Spotlight On: Cross-discipline research in Earth Sciences

Varsity sits down with the head of the Department of Earth Sciences to discuss the growing interdisciplinary nature of research, and other issues facing modern science

Earth Sciences is an exciting field that has undergone a revolution in recent years. I spoke to Professor Simon Redfern, Head of Department of Earth Sciences, to find out more about what Earth Sciences really is and the research being undertaken in Cambridge.

“Earth Sciences is the study and understanding of the Earth as a planet. The Earth is a living thing that is changing with time. We take the Earth as our example as it’s the one we have most data for, allowing us to understand how you make a planet, and what’s going on in a planet. It’s a broad field that encompasses everything from understanding early Solar System formation, all the way through to understanding changes in the global climate that we see today,” he explains.

There’s a broad range of research being undertaken within Earth Sciences, from its biological side in understanding the origin of life and its evolution through fossil analysis, to its chemical side comparing earth chemistry to that of the rest of the Solar System: “a lot of the information explaining phenomena such as how continents have changed through time, and how the moon formed has come from understanding the chemistry within rocks.”

Physics is also integral: “there’s a large geophysics group, who are finding out about the physics of the solid Earth as a physical entity, understanding the mechanics behind its faults and fractures.” There’s also considerable work being done, including by Professor Redfern himself, on the Material Science of the planet – “from what goes on in the core where the pressure is three million atmospheres [and] temperatures are 6000 kelvin, through to how organisms in oceans grow their shells as a biomineral”.

It is its interdisciplinary nature that allows Earth Sciences to answer some of the most difficult of life’s questions. “What’s become clear in the last couple of decades is that what were regarded as separate disciplines within the sciences are very much interlinked. For example the evolution of life on Earth is related to the atmosphere; the atmosphere is related to what goes on in the solid earth.”

The research that takes place at Cambridge is itself carried out across the globe, both in terms of fieldwork and work in laboratories, deploying cutting edge analytical devices and computer simulations. Yet there are many questions still unanswered, some of which are being solved by undergraduate students themselves: “Part III projects are real research projects that are addressing questions that no one else has thought about previously.”

In addition, Earth Sciences is one of the departments leading the way on addressing gender imbalances within the sciences. “Athena Swan is a national scheme that is focused on tackling issues of equality and diversity in science, with a focus on real and perceived issues surrounding career trajectories of women in science,” he explains.

This imbalance can be observed when you look at senior career-levels, where women are much less well represented. The “leaky pipeline”, Redfern calls it. “Women don’t progress through their scientific career in the same way as men, as women seem to not pass through the stage of securing a permanent position.” What Athena Swan is attempting to do is “address this issue by changing the way we think about things”. It aims to “develop a level playing field for everybody”.

In recent years, there has been a drive towards ‘impact’-driven research, cemented by the introduction of the Research Excellence Framework. Although the intention of this is to ensure the research being done will have positive impacts for ordinary people in the real world, Redfern explains that the more “esoteric aspects of our research” are less able to meet this criterion.

“It’s the aspect of discovery that excites many of us. That’s why we want to do science in the first place. Aside from that, there are aspects of what we do that really benefit society in many ways.” For example, the team’s work on earthquake dynamics is having far-reaching and life-saving effects, which stretches beyond just the science, “developing an awareness in the local communities of the risks”. They also advise on policy related to resource management and climate change: “as scientists, we observe what has happened in the past so we know for example that the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere today is greater than it has been for the last 10,000 years.”

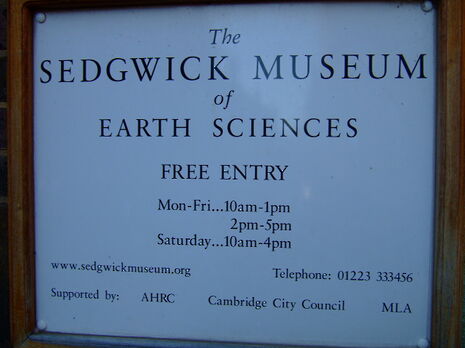

It is important that this cutting-edge research radiate out of the academic sphere into the wider community, so that global citizens have an awareness of what is being done to tackle some of the 21st century’s greatest problems. “I feel like, as scientists, unless the public know what we are doing, we lose our license to operate. There is the Sedgwick Museum which has a huge amount of outreach to schools and the local community. Also, I have worked as a British Science Association media fellow, producing articles for the BBC and other outlets.”

But Redfern notes that it must work both ways. “It’s also important to ensure that policy makers understand scientific evidence, so a lot of what we do is to provide evidence to select committees, to the policy offices in departments in the civil service in areas in which we have expertise, so they can use these expertise to help the nation.”

Clearly, Earth Sciences is a broad multidisciplinary field with wide- and far-reaching impacts. It will continue to play an integral role in informing policy in future natural disasters, as well as in opening our eyes to the complex and incredible workings of our planet

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024

Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024 Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024

Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024