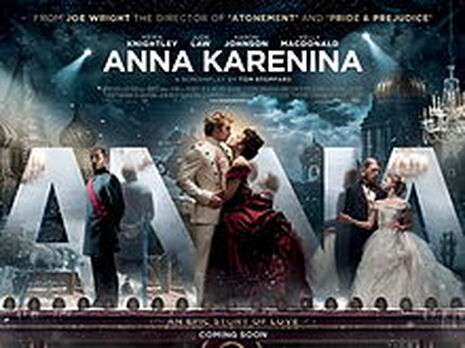

Film: Anna Karenina

Anna Rowan feels that this cinematic adaptation of Tolstoy’s novel lacks depth of character and emotion.

As I wandered into a screening of Anna Karenina clutching my £8.50 Odeon cinema ticket and an almost equally expensive bucket of popcorn, it never occurred to me that not having read the book might be an issue. The film is showing in cinema chain giants across the country and I assume that not every Anna Karenina viewer is also a seasoned Tolstoy reader. Besides this, it is not being marketed to some kind of intellectual niche but rather to a mainstream audience in the vein of Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice and Atonement. Unlike these adaptations, Anna Karenina struggles to stand on its own as a film without previous knowledge of the book in a way that makes it unenjoyable for many of its viewers.

Before seeing the film, I thought of Anna Karenina as a kind of Russian Madame Bovary. Adultery aside, I was expecting genuine character complexity of the kind that is lacking in many current films because it allows characters to be unlikeable without being branded as ‘the bad guy.’ However, Joe Wright’s adaptation featured a character whose complexity was undermined by an inadvertent sense of character inconsistency.

At the beginning of the film, Anna Karenina’s characterisation is little more than a plot springboard. We are sold on her intensely fashionable and, somewhat by extension, socially-respectable attributes but her character falls flat beyond the costume and sociability. Kiera Knightly just doesn’t do ‘maternal’ very well and her stilted relationship with her son (resembling sibling affection only with more head stroking) detracts from a complex aspect of her family-orientated nature. While her maternal love could have contrasted with her obligation to a cold and conservative husband, it instead fails to alleviate the negativity of her home life. The result is a family life which appears too one-dimensional to be character building.

This isn’t just down to a blip in Kiera Knightly’s acting since she is otherwise commendable in the film. Although the complexity of their marriage is beautifully acted, our lack of screen time with Anna and Karenin as a couple before her affair is also a contributing factor. We just don’t see enough of it before Vronsky’s unblinking blue eyes tell us where this story is headed. This frames their marriage as a plausible prelude to adultery but is unconvincing as a pivotal component of Anna Karenina’s character development. We see their marriage more as a phase in Anna Karenina’s life than a genuine influence on her character.

Why is this important? Because this initial light characterisation of Anna Karenina jars with the emphasis on her complexity in the second half of the film, making it both perplexing and unemotive. Her character becomes riddled with unpredictability after the birth of her daughter and increasingly verges on insanity. But while this erratic state is no doubt understandable, Anna Karenina’s emotional see-sawing goes only too well with our founding view of her character as changeable rather than complex. We dismiss her family life as a mere backdrop to adultery and miss her grounding as a woman already living in an entanglement of maternal love, social expectation and marital duty. Anna Karenina doesn’t become conflicted. She is always conflicted. But as this aspect of her character doesn’t come through, melding a character who is very much secondary to the plot with a character whose complexity later governs the plot just doesn’t work. Anna Karenina’s emotional instability doesn’t make her look complicated. It just contributes to her character inconsistency.

This is not to suggest that every cinema-goer who watches Anna Karenina without having read the book beforehand will read this much into the film. But I do believe that this flaw in Anna Karenina’s characterisation critically detracts from the emotional impact of the film for many. Perhaps if you are already familiar with the characters and storyline, you can fill in the character gaps that this adaptation leaves open. To me, however, this film felt like an uneven attempt at juggling hundreds of pages worth of characterisation and plot that loses its main character in the process.

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025 News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025

News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025 News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025

News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025 Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025

Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025 Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025

Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025