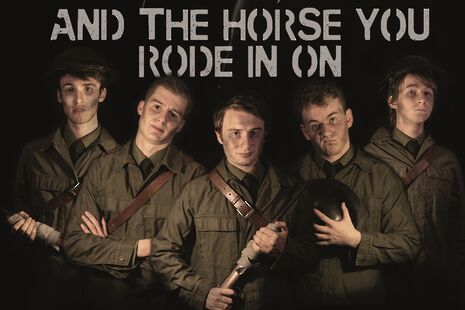

Theatre: And The Horse You Rode In On

Anne O’Neill is thoroughly impressed by this new piece of student writing which confronts the horror and poignancy of war

“Real war is where men become enemies and protectors persecutors.” And The Horse You Rode In On is a thought-provoking and affecting piece of original student writing by Tom Stuchfield. The strength of the piece lies in the poignancy of focusing on small human moments in the midst of the all-encompassing horror of war. Stuchfield is interested in portraying the words and actions of men in the most incomprehensible and inhumane of situations, as they struggle not to lose themselves to the brutality and ever-present terror of war.

It is a moving and absorbing ensemble performance, with all of the actors working seamlessly and effortlessly together. Of particular note are performances by Charlie Merriman as Shy and Chris Born as Volker. Although he appears on stage for a small amount of time, Ed Elcock’s depiction of the boyish, endearingly gauche Dixon stays with you long after the play has ended. It is in his portrayal of these innocent, vulnerable young men that Stuchfield’s characterisation really shines. Their fragility and the protectiveness they inspire in the men around them speaks most powerfully in admonishment of the act of war.

The staging of the piece is a superb recreation of a WWI dugout using canvas, sandbags and strips of wood. Dirt scattered on the floor and rough wooden stools add to the air of barely civilised existence. This overall effect is aided by excellent use of lighting to enhance the dim and hazy claustrophobia of the setting. Music, similarly, is used sparingly but to great effect, being just enough to enhance but not intrude upon the performance; the closing song is cinematically rousing and evocative.

My only qualm about the piece concerns the portrayal of the cruelty in the German dugout as contrasted with the boyish camaraderie of its English counterpart. Sam Sloman as Meinhard appeared to be channelling an SAS officer a little too zealously, and I couldn’t help but feel uneasy at the stereotypical depiction of an austere, violent German camp where order rules supreme. There is an anti-authority subtext to this play, as one watches a British commanding officer rage at the “unholy waste of resources” and realises that he is talking about the men who have lost their lives going over the top. This, in and of itself, is historically justified, but the piece would have been stronger if Stuchfield had chosen to write a less typical representation of the German commanding officers.

The weaknesses of the second scene are redeemed in the powerful final act of the play when a wounded Volker and English Corporal Spencer are isolated together on the battlefield, while the sounds of war rage around them. It is a brief moment of intimacy amid chaos and death, where each man strips away the nationalism and fervour of his military training to see the human being behind his supposed enemy. The ending to the play is disorientating, disconcerting and troubling: in short, precisely the emotions one should feel when confronted with war.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / SU stops offering student discounts8 January 2026

News / SU stops offering student discounts8 January 2026 Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026

Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026 News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026

News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025