Literature: Alfred Jarry – A Pataphysical Life by Alastair Brotchie

Charlotte Keith on the biography of the French, eccentric, avent-garde writer Alfred Jarry

Pataphysics: the science of imaginary solutions. Variously understood as a pun (in the French) on ‘leg of physics’, ‘not your physics’, ‘physics pastry’. The inventor of this surprisingly influential pseudoscience was Alfred Jarry, a French writer who died in 1907 aged 34, and whose work is considered the foundation of the later absurdist theatre of Beckett and Ionesco. He liked to refer to himself using the royal ‘we’ – a trait adopted from the anti-hero of his most famous play, Ubu Roi – eat meals in reverse order, let his pet owls defecate on the floor, and was terrified of drinking water.

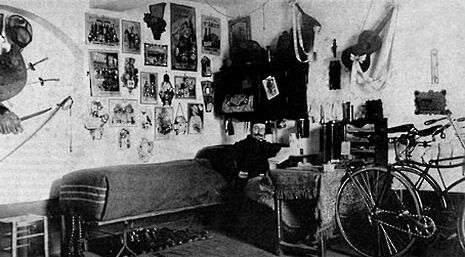

In this, the first full-length critical biography of Jarry published in English, Alastair Brotchie brilliantly evokes the avant-garde artistic movements of fin-de-siecle Paris in all their glittering grubbiness. The literary salons, the prodigious feats of drinking, the creative collaborations and conflicting ‘isms’ of the various members of Jarry’s circle – Mallarme, Gide, and Picasso among them – are rendered vivid and concrete. The book is gorgeously illustrated; photos, drawings, and facsimiles of letters and manuscripts abound.

Jarry’s life, from provincial schoolboy beginnings to Parisian eccentricity, literary renown (and indeed infamy) are extensively chronicled, using a variety of sources, notably anecdotes taken from the memoirs of his literary acquaintances. The chapters alternate between biography and cultural analysis – a combination that works well, although more of the latter would have been welcome. The most compelling part of the book is the final chapter dealing with Jarry’s protracted illness, aggravated by heavy drug and alcohol use. In a chilling moment, Brotchie lets Jarry effectively narrate his own demise by quoting from his unfinished final novel La Dragonne:

"He began, simply but furiously to drink…And he drank the very essence of the tree of science at 80 degrees proof, the spirit that retains the taste of the apple, and he felt at home in Paradise regained".

The only real problem with this book is a lack of fidelity to its subtitle – ‘a pataphysical life’. Conventional biography is pursued at the expense of a more whimsical approach that might have better suited such a mercurial subject. Brotchie frets about the impossibility of recovering definite facts in the life of this enigmatic figure, even as he attempts to record in – sometimes tedious – detail, the financial aspects, say, of Jarry’s literary career. At times,however, an over-simplistic equation of Jarry himself with the protagonists of his works threatens to reduce the literature to self-dramatization writ large. Jarry played complex games of selfhood, incorporating elements of his characters into his persona. But these were frequently tongue-in-cheek – a game played with the ‘audience’ present, and Brotchie is good at calling Jarry’s bluff, suggesting moments at which he may have lost control over the line between himself and Ubu.

But, as Jarry’s close friend and editor, the novelist Marguerite Rachilde, wrote ‘he wanted his life to conform to his literary paradigm’. Brotchie’s reading of Jarry’s life, his forming of events into a cohesive, rational narrative, repudiates this. By focusing so much on factual reconstruction, Brotchie risks forgetting that for Jarry, life was a kind of literature, and should be ‘read’ as such. On a pataphysical view, the imaginary and the actual are equally real: Jarry’s imaginative world would benefit from being considered more ‘real’ by Brotchie.

It would be unfair to condemn this book on the grounds that it is too sober, inadequately absinthe-soaked, to do Jarry justice. But his irrepressible whimsy remains somehow elsewhere, confounding the reductive tendencies of Brotchie’s biographical account. You almost get the sense that Jarry himself is standing at a distance from the book, making pronouncements like ‘perception is only a hallucination that is true’, and quietly smirking. Towards the end of the book, Brotchie acknowledges the limits of this biography: the ‘final act’ of Jarry’s life, we are told, ‘resists overly interpretative readings’. For all his efforts, Brotchie has not been able to entirely pin his subject down – which is no bad thing. Jarry remains tantalizingly mysterious; bizarre and fascinating.

In typical Ubuesque fashion, Jarry once claimed ‘we believe, that the applause of silence is the only kind that counts’. But someone who radicalized theatrical tradition to the extent that he did undoubtedly deserves something more than silent applause – despite its flaws, this biography ensures that Jarry receives that.

News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026

News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026 Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026

Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026 News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026 Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026

Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026