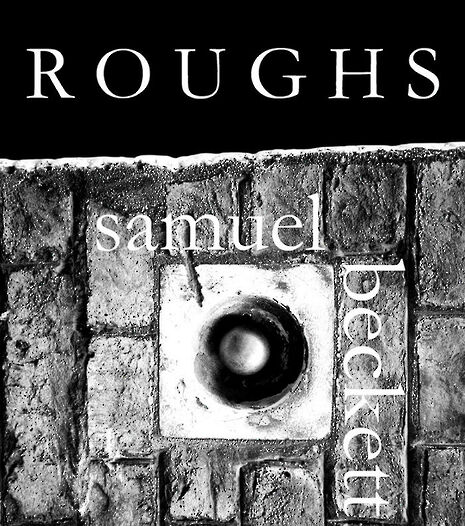

Theatre: Roughs

Rebekah-Miron Clayton attends the first UK production of an unusual pair of plays

Tristram Fane Saunders made no compromises in his pursuit to communicate the ambiguity of Samuel Beckett’s Roughs in his directorial debut. Throughout the evening the audience were purposefully kept in the dark, at times quite literally blindfolded, at others left to make their own interpretations and draw their own conclusions. This may be a vital component of any piece of Beckett, but it is especially so for Roughs, which was originally written for radio. In order to embrace the complete experience of this production it should be entered without preconceptions or prior knowledge: if you plan to see it, stop reading here.

Arriving at St John’s Chop House, we were greeted in silence by sinister, corpse-like concierge types with taped-over mouths. We were led to the play’s secret location in silence where, after nervously speculating on what awaited us, we were taken upstairs and separated from those we arrived with to be blindfolded and led into the performance space.

Rough for Radio I prompted unquenchable curiosity in the audience, reflecting the theme of the constraining nature of our pursuit of knowledge. “Tomorrow, who knows, we may be free”. The voice of ‘He’, read by Luke Sumner – an incredibly flexible and effective vocal presence – was disconcerting at first in its chilling coldness, and then transformed incredibly into vulnerability as ‘He’ grew frantic and emphatically human. The ‘Voice’ singing in this short piece was melancholically haunting, and shivers emanated through the audience.

The longer piece of the two, Rough for Radio II, offered more for the audience to grab a hold of and find some tangible meaning within. The beaten and bruised voice of Fox, read by Ben Hawkins, was ineluctably tragic: despite the obtuse nature of the dialogue within the play, it broke through as gut-wrenchingly human.

The pre-performance set up was immensely effective. Blindfolded audience members began to imagine the space they were seated in during the production, only to have their imaginings dashed after it was done. After the audience nervously removed their blindfolds, they found themselves seemingly abandoned in a near stark room with no sign of any actors or production team – just a few strategically placed radios. Dreamlike, as though it had never happened.

Perhaps the production will appeal most to those in favour of experimental theatre, theatre that has deeper imperatives than to serve simply as an entertainment facility. But the whole production team is to be applauded for successfully tackling such a strange and challenging pair of Beckett’s pieces.

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024

Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024 Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024

Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024