Why do we get cancer?

Grace Ding explains the science behind the terrible disease

When I asked my friends studying arts subjects about their understanding of cancer, “a mutated cell” was a common response, beyond which they admitted knowing very little about the science behind the disease. The majority of cancerous tumours do indeed originate from a single mutant cell that, as a result of changes to its DNA known as ‘mutations’, has increased cell division and growth.

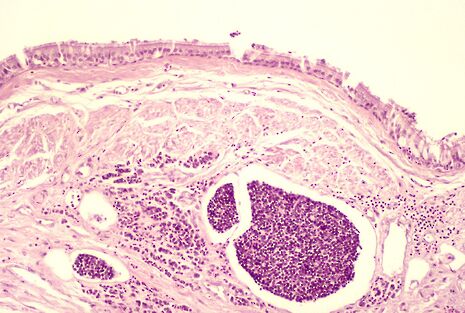

The simplest of mutations can arise during DNA replication, with a change in a single ‘letter’ of DNA’s four-letter code. A change in this sequence may result in a non-functional protein being produced when the cells ‘read’ the altered DNA code. If the affected protein is involved in regulating cell division, then this process can become uncontrolled, resulting in the cell dividing more often than it should. This leads to the development of a tumour. Tumours that can spread to surrounding tissues are classed as ‘malignant’.

Mutations occur frequently in our DNA; they are an unavoidable consequence of the limitations in the accuracy of our DNA replication mechanisms. It has been estimated that during a typical human lifetime, mutations will have occurred on 10 billion separate occasions in each of our genes. When confronted with a figure that large, it’s a wonder the incidence of cancer isn’t much higher. This is because, thankfully, most mutations are harmless and there is an extensive network of DNA checking and repair mechanisms in place to minimise the risk of harmful mutations remaining in the code. A cell can even commit suicide (a process known as apoptosis) when the DNA damage becomes too great to repair.

Tumours will only form following a very specific sequence of mutations; a single mutation alone is insufficient to cause a cancer. These mutations have to occur within sections of DNA that regulate cell proliferation. As mutations arise randomly, only a small minority of them are potentially cancerous. However, if we all lived for an infinite length of time, everyone would inevitably develop a cancer of some sort. DNA replication is not 100 per cent accurate and it is only a matter of time before a mistake occurs in a gene that regulates division and growth, and that’s why cancer is more widespread among the elderly.

Factors promoting the formation of mutations are known as ‘mutagens’, and many of these are also carcinogenic. Tobacco smoke, burnt toast and sunlight are all known to contain carcinogens. Prolonged or repeated exposure to these substances increases the risk of certain cancers as they induce changes that cause damage to DNA.

Intrinsic aspects of our bodily processes can also elevate the risk of cancer. Female reproductive hormones controlling cell proliferation in breast tissue have been linked to the development of breast cancer. Some of the most powerful carcinogens are chemically inert when they enter the body and are converted to a mutagenic form by metabolic processes. A common carcinogen activated in this way is benzoapyrene, one of the most dangerous chemicals in tobacco smoke.

Aside from lifestyle factors, our genetics also influence our susceptibility to specific cancers. Angelina Jolie opted for a double mastectomy after testing positive for a mutant form of the BRCA1 gene. Carriers of the mutant form of this gene will produce less or none of the protein aiding the repair of DNA damage. As a result, carriers will accumulate mutations more rapidly, significantly increasing their risk of developing certain cancers. Because we inherit our genes (including the potential for mutations) from our parents, our risk of developing certain types of cancer may depend upon which ethnic group we are born into, even once environmental and lifestyle factors have been taken into account.

In a way, cancer is a natural by-product of ageing, accelerated by various factors that are still not fully understood. But as populations worldwide continue to age rapidly, this complex disease will sadly become more common.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025