The death of Cambridge’s anti-medicine cult?

Science Editor Jon Wall investigates the Christian Science movement

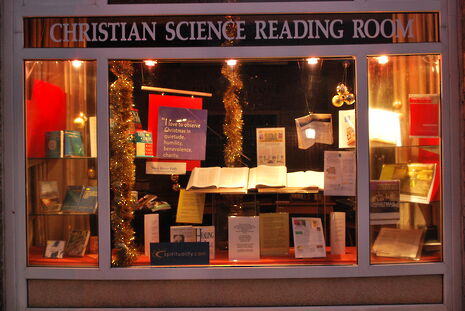

Along the series of shop fronts on Regent Street heading out of town, there are a few which stand out: Pizza Hut and Nanna Mexico, for example. As we continue past Downing College, though, the shops get smaller and more niche. It’s easy to miss the Christian Science reading room, a space smaller than a John’s accommodation room, yet many of us pass it by unthinkingly every day – and why not? It’s a harmless little place, empty the vast majority of the time, and only open three days a week.

However, the Christian Science movement as a whole is harder to dismiss. In Cambridge, the movement has repurposed an old Methodist church near the Botanic Gardens, and as well as the town centre reading room, there is a research library in nearby Elmdon. Cambridge, though, is relatively small fry as far as Christian Science is concerned. The movement is largely US-based, with headquarters in Boston – and it is here that the movement’s origins and major controversies lie.

Christian Science was the brainchild of Mary Baker Eddy, a widow from New Hampshire, and came into being in the mid-19th century, at the same time as Mormonism – a religion with which it shared a number of similarities, not least in being deemed by mainstream Christianity as a ‘cult’. The unique selling point of Christian Science was – and still is – that Mary Baker Eddy had discovered a new ‘Divine Science’ which constituted a return to primitive Christianity and emphasised healing.

She documented this revelation in Christian Science’s central text, Science and Health, which outlined how healing could be accomplished: through prayer. This had two major implications: firstly, in a spiritual sense, Christian Science prayer involves a struggle to realise the metaphysical truth that this world is essentially illusory compared to God. As such, Science and Health teaches that there is nothing to be healed but the soul.

This prohibits Christian Scientists from using doctors – if all that needs to be healed is the soul, why are physical remedies needed? In fact, Christian Science teachings suggest that healing is more effective when medical professionals are not involved at all, instead relying on Christian Science practitioners, who essentially pray for the sufferer.

This, naturally, has led to a series of controversies, particularly in the United States, by virtue of the larger Christian Science population there. A series of child deaths from preventable causes such as diabetes and meningitis led to an increased drive against ‘religious freedom’ standing in the way of caring for children, and several convictions of Christian Science parents for manslaughter.

While other minority religious groups with similar views on modern medicine have had members face jail sentences, however, Christian Scientists have been largely protected, due to the foresight shown by some of their members. Christian Scientists had tended to be middle-class and aspirational, playing prominent roles in government. Two of Richard Nixon’s most trusted advisors were Christian Scientists who successfully introduced a series of pieces of legislation giving the movement exemptions from important medical policies such as mandatory vaccinations.

However, in the wake of increasing legal scrutiny, the movement now insists that its members follow local laws – even though these may contradict its core teachings. I spoke further about this with David Willman, the organiser of Cambridge University’s Christian Science group.

He said that Mary Baker Eddy’s teachings in fact appreciated the work of medical professionals, suggesting that they were positive influences on her life, though he still maintains that healing is most effective without the influence of modern medical treatments. He also spoke to me about his personal, documented experiences of Christian Science healing, citing several examples. These included an incident when he was hit by a squash ball in the eye, went temporarily blind, yet following a minute’s prayer was completely “healed”. He offered a further example of an occasion when a painful lump or growth under his left arm vanished after a period of prayer.

While backed up by the Church, these ‘healing events’, as far as I am aware, have not been fully investigated or corroborated by medical professionals. The Christian Science movement as a whole relies on verified anecdotal accounts of healing such as these, published regularly in the movement’s journals, in order to make its claims for healing. These anecdotal claims are extremely vulnerable to false positives and mis-characterisation, and are not confirmed by outside sources as a matter of course.

All of this begs the question: if we have little good evidence for the healing powers of Christian Science prayer, and thus their particular view of the world, why is this religion popular? The simple answer is that it isn’t – at least, not any more. The Cambridge congregation is relatively small, and positively tiny within the University. David Willman suggests that there are single-digit numbers of Christian Scientists across the University – including just one undergraduate.

David himself is a retired academic, his age typical of many Christian Scientists. Globally, at least a third of Church members are aged over 65, frequently living together in clumps of retirement communities. This is a significant contrast compared to the early half of the 20th century, when the movement experienced a peak of around 300,000 active members in the mid-1930s. Today, the Church stands at fewer than 100,000.

There are a number of reasons for this. Early Christian Scientists were mainly women, drawn by the increase in career opportunities which the movement offered. As these opportunities became mainstream, the movement declined. Christian Science also – unlike Mormonism – does not use missionaries to spread the religion, leading to low conversion rates, even within families of Christian Scientists.

However, the most significant reason is advances in medical care. While in the past prayer may have been as effective as the dubious remedies of 19th-century doctors, discoveries such as antibiotics and breakthroughs in the understanding of diseases meant that Christian Science became substantially less effective. As such, it is hard to see a future for the movement. The growing age of its members means that this religion will likely eventually die out, with its healing methods increasingly discredited.

Given the number of people, particularly children, who have suffered from preventable illnesses because of the movement’s teachings, I’d have to say that this is no bad thing.

Frequently unnoticed, Cambridge’s small Christian Science reading room and community may soon fade into the city’s history

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Arts / Modern Modernist Centenary: T. S. Eliot13 December 2025

Arts / Modern Modernist Centenary: T. S. Eliot13 December 2025