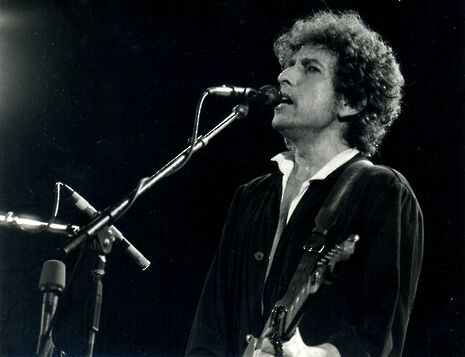

Album: The Basement Tapes, Bob Dylan

Alastair Benn takes a look at the long-awaited release of Bob Dylan’s original recordings

The release of ‘The Basement Tapes’ is a landmark in the corpus of Bob Dylan’s work, for it includes unpublished material from the original recordings. The collection defies labels. It is a surreal mish-mash of styles from blues to country. Dylan found a freedom here far removed from his personal troubles; songs like ‘Million Dollar Bash’ and ‘Too Much of Nothing’ bowl along artlessly. Their strength comes from the unique assembly of musicians. The group of hard, carefree country men, later to become known as The Band, was happy to experiment away from the frenetic public atmosphere that surrounded Dylan.

It is fitting that ‘Bob Dylan’ is a pseudonym. Various ‘Dylans’ have been constructed both by his audiences and by the man himself: the Right characterised him as subversive, while the Left embraced him as their own. He was called a ‘spokesman for a generation,’ a ‘prophet,’ and yet he repudiated all political allegiance and maintained that he was simply “a folk musician who gazed into the grey mist.”

‘One Too Many Mornings,’ an early song, reflects on the ache of worn out love and marks a particularly powerful moment in the album. One verse lilts: “From the crossroads of my doorstep/My eyes they start to fade/As I turn my head back to the room/ Where my love and I have laid/An’ I gaze back to the street, the sidewalk and the sign/And I’m one too many mornings/An’ a thousand miles behind.”

The guitar drifts as the harmonica draws out long lines overhead but his voice sparks and shatters, simultaneously retaining melancholic power. The mundane solidity of “street,” “sidewalk” and “sign” thuds into the fading of love, the death of the past, and all it held.

However, his recording rams up the backing, giving it a heavy sound and frames the clear melody with musical soup. It sounds forced, thus losing some of its original power. This failure highlights the triumph and tragedy of Bob Dylan; he could never again produce the work of the early sixties.

At the heart of our struggle is the conflict of control and chaos. Control is created by a series of complex artifices that convey different images to the viewer and to one’s own heart, all fragile in their own right but when collected and arranged over each other, secure. Folk music is such an artifice. It gives the impression of certain order in the chaos of life, a sense of belonging to the past, roots and ties that bind beyond the individual.

In folk songs, the human spirit burns bright, singing of wars, struggles, love lost, love discovered, the love that lasts a lifetime. The campfire, the singer – these are significant symbols in our imagination. Recurring reference to travelling may be to do with the search for transcendence, for our true home. These efforts portray a Dylan closer to that road with their easy freedom and unforced tone.

These tracks lack some of the resonance of Bob Dylan’s earlier work.They are not songs that fire the spirit. However, though they bite less deeply they do, perhaps, bear the mark of a happier man.

Dylan had to retreat into a basement shut off from the world to rediscover freedom in his heart. These are pretty, joyful recordings that are well worth a listen.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / Corpus FemSoc no longer named after man6 February 2026

News / Corpus FemSoc no longer named after man6 February 2026