Cambridge research drives progress in understanding hearing loss

Cambridge research suggests cognitive training exercises might be a way to combat age-related hearing loss

A recent study has found that the difficulty in understanding speech faced by the older population is not just due to peripheral hearing loss. The study, which was a joint venture by hearing scientists at the University of Cambridge and the MRC Institute of Hearing Research in Nottingham, points to problems with cognitive skills and central auditory processing as significant contributors in age-related difficulties in speech understanding.

People with a hearing impairment report a lower quality of life than those with unimpaired hearing, as well as higher levels of depression and social isolation. Almost all older people experience some level of hearing loss, making this a widespread condition. Dr Christian Füllgrabe, who led the research, said, “Speech communication difficulties not only constitute a social and psychological challenge for the affected person but also represent an important financial burden for society in terms of healthcare provision”.

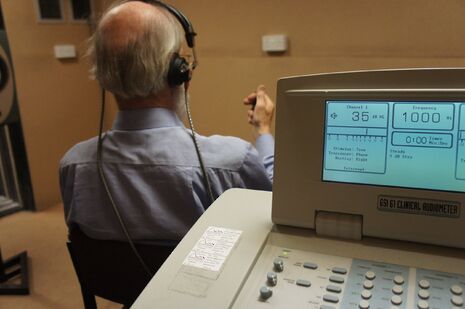

Clinical diagnosis of hearing loss has traditionally been confined to measuring peripheral hearing sensitivity, or the quietest sounds that a patient’s ear can detect. The usual treatment for peripheral hearing loss is a digital hearing aid, which amplifies sound level, restoring audibility of sounds that had been too quiet to hear.

The researchers performed speech-in-noise tasks that measure a listener’s ability to understand sentences in the presence of background speech – a common, everyday challenge that becomes more difficult with age. But the age-related deterioration in detection of quiet sounds does not account for the full extent of the decline in speech intelligibility. More central processes may be at work.

This discovery has been complicated and delayed by the fact that almost all older people have peripheral hearing loss. Lacking older participants who could still hear sound at low levels, the effects of aging on central processes and peripheral hearing sensitivity could not be separated. Previous research resorted to lax and less stringent inclusion criteria. In the new study, younger and older participants were well matched in terms of peripheral hearing sensitivity. “It took a long time – several years – and required targeted recruitment campaigns to establish our sample of older normal-hearing participants,” said Dr Füllgrabe.

The researchers found that the older participants without peripheral hearing impairment struggled on the speech-in-noise tasks more than young participants, even though both groups could hear sounds at the same level. This provides conclusive evidence that age-related decline in speech intelligibility occurs even when the ability to hear quiet sounds is normal.

The best predictor of the ability to understand sentences, heard concurrently with other speech, was cognitive function – including memory, attention and processing speed – and, to a lesser extent, central auditory processing. Both of these functions commonly decline with age. This means that, in addition to hearing aids, older people with hearing loss may benefit from cognitive and perceptual training programmes.

The research team is now studying normal-hearing participants aged from their teens to their nineties. They hope to discover the point during adulthood at which these age-related changes can first be observed and if there is a causal link between sensory deficits and cognitive decline.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025