Review: Grace – Esther Morgan

Emma Greensmith enjoys a few moments of stillness

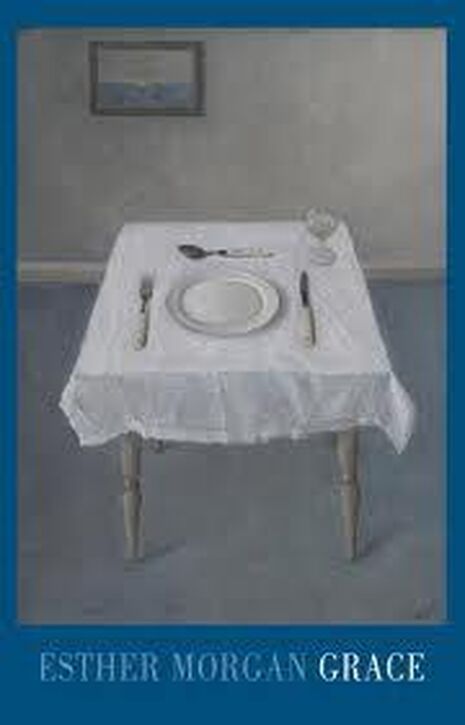

Esther Morgan’s third collection, shortlisted for the T.S Eliot prize for poetry, will not suit all palates. Centred on what the poet calls, “our desire for revelation and the difficulties of learning to watch and wait” the collection itself becomes an exercise in watching and waiting, a subtle assault on the kinetic. Through portraits of people poised “on the edge of a moment”, but never actually in it, Morgan asks how we cope with this potentiality, “waiting without hunger in the near dark/for what you may be about to receive”. Some can’t cope with it at all: one critic compares reading Grace to “watching a dull art film in which the promise of a jolting denouement never comes”.

Yet this very inaction is what gives the poems their force. They compel because they confront people, places and times that seem to amount to nothing, daring us to see meaning in the meaningless. The title poem evokes with elegant simplicity the opportunities to be found in empty moments, “In the stillness, everything becomes itself”. ‘The Dew Artist’ movingly confronts uninhabited time, the gulf between thought and action; “Perhaps it’s enough that someone thought of it: / of rising in the gap between night workers coming home/ and the first dawn commuters”. And ‘This Morning’ explores the significance, or insignificance – it’s up to us – of the simple sight of “the sun moving round the kitchen” using perhaps the most beautiful analogy in the collection: “the light moved on,/letting go each chair and coffee cup without regret// the way my grandmother, in her final year received me:/ neither surprised by my presence, nor distressed by my leaving,/ content, though, while I was there”. As with the experience of watching a good art film, we feel constantly on the cusp of something, exhilarated without fully understanding why.

Throughout the collection, the reader experiences Morgan treading a thin line, the poet herself “on the edge”. There is a strong religiosity to the poems, expressed both overtly- “angels and infants/robes and raiment/a haloed revelation” and allusively in the recurring imagery of bread and light. Yet Morgan takes great pains to avoid slipping into portentousness with a deliberate lack of detail and unadorned language. Holy but not ominous, simple but not plain, unspecific but not vague: we may occasionally feel that her efforts to find the balance are rather forced, but in the end she pulls it off.

Admittedly, some poems achieve this effect better than others. Tellingly, it is in her attempts to come closer to depicting solid action, for instance in Five Easy Pieces or the strangely ineffective ‘News’, that Morgan falls flat. Thankfully, though, such misfires are few and far between, dwarfed by the achievement of others such as ‘Harvest’, ‘Garbo Among Us’, and the poignantly sad I want to go back to the Angel. This is overall a highly successful collection, which challenges us to revel in facing what makes us most uncomfortable, drawing the reader in with words that are “simple, though not easy”, with insight and, yes, with grace.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026

Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026 Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026

Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026 News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026

News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026