul Hyland talks statistics, signings and Sam Allardyce with Financial Times’ renowned Soccernomicist

It seems like lifetimes ago that Leeds United were among England’s top dogs. Champions of England in 1992, the Yorkshire club finished in the Premier League’s top five every year from 1998 to 2002, and were narrowly defeated by Valencia in the 2001 Champions League semi-final. But theirs is a story of economic brinkmanship that ended in relegation to the second tier in 2004: having floated the club on the London Stock Exchange in 1996, and raising an extra £35 million in share prices, they embarked on a period of immense spending and borrowing that became unsustainable. The club has not competed in the Premier League in 12 years.

“Pretty soon the shares were worth nothing at all,” says the Financial Times’ Simon Kuper, who credits moments like these with his interest in the economics of football. “And so it was really from then that I began to think about football not just as a game but as an anthropological phenomenon, which I’d done before, but also as a kind of economic question.”

Kuper is best known for his most famous work, the 2009 Soccernomics, which aims to dispel so much of football’s received wisdom, with economics as a guide. Together with economist Stefan Szymanski, he showed that a new manager has little effect on his team’s chances, that football clubs should always be run at a loss when success is at stake, and that clubs who rely on gut instinct ahead of numbers are bound to suffer. “We began writing the book eight years ago when there were very few people of that kind working at clubs,” he remembers. “And now if you go to a club like Barcelona or Manchester City, there are loads of people like that. And some have read Soccernomics and a lot of them have been to business school. So that mode of thinking about football in, let’s say, a slightly more rational way, has become much more common, even among fans.”

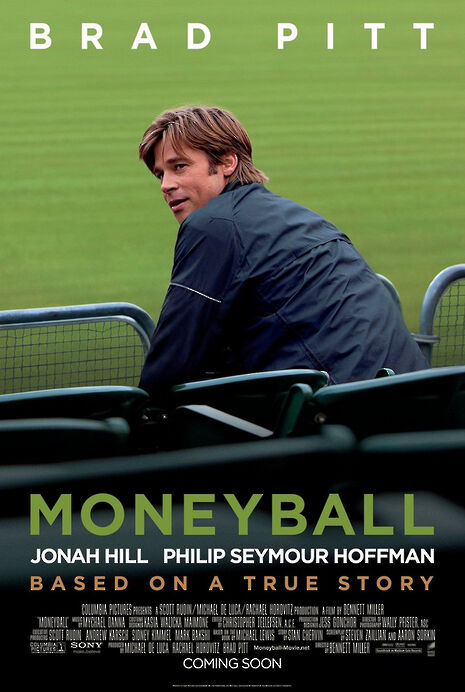

What kickstarted football’s own interest in mathematical analysis was Michael Lewis’s 2003 book, Moneyball. It followed perennially-unfancied American baseball outfit Oakland Atheletics, who played their way to a 20-game Major League Baseball winning streak, the longest in the sport’s history, thanks to manager Billy Beane’s statistical approach that could identify undervalued players. The Oakland A’s exploits inspired not only a Hollywood movie starring Brad Pitt, but a host of English football club owners hoping to game the system. Chief among them has been John Henry, principal owner of Liverpool Football Club.

As Kuper shows, some clubs are reaping the rewards far more than others. While stats had convinced Liverpool to justify a combined £55 million outlay on eventual flops Andy Carroll and Stewart Downing in 2011, they were helping to crown a new national champion five years later. “When Leicester signed Kanté and Mahrez, they wouldn’t have done it without the stats,” he argues. “Kanté, his stats were more about interceptions. And it seems that interceptions are a good stat for that kind of player, so we’re getting a better sense of what matters. And for Mahrez, who’s playing in the French Second Division, Leicester were actually using videos to create their own stats on what Mahrez was doing in matches.”

Kuper then says something that surprises me. Likeable Italian tinkerman Claudio Ranieri – whose dogged counter-attacking ethos became the hallmark of the Premiership's newest champions, Leicester City – was recognised this May as the League Managers Association and Premier League Manager of the Year. Though his peers recognise this most astonishing league title win as his own work, Kuper prefers the congratulations to go elsewhere. “I think it’s the whole staff at Leicester using data [that] has more to do with their success than Ranieri does, but to Ranieri's credit, he let it all happen and he obviously played a part in managing the staff. But stats are much bigger now than they used to be and they contribute a lot more than they used to.”

