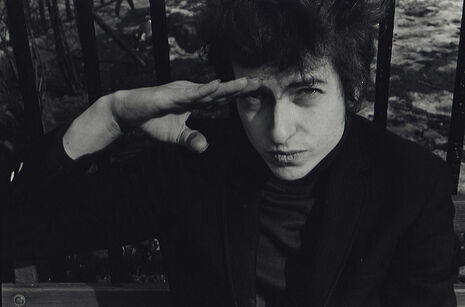

Album: Bob Dylan – Fallen Angels

Dylan’s 37th album is a sincere and enjoyable release, with sumptuous arrangements and captivating vocal performances

Just a little over a year since his Frank Sinatra covers album, Shadows in the Night, came out, Bob Dylan is delving back into the Great American Songbook again with this his latest release, Fallen Angels. Recorded during the same sessions as Shadows in the Night, it should come as no surprise, then, that Fallen Angels retains many of the characteristics which made its predecessor such a pleasing and rewarding listen.

Again, Dylan’s wizened croon is perfectly complemented by his backing band. Melancholy pedal steels slide and shimmer over the top of demure double-bass lines and laid back, swinging drum grooves. On the only real fast number, ‘That Old Black Magic’, jazzy guitars dance effortlessly through the chord shapes and scamper up and down the scales, injecting vigour and a welcome change of pace into the otherwise-easy-going track list. Always, though, the songs are sweet to the ear. The residual, and narrow-minded, criticism of Dylan throughout his career has been that he cannot sing – a criticism that has only intensified as he has grown older. When Dylan reintroduced himself to the world in 1997 with the stellar Time Out of Mind, the effect the Never Ending Tour had had on his voice became apparent. Bereft of its sixties’ shrillness, the voice was now deeper, gruffer, raspier. Over the past twenty years, however, Dylan has learnt to live with his limitations and even use them to his advantage. Replacing the silky smooth tones of Ol’ Blue Eyes with the world-weariness of a septuagenarian actually gives these well-known songs a new and poignant resonance. In light of the recent deaths of some of music’s greats, one cannot help but be aware of a pervading sense of mortality throughout the record.

But, equally, there is a childish enthusiasm to Dylan’s deliveries. Certainly, one has to admire his ambition when he goes to reach the high notes in a song like ‘Polka Dots and Moonbeams’. It is really quite charming. And, however large and unlikely the leap, he usually manages to pull it off, too. Dylan may be at full strain most of the time, but that is not to the album’s detriment. Rather, it demonstrates just how much Dylan cares about what he is singing. These are not throwaway covers, but loving renditions and adaptations of songs Dylan has obviously cherished since childhood. ‘Skylark’ – the only track not to be recorded by Sinatra – is perhaps the most joyous of the lot. A bright, ebullient fiddle lends the track a country flavour and acts as a foil to Dylan’s gruffness, highlighting the comic apposition between the airy and avian lyrical theme and the singer’s throaty rasps. In fact, there is often a tinge of irony to the singing. Dylan’s timing and intonation – always impeccable in their nonchalance – are employed to particular comic effect on the opener, ‘Young at Heart’. That Dylan is only too aware of the irony of his singing this ode to youthfulness is apparent in his tired and cynical delivery of the line ‘Life gets more exciting with each passing day’. By contrast, ‘All or Nothing at All’ is a moody and menacing departure from the sunny Sinatra version and sees Dylan practically growling the titular ultimatum he sets before his beloved.

Blonde on Blonde, arguably Dylan’s greatest work, may have turned fifty years old, but Fallen Angels proves that Bob still has something to say. Of course, the album does not come close to his sixties’ heights, but that is not Dylan’s intention at this point in his career. On Fallen Angels, like on Shadows in the Night before it, Dylan sings with no political or personal agenda, but purely out of a respect for his forbearers and a love for his craft. These sentiments translate across to the album’s sumptuous arrangements and captivating vocal performances, and they are what make this such a sincere and enjoyable release.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Supporters protest potential vet school closure22 February 2026

News / Supporters protest potential vet school closure22 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 Comment / A tongue-in-cheek petition for gowned exams at Cambridge 21 February 2026

Comment / A tongue-in-cheek petition for gowned exams at Cambridge 21 February 2026