How could Brexit affect Cambridge science?

There are large ramifications for scientific research, investment and development should the UK vote to leave the EU

On Thursday 23rd June the UK will vote to either remain or leave the EU. There is continuous debate about whether or not a ‘Brexit’ would benefit the UK. Arguments for remaining focus on historical, geopolitical and economic concerns, while those for leaving express concerns on immigration and EU laws and regulations. However, a seldom-discussed topic is the effect of a Brexit on UK science.

The UK is involved in a pan-European research network which enables collaboration, as well as numerous sources of funding. Each year we receive almost £1 billion to invest in research, development and innovation. This is 16 per cent of the total available, making it the second-highest funded nation, just behind Germany, who receive 17 per cent. This is a significant sum of money that the UK could not afford to lose out on in the event of a Brexit.

The UK is the fifth-largest producer of scientific and journal articles behind the USA, China, Japan and Germany. However, there is only a small investment of 1.63 per cent from the public and private sectors in research, making it 20th internationally in R&D spend as a percentage of GDP. This means there is insufficient investment from the government, and EU funding has been used to cover up issues with how we choose to fund UK research both at a government and corporate level. In the event of a Brexit, there would be less funding available, and, needless to say, less funding will mean less research. This, in turn, means fewer papers being published by the UK, unless we find another means of funding.

In the event of a Brexit, it does not necessarily mean that science would have to be funded by an unpopular increase in taxes, as the UK would be saving the rather hefty membership fee of £13 billion. However, even the most optimistic economists expect a loss in GDP, and this will mean a loss in the science budget, regardless of how we spend the money we save on membership. Not all funding is restricted to the UK, but the funding available to non-member states is very small in comparison – currently only 7.2 per cent, the majority of which goes to Switzerland and Norway. In addition to this, the UK would have no say in shaping EU research funding.

A large proportion of the scientists currently working in the UK in labs for academia and industry are EU nationals, and remaining in the EU would be a welcoming prospect. However, in the event of leaving, many may prefer to move elsewhere in Europe.

For non-EU states, there are already strict visa regulations and so many may prefer a Schengen visa allowing fewer restrictions between borders. Hence we could easily lose some of UK’s top scientists.

Being in the EU aids collaboration and prevents national boundaries from restricting research. The Open Access and Open Data movements, for example, have different legal requirements in different countries. Funders wishing to ensure that data and publications are openly available may come across hurdles due to competing requirements between different countries. The EU’s funding criteria take account of this and foster relationships between different member states, but science papers from the UK could be easily sidelined without sustained funding to support travel and collaboration.

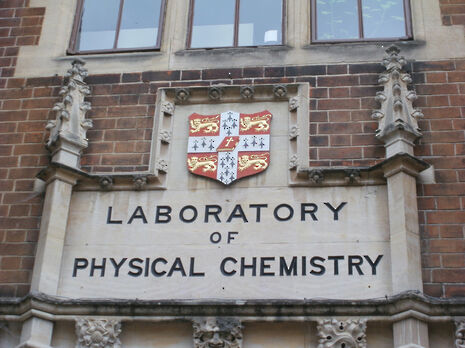

Within the UK, the highest dependency on funding is Southwest England, Outer London and parts of North England and Scotland, although the entire UK would be affected. Furthermore, different areas of science would be affected by different amounts. Evolutionary biology currently receives 67 per cent of their funding from the EU, nanotechnology receives 62 per cent and biomedical research receives just over 40 per cent. However, the funding for social sciences is greater; for example, economic theory receives a whopping 94 per cent of its funding from the EU. This would have an effect on universities since these are some of the leading institutions in research. The University of Cambridge is one of the biggest recipient universities, with 20 per cent of its research body funding coming from the EU’s eighth Framework Programme, Horizon 2020.

The impact of a Brexit on science is not entirely hypothetical, but can be compared with Switzerland’s relationship with the EU science programme. Switzerland had full access to Framework Programmes as part of an agreement that allows free movement of persons, contributing to their budget alongside other EU members.

However, after a vote to limit mass migration, Switzerland was no longer in accordance with free movement, and was thus suspended from Horizon 2020. This forced them to hastily produce a national scheme to replicate it. Should the UK leave the EU and restrict freedom of movement, it will no longer have access to Horizon 2020 beyond third-country status.

The UK would also have to pay into Horizon 2020 via a continued EU budget contribution. In the event of a Brexit, it is unlikely that politicians would agree on the free movement of people, and it is also unclear if the UK would still want to pay for Horizon 2020, as the fee is partially dependent on the population of the country.

We cannot predict the future and cannot say exactly what the effect will be on science. However, Brexit would cut a significant amount of funding, especially to research-heavy institutions like the University of Cambridge.

Much like uncertainty being the recipe for an economic crisis, a scientific funding disaster due to fluctuating and insecure support would be as likely and could ultimately prove to be damaging to Britain’s role as a world leader in research.

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025 News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025

News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025 News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025

News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025 Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025

Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025 Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025

Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025