Film: Ex Machina

Fiona Lin discusses gender politics, sci-fi formulae and cinematography

If nothing else, thriller Ex Machina is a brilliantly shot advertisement for the Juvet Landscape Hotel. Hidden in the grassy wilderness of Valldal, Norway, the rural retreat of software millionaire Nathan (Oscar Isaac) is replete with enough glass, concrete and wood to match his trendy beard. Complemented by the minimalist soundtrack, the film shows off the stark architecture and scenery of the setting. The visual clash between the artificial and organic is welcome – given how easy it is to be overwhelmed by Rob Hardy’s beautiful cinematography – in reminding us of the film’s overarching question of how human robots can be.

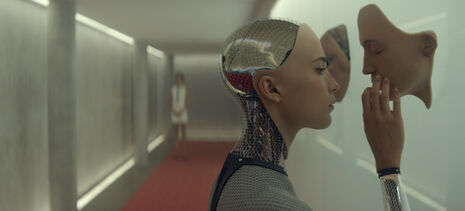

Alex Garland, as screenwriter and first-time director, chooses to explore a classic sci-fi trope, by making Nathan’s star-struck employee Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) the human component in a ‘Turing Test’ of android Ava (Alicia Vikander). The film is set over the course of a week, where Nathan interrogates and interacts with the robot – who has a cyborg body but human face – to judge if she could pass as a human or not.

Vikander’s performance as Ava is stunning, even more so than the setting. With her remarkably expressive facial range, it is sometimes difficult to remember that she is a robot, despite her visibly non-human body. Ava’s artificial physicality also has an astounding beauty to it, accentuated by the elegant walk and movements of Vikander, a classically trained ballet dancer. Furthermore, especially in comparison to the naïve yet (allegedly) brilliant computer programmer Caleb, her intelligence, however artificial it may be, is on full display. In the Turing Test sessions, it is the robot, and not the human, who displays the greater emotional perceptiveness, as Caleb is left floundering in attempts to articulate his precise responses to Ava.

Employing yet another sci-fi cliché, the relationship between Caleb and Ava becomes sexual. Ava starts flirting with Caleb, dressing in different outfits such that her robot body is practically invisible, and reversing their roles by asking him questions about his feelings. By going down this well-trodden path, it is hard for Garland to make Ex Machina stand out from similar recent films such as 2013 films Her and Under the Skin, both of which star Scarlett Johansson as the female android.

In many ways, Garland’s writing is far weaker than in Jonze’s Oscar-winning screenplay for Her. Nathan’s exposition for why he chose to imbue the robot with sexuality – because sexuality and gender are innate to humanity, and that sexuality creates the potential for pleasurable fun – is particularly clunky and unnecessarily lengthy. In choosing to write the film from Caleb’s perspective – who is less quick-witted than Nathan or Ava, and far duller, especially in the confines of a remote house – the script also feels somewhat slow-paced. Unlike Joaquin Phoenix’s protagonist in Her, Gleeson’s Caleb does not appear to have redeeming features of humour and decency.

Nevertheless, the interactions between Caleb and Ava are sufficiently well-written and well-acted to allow the viewer to believe a relationship could plausibly arise between them. Perhaps developed through their previous appearance together as the young couple Levin and Kitty in Anna Karenina, there is convincing chemistry between the pair of actors – even though for much of the film they remain separated by a pane of glass. The script of Ex Machina achieves this plausible chemistry in spite of Ava’s android form, a problem Jonze did not have to confront in making Her’s Samantha a disembodied voice.

Moreover, the script successfully crafts an atmosphere of tension in the interactions between Caleb, Nathan and mute housemaid Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno). Isaac’s Nathan, assisted by his impressive facial hair, exudes an aura of authority that leads to the satisfying anticipation of conflict when Ava begins to turn Caleb against him. If anything, the moments of social awkwardness arising between employee Caleb and employer Nathan are drawn just as ably, with a particularly funny – and also significant – moment being when Nathan and Kyoko dance in synchronicity, Caleb looking on mutely.

Garland also gets Ex Machina’s ending exactly right. Without revealing any spoilers, the action-packed conclusion affirms the film’s stridently bleak and hence uncannily realistic portrayal of how smart, and how human, artificial intelligence could be. Also, the ending goes some way to countering the misogyny inherent in the sexualisation of the attractive yet obedient female robot, something that is paralleled in the depiction of the Japanese housemaid Kyoko. However, in not engaging more profoundly with issues of gender and objectification, Garland has lost the opportunity for a fresher approach to the cliché of falling in love with a robot.

Ex Machina is a sci-fi thriller that is not only highly enjoyable to watch, but also genuinely and terrifyingly thought-provoking. With some gorgeous cinematography and Vikander’s enthralling performance, a somewhat clichéd and pedestrian plot manages to develop into a satisfying film. Overall, Garland has made a thoroughly polished directorial debut, if not a groundbreaking one.

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024

Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024 Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024

Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024