Event: Pinholes and Portraits

Simply put, ‘Pinholes and Portraits’ was a visual delight. This collaboration between the photographer Mark Woods-Nun and FLACK, a charitable social enterprise which works with homeless people, was perhaps unexpected, but the results are well worth seeing. FLACK’s attachment of beer-cans to assorted lamp-posts is not another example of misguided modern art. A thin sheet of photographic paper was placed in each can, exposed to the world by only a tiny pin-hole, silently and vulnerably capturing an image.

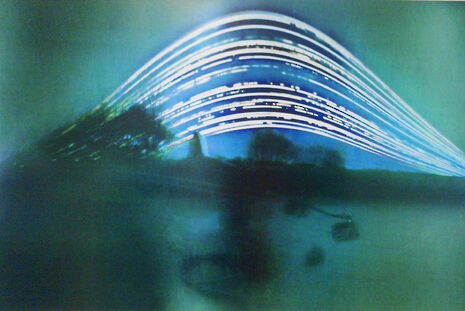

Taking a minimum of 3 months to develop, the images come with high expectations, and they do not disappoint. The surreal, euphoric results possess a dream like quality which captures the passing of time with honest simplicity. The remnants of the sun, seen as streaks of textured light, across often the most ordinary of settings, have an ethereal quality, the slightly out-of-focus centre-pieces contrasting with the clear background. The creation of the beautiful from the mundane is especially evident in ‘Car Park’. The images challenge the idea of sun’s path being an inevitable part of life, as these depictions of the winter equinox celebrate the sun’s movement in contrast to the static normality of our surroundings.

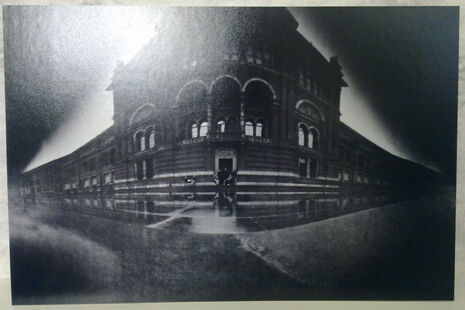

Although the use of beer-cans could be written off as the result of limited funds fundamentally limiting the potential of the final image, the inverse is true. The selection of photographs from FLACK’s visit to the V&A demonstrate the superiority of an image produced using this method to that of a digital camera. The far wider landscape captured, and the texture it brings to the view adds a drama and poignancy that the digital equivalent could not rival.

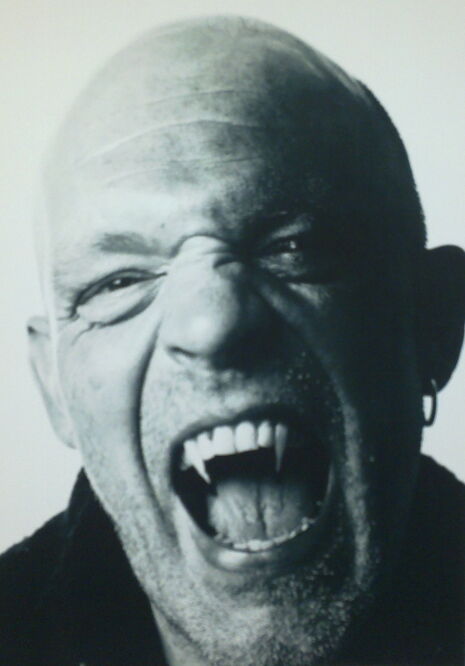

This exhibition continues to challenge assumptions by eloquently ridiculing stereotypes. Nowhere is this more evident than in the materials used to make the ‘cameras’. When thinking about homeless people and beer, negative connotations can’t help but arise in your mind. However, this project offers a challenge to this way of thinking, shown by the positive atmosphere of the opening night and its appeal to a wide section of the Cambridge community, ranging from the average student photography geek to intrigued residents of Chesterton and finally to the artists themselves. The studio-shot section also conveyed this by portraying “images of real people not homeless stereotypes” as FLACK’s creative director Kirsten Laver rightly describes the ‘Pimped Portraits’. Despite the distasteful name, (the only criticism of this event I can offer), the photographs are moving. Although the shots themselves are eye-catching enough, it is the smile-provoking additions by the subjects that make them memorable. These range from those who chose to express their roots by superimposing their hometown into their portrait, to the photo-shopping of fangs for humorous effect, giving a hearty chuckle a devilish glare, such as the playfully named ‘Can I borrow a cup of sugar please?’

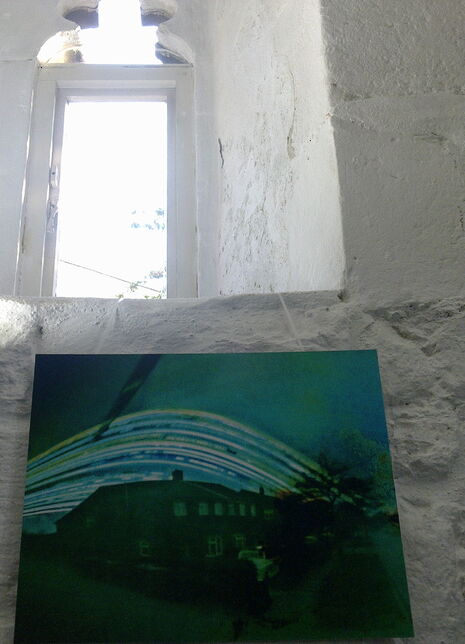

Another highlight of the exhibition was the setting. The Chesterton Tower was not just an inanimate vessel in which the photographs were displayed; it almost formed part of the exhibition itself. In part this was due to its good acoustics, complimenting the circulatory, intriguing sounds of Toby Peters’ guitar. Mostly, though, it was how in tune the ethos of the exhibition was with the building’s relation to the present that struck me. Although almost 700 years old, the Tower is a vibrant space, an inspiring reinvention of the past which creates something for the future’s use. This was similar to how the exhibition sought to take things considered old, obsolete even, like the empty beer-cans and the ancient photographic process, and reinvent them so that they created new art in the present, and hope for the future of FLACK.

However, I don’t intend to suggest the exhibition is without precedent, in fact it is to its credit that it has parallels with the big shots. The Victoria and Albert from October to February showed an exhibition on the development of camera-less photography, and only this April Tate Modern Film celebrated the camera-less creation of Jose Antonio Sistagia, ‘...ere erera baleibu izik subua aruaren...’. His technique of painting straight onto film was similar to FLACK’s foray into using photographic chemicals as paint in the series of Chemigrams. In fact, the Chemigrams themselves worked to reiterate the relevance of the exhibition, as their use as the basis of Toby Peters’ ceiling projections echoed the stunning visual effects used at the most fashionable night of the Cambridge calendar: the arcsoc party.

Worth the cycle or extended stroll to Chesterton tower, for curiosity’s sake.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026