The recap theory of evolution

Anticipating backlash from the scientific world, Darwin accumulated support that went into On the Origin of Species. Aniket Patel investigates.

Most people have heard of Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution by means of natural selection. While this theory is widely accepted by the scientific community today, Darwin unsurprisingly faced widespread opposition when he first published his book, On the Origin of Species. He had anticipated this reaction and had accumulated support for his theory that he included in his book – one of these pieces of support was recapitulation theory.

Recapitulation theory, also known as the ‘biogenetic law’ or ‘embryological parallelism’, is best summarised in the words of the 19th century German scientist Ernst Haeckel: “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.” In plain terms, the development of an animal from an embryo to an adult mirrors the evolution of that animal. The concept is an ancient one, having been first formulated as a theory on the origin of language by the Egyptian Pharoah Psamtik I. Some Victorian evolutionists used the theory as evidence to promote the concept of evolution following the publication of Darwin’s book.

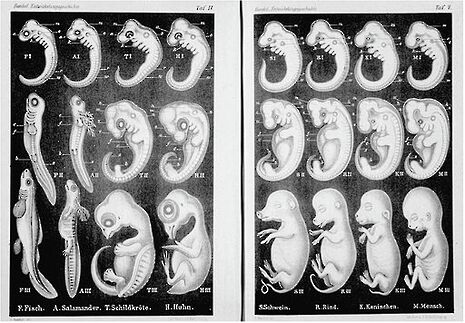

Haeckel was the most enthusiastic proponent of the theory. He claimed that each stage of an animal’s development represented the adult form of one of its evolutionary ancestors. He even went as far as to draw various diagrams of animal embryos at different stages of development to display how he believed they resembled one another, but he greatly exaggerated the similarities between the embryos in his drawings and was therefore accused by his contemporaries of distorting the images.

Darwin’s view of the theory was slightly different from Haeckel’s. He believed that the certain embryonic stages of a species resembled the corresponding embryonic stages of related species, as opposed to their adult forms as Haeckel advocated. Darwin’s view has since been confirmed by modern evolutionary developmental biologists.

Evolutionary developmental biology is a relatively new science that views evolution as the result of changes in development. When Darwin was writing On the Origin of Species, he consulted his friend and fellow biologist Thomas Huxley about the origins of variation. Huxley told Darwin that the variation between species was due to differences in their development and that these differences “result not so much of the development of new parts as of the modification of parts already existing and common to both the divergent types.”

This is one of the key concepts behind evolutionary developmental biology: if development is the change of gene expression and cell position over time, then evolution is the change of development over time. Indeed, altered embryological structures would give rise to altered structures in the adult, which could confer an evolutionary advantage to an organism. Changes in adult organisms that confer evolutionary advantages result from changes in the embryological structures, meaning that the traits that natural selection selects come from different traits in the womb.

Although embryological development may not exactly mirror the evolution of a species as Haeckel believed, and whether or not developmental changes are the driving factors behind evolution itself, one thing cannot be denied: certain features found in embryos of various species are similar to and homologous with features found in the embryos or adult forms of animals in different species, and therefore share a common source.

A good example is the branchial arch artery system in fish compared with the human circulatory system. The fish’s system consists of one ventral (bottom, near the fish’s belly) aorta and two dorsal (top, near the fish’s back) aortas running along the front of a fish’s body. Aortas are the primary large arteries that carry oxygenated blood away from the heart. The dorsal and ventral aortas are connected by a series of arched arteries, which run alongside the gills of the fish to carry out gas exchange with the water. In humans, a similar system forms, but is remodelled during development to form part of the circulation as it exists in the adult. The aortic arch arteries must therefore have evolved from a common evolutionary ancestor of both humans and modern fish.

While the recapitulation theory is today considered redundant in its Haeckelian form by most of the scientific community, embryos do go through a period where their development closely resembles their evolutionary ancestry. While much of the science of evolution remains shrouded in mystery, the links between development and evolution are incontrovertible.

Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026

Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026 Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026 Theatre / The ETG’s Comedy of Errors is flawless21 January 2026

Theatre / The ETG’s Comedy of Errors is flawless21 January 2026 News / Write for Varsity this Lent16 January 2026

News / Write for Varsity this Lent16 January 2026 News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026