Tackling gender inequality in science: a model that works

A look at what is being done in the Biochemistry Department to combat discrimination

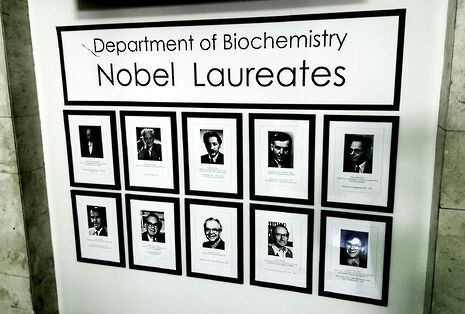

The Biochemistry Department’s Haynes room is littered with old portraits and leather-bound books, a common scene for a university seminar room. This room is, however, set apart by one crucial difference – all the portraits are of women. While Cambridge colleges and departments love to display their history in oil painting and sepia tone photographs, they rarely feature female faces, instead demonstrating centuries of male Masters and academics, who may, on rare occasions, be accompanied in their portrait by their wife. The aim of the Haynes room is to actively counter this, taking a stand against the male-dominated spaces that have been a major part of Cambridge past and present, and highlighting the contributions that women have made to the university.

This attitude is characteristic of the Biochemistry Department’s Equality and Diversity (E&D) committee, which exists to tackle discrimination of all forms. While the E&D committee is relatively new, the department previously had an active Athena Swan group, working under the Athena Swan charter to address gender inequality in science. The department has made significant progress within the Athena Swan programme and the change to an Equality and Diversity committee reflects efforts across the university to challenge all forms of inequality.

It aims to better acknowledge the diversity of factors feeding into personal, institutional, and systemic discrimination. And inequality is certainly present at every level in academia, from early education to research. Only 15.4 per cent of Cambridge University STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Medicine and Mathematics) lecturers are women, as are just 36.8 per cent of STEMM undergraduate students accepted in 2014. It was only in 1972 that Churchill, known for its strength in the sciences, admitted its first women students. With such gender disparity, both historic and current, making the university and its departments a safe, fair, and inclusive space for women is an ongoing battle.

The E&D committee includes academics and administrators from across the department to provide a voice for all, with a total of 17 members, including the Head of Department. The co-chairs are Julie Boucher – the Deputy Departmental Administrator, and Dr Dee Sadden – a research group leader who lectures undergraduates while also specialising in the field of RNA editing. They consider it the committee’s role to make certain “the department does everything it can to ensure there is no discrimination, and to create an inclusive working environment.”

The Equality and Diversity Committee are approaching the issue from a number of angles. Career progression was long seen as the major obstacle facing women in academia. The committee is trying to take a holistic approach to this, and address not only structural inequality, but also working space and practices. The department now has rooms equipped for breastfeeding and recreation; there are kitchen facilities for individuals working non-standard hours, and it has worked to improve the flexibility of working and meeting hours to better accommodate researchers with families. The department organises surveys and meetings with the academic and administrative bodies to highlight specific problems in the department that the committee can address.

Department members are encouraged to attend university-wide seminars and courses that aim to raise awareness about issues surrounding equality and diversity. For example, a number of department members recently attended a course on unconscious bias, which introduced various ideas for how to minimise the possibility of decisions being made with unconscious bias. For instance, a more impartial hiring system could be implemented, where information irrelevant to the candidate’s appointment (e.g. gender, ethnicity) could be withheld to ensure a fairer selection process. The number of women in decision making positions has also increased thanks to the committee, and a mentoring scheme is in place to provide both role models and a support network for female post-doctoral workers.

The Haynes room is a clear indicator of the department’s commitment to tackling gender discrimination. Nevertheless, the majority of the women in the pictures are white, another trend evident in Cambridge’s art collections, reflecting the lack of diversity that characterises much of the university’s history.

There is little doubt that the committee and their representatives do strongly care about other forms of inequality. The E&D Committee have a brief which includes all forms of discrimination, including ethnicity, sexuality, gender identity and disability, but while evidence of their history as a gender-equality based group is clear, there is less of an emphasis on providing support to other minority groups, who are often similarly underrepresented in the university. While the committee does include a diverse range of representatives, more focus and active support for individuals may be needed in the future regarding other harmful discriminatory factors as well as gender.

Julie Boucher and Dr Scadden believe the "old boy culture" of nepotism and privilege is dead in the department. Their work sets a precedent: a new model focused on inspiring and celebrating women and other minority groups in science. However, the admissions and employment statistics make clear that, outside of this department, there is still substantial systemic prejudice towards women and other minority groups in academia, which cannot be unraveled from the fabric of the university by one departmental committee. Broader schemes, such as better university-wide childcare provisions, have been called for and require a greater level of coordination and cooperation at a university level. Hopefully, the work of individuals and departments such as this will have a wider impact on students and staff alike, contributing to a change in the culture of Cambridge, and helping to forge a better, more diverse future for the university.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026

News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 Features / Who gets to speak at the Cambridge Union?6 January 2026

Features / Who gets to speak at the Cambridge Union?6 January 2026