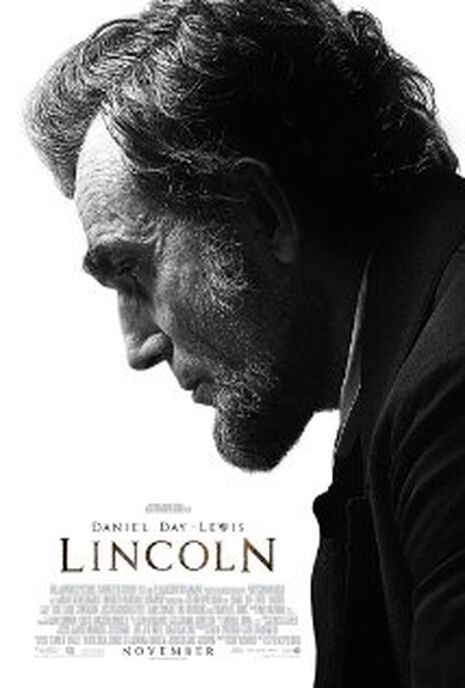

Film: Lincoln

Jim Ross raves about the plaudit-bothering new film from Spielberg and Day-Lewis

You could be forgiven for thinking that a Hollywood biopic of America’s 16th and, arguably, most revered President could result in a rather fawning affair. Factor in as director Steven Spielberg, a man who, for all his masterful command of the art form, has been prone to over-sentimentality, and apprehension from a British audience would be understandable.

However, Lincoln is a superb piece of cinema that is notable for the great lengths it goes to in avoiding a clichéd portrayal of Honest Abe. The setting is 1864 and the period after Lincoln’s re-election while the US Civil War rages. The film chronicles the attempts of Lincoln to pass the 13th Amendment outlawing slavery. Naturally, this proves a difficult task, and the President must muster all of his political skill–both above-board and otherwise– to have the law passed.

At the core of the film is a truly outstanding performance from the peerless Daniel Day-Lewis. As with much of the rest of the film, his performance eschews cliché. The voice is not one we are used to. It is thin and almost frail, though always captivating. The giant Lincoln is shown as a man who perhaps once was physically intimidating but has been wearied by age, politics and war. This is not the idealised version of the man or a $5 bill caricature.

Although this incarnation of Lincoln is shown to have a moral core, his reasons for pursuing the 13th Amendment stem from a desire to better his country, which is, for him, a political necessity. Tony Kushner’s script reveals a skilled political pragmatist, rather than a moral crusader. In addition, the script also goes to lengths to avoid well-worn traits associated with the prominent historical figure, even lightly satirising them at stages.

One Lincoln aide just about loses his cool when he feels the President is gearing up “to tell another story”, and the words of the Gettysburg address are uttered at the film’s outset, but not by Lincoln himself. Even the–possibly unnecessary, it must be said –inclusion of the assassination is presented in a fashion that is unexpected.

As with most Spielberg films, the technical craft of the picture is stunning. Excellent cinematography is backed up with a director with the experience to make a compelling picture, even in this more restrained addition to his oeuvre. Much like David Fincher’s The Social Network, Lincoln is a film depicting folk talking in rooms about procedural details, but it is utterly engrossing and riveting. Compare this engaging drama with the similarly-themed, but deathly dull, The Conspirator, directed by Robert Redford in 2011. Credit must go to Spielberg and screenwriter Kushner.

In 1838 Abraham Lincoln said: “Towering genius disdains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored. It sees no distinction in adding story to story, upon the monuments of fame, erected to the memory of others.” Whether Lincoln is “towering genius” is up to the individual viewer, but it certainly disdains the beaten path.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025