Book: Soumission, Michel Houellebecq

France in 2022: the Muslim Fraternity party’s leader has won the election and made a coalition pact with the Socialists

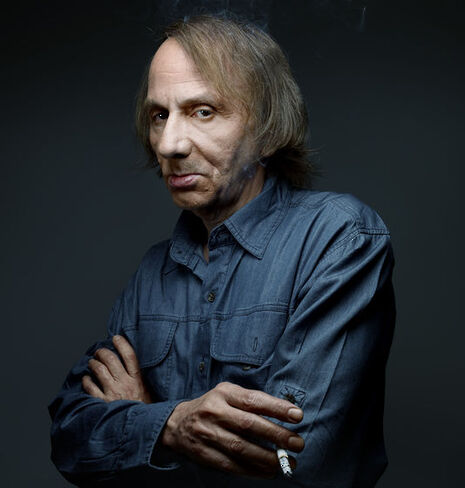

A century and a half before Michel Houellebecq’s provocative works shook public discourse in France, Paul Verlaine wrote a poem called Langueur. Its first line, “Je suis l’Empire à la fin de la décadence,” captures the bittersweet spirit of impending and complete change that is so fundamental to Houellebecq’s latest novel. In Soumission, France, or at least the Fifth French Republic, is indeed in the final stages of its downfall, but so are Houellebecq’s characters and the misanthropic literary universe of the book.

Soumission takes place in the year 2022. François, a middle-aged literature professor at the Sorbonne, feels he has reached a dead end in his intellectual and personal life. It has been years since he last made a valuable academic contribution. To chase away the ennui, he casually sleeps with his female students, one of whom, a Jewish girl called Myriam, eventually becomes his girlfriend. François believes that he is in love with her, but when she decides to emigrate to Israel under the increasing pressure of anti-Semitism in France, the only thing he truly misses about her is the quality of her fellatio. The feelings of emptiness prompted by Myriam’s departure are exacerbated by the death of his parents: François is increasingly haunted by suicidal thoughts.

The slow ruin that creeps over his personal life is set against the backdrop of a fundamental transition in French society. A moderate and skillful politician called Mohammed Ben Abbes, leader of the Muslim Fraternity party, wins the presidential election, trouncing Marine le Pen and making a coalition pact with the Socialists. He brings back palpable stability to French public life, enacts major changes to French law, campaigns for the use of green energy, privatises universities, and scraps gender equality by allowing polygamy. Ben Abbes initiates further enlargement of the European Union, which leads to the accession of Turkey and the Maghreb countries and the establishment of a new quasi-Roman Empire, with France at the helm. François adapts remarkably well to this new world and converts to Islam to secure a high-paid job in academia and two well-connected wives. The novel combines fiction with reality in an attempt to make its prophecy more realistic: François Hollande, Marine Le Pen, François Bayrou and Jean-François Copé, among others, are all characters in the book.

Soumission is arguably not about politics at all. It is an ‘end of history’ novel, describing the synthesis of Muslim and European culture as the last stage of nation-building in Europe. François, a world-renowned expert on French writer Huysmans, the high priest of 19th-century decadence, eventually embraces sweet decline in its fullness, dreamily looking forward to a future of sensual pleasure and little adversity. Despite the strong temptation to compare, François is not a 21st-century Meursault, the protagonist of Camus’s The Stranger. His encounter with meaninglessness is not profound and absolute in an existentialist sense, but rather hedonistic. Francois discovers that no higher purpose is high enough to be preferred over an easy and peaceful life.

Soumission is a stunningly pessimistic exploration of human nature and the meaninglessness of ideology in the face of multiculturalism. It describes, but does not preach, a sense of ultimate “soumission” (submission, a controversial and literal French translation of the Arabic word “Islam”) to the sweet decadence of a world where all battles have been fought, and all ideals lost.

News / Cambridge students accused of ‘gleeful’ racist hate crime4 December 2025

News / Cambridge students accused of ‘gleeful’ racist hate crime4 December 2025 News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025

News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025 News / Churchill announces June Event in place of May Ball3 December 2025

News / Churchill announces June Event in place of May Ball3 December 2025 News / Cambridge cosies up to Reform UK30 November 2025

News / Cambridge cosies up to Reform UK30 November 2025 Comment / Don’t get lost in the Bermuda Triangle of job hunting 24 November 2025

Comment / Don’t get lost in the Bermuda Triangle of job hunting 24 November 2025