How stats could help in one case and hinder in another comes down to how they are put to use. “Downing was a very good crosser of the ball, and Andy Carroll was a very good header of crosses. But hitting high balls into the box and then heading them in is a very inefficient way to score. Downing and Carroll were probably the best people to do it, but it’s a really bad way to try to score goals because it’s very difficult. And so they were kind of betting on the wrong system. But I find it hard to blame them, because who knew all this six years ago?”

As our understanding of the relationship between football and data matures, the significance of the talismanic manager wanes. One such manager, often praised in Kuper’s work, is Arsène Wenger. Having failed to win the league title for 12 seasons now, Wenger’s apparent decline perfectly exemplifies how economics have come to underlie all of football’s key decisions. “If you think of how he got his best players – Vieira and Henry – you didn’t have to be a genius to see that Vieira was a good player, and he was on the bench at Milan. Nobody in England knew about him in 1996. Everyone’s out scouting now, whereas 20 years ago, Wenger was the only person scouting. He knew about scouting and diet, but now everybody does that. So he doesn’t really add any value anymore.”

Though Arsenal fans, increasingly calling for higher spending, and for Wenger’s head, might find themselves disappointed, Kuper’s research has found little correlation between spending on transfers and overall success. In fact, a team’s success correlates more strongly with their overall wage bill than any other factor – including their manager. With that in mind, it is hard to see how ousting Wenger could yield more of the kind of season Arsenal enjoyed in 2004.

So what is a team with the title on its mind to do? Counter-intuitively, holding onto the players they have is much more significant than buying new ones, as Kuper points out: “At Manchester United, they got these great young players in during the early ’90s, and they didn’t let anyone go until the players were past it. They paid them high wages, and they won everything. So my sense would be if you get a good player, to spend what it takes to retain him would be the smartest policy.”

Soccernomics also famously tries to answer the question that has plagued the national game for over 50 years: why do England always lose? Whereas English football bosses have gone as far as to introduce quotas in order to increase the number of English players playing in the Premier League, it argues that there are already far too many. Not enough English players test themselves abroad, therefore lacking access to innovations in coaching that generally take place – and are quickly shared – across the European mainland. Surely now the position of English football is more challenged than ever, with Britain voting to cut itself off from Europe, and England having hired yet another old-fashioned English manager?

Kuper recognises the impact that Brexit has had on the English game already, explaining that the mood around the country was such that the FA had to appoint an Englishman, “even if he seemed to be less qualified than a continental.” But Sam Allardyce, whose team laboured to a 1-0 victory at the death to Slovakia at the weekend, comes in for some unexpected praise. “One of the confusing things about him is that he looks like a neanderthal,” he laughs. “But in fact, he was someone who got interested in data forty years ago playing for Tampa Bay in America. He saw how American football and baseball were all about stats, and he loved that.

“So when he went to Bolton, this was a club that for many years had not been a stable top-division side. So they said, ‘We have to go for marginal gains, we have to use data.’ So people like Allardyce, Wenger or Ancelotti, most of the people at the top of the game today, they’re completely on board with this.”

As more and more clubs turn to statistics to get an edge on their opposition, I wonder what the future holds. What is the next big step in the future of football analytics? “Data are not yet that good at telling you about the game on the field,” Kuper says, “because the average player only has the ball for one minute. So what is he doing the other 89 minutes when he’s not touching the ball? It’s very hard for the data to tell you. But we are advancing every year in match data, and physical data are just completely being accepted by pretty much everyone. So I don't think you’d get many morons these days saying, ‘I don’t care what the data say, I know what my gut says.’”

But surely you do get it. Are there managers who still reject data, and opt for gut instinct instead? “Yes,” he admits. “But when they’re doing it right, without knowing it, they’re using data. If you say someone’s a big game player, you might be misled by one memory of one game. At Chelsea, the data showed that Michael Ballack didn’t go all out against the smaller clubs because he was very cannily saving himself. So the stats would show that he’s a big game player, but the manager’s guts might tell him the same thing. But the problem is that guts are much more likely to mislead than data.”

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